A Fix for Chronic Transit Funding Shortfalls Could Be Up To the Voters This Fall

1:21 PM EDT on April 1, 2022

The WRTA’s downtown bus hub, next to Worcester’s Union Station.

It's become an annual rite of spring: transit agencies across Massachusetts are examining blooms of red ink in their budgets for the next fiscal year, and wondering whether state lawmakers will step in and give them the funding they need to avoid service cuts.

This year, though, voters may be able to take matters into their own hands when they vote in November on the "Fair Share Amendment," a constitutional amendment that would increase the tax rate on residents who earn more than $1 million a year, and devote the new revenue to public education and to transportation infrastructure.

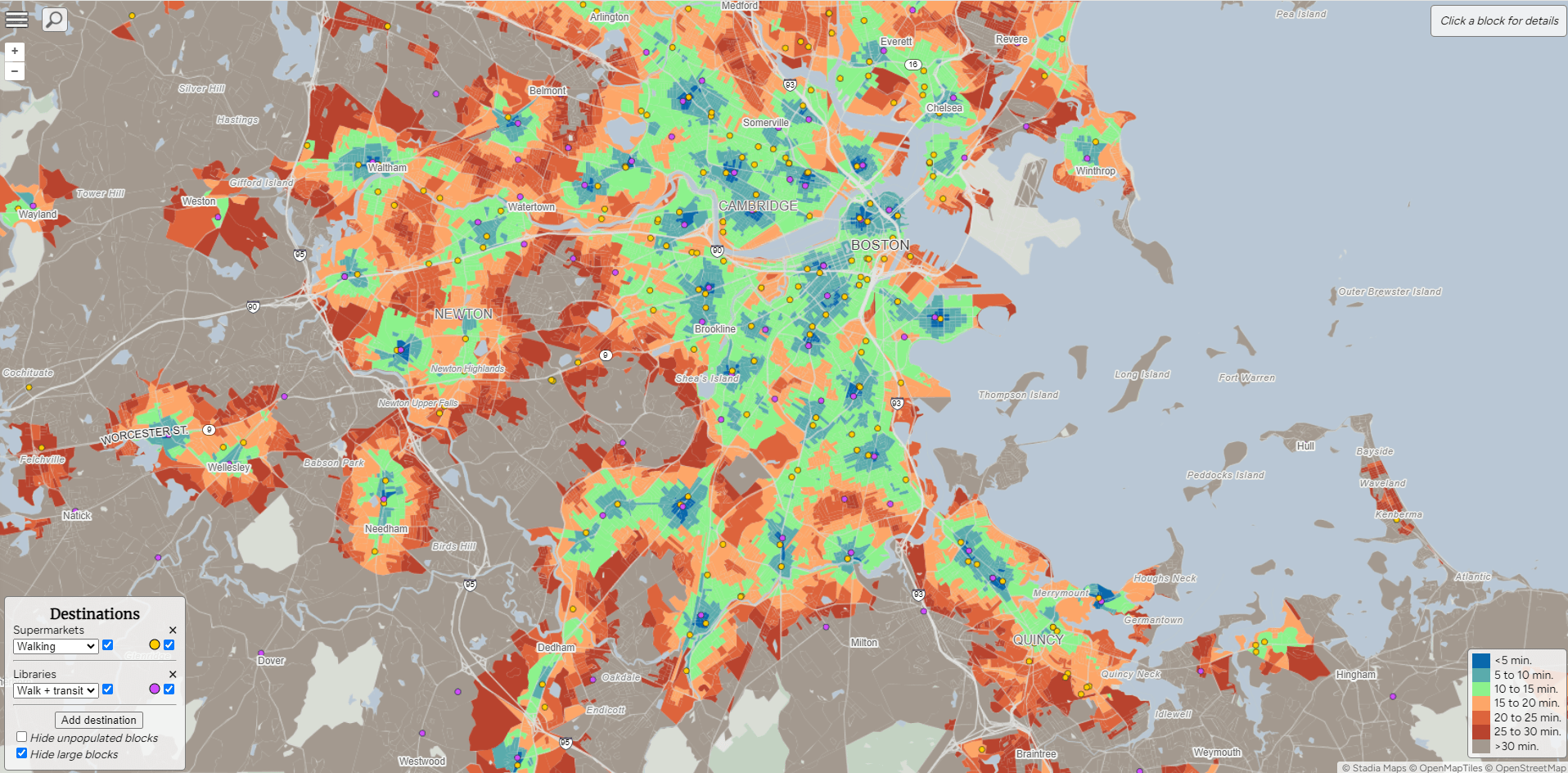

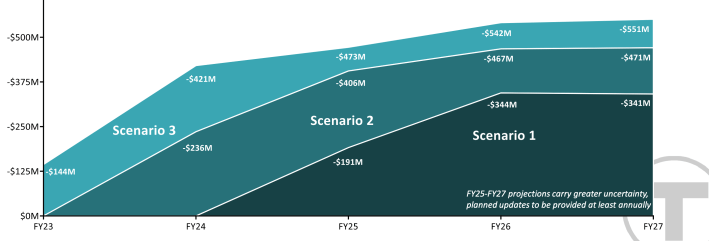

At its March meeting, the new MBTA board of directors got a preview of the agency's fiscal year 2023 budget, which will take effect on July 1. While one-time pandemic relief funds will help the agency balance its budget for now, the T's Chief Financial Officer, Mary Ann O'Hara, warned board members of a "fiscal cliff" coming when federal relief funds run out (in the chart below, "scenario one" assumes that riders return to the T relatively quickly, while the more pessimistic "scenario three" assumes a sustained long-term reduction in public transit ridership):

Future budget uncertainty also limits how ambitious the MBTA can be in its 5-year Capital Investment Plan, its budget for long-range transit expansions and major maintenance projects.

Last September, the Massachusetts Taxpayers Foundation warned that the T would need about $25 billion over the next decade just to maintain its existing system. Right now, only about half of that amount has been actually committed from state and federal sources, and even more funding would be needed to build upgrades like the Red-Blue Connector and the electrification of the regional rail network.

Transit budget deficits existed long before the pandemic, too: between 2016 and 2020, the Legislature regularly appropriated over $127 to $155 million a year in "additional state assistance" to help balance the T's budgets. And a lack of reliable state funding also afflicts the state's Regional Transit Authorities (RTAs), whose financial support from the state government has been declining in recent years.

In March 2020, days before the pandemic shut down workplaces across the nation, the Massachusetts House of Representatives passed a major transportation funding bill that would have generated over half a billion dollars a year in additional revenue through a 5-cent gasoline tax increase, a 9-cent increase to diesel fuel taxes, hikes to the Commonwealth’s minimum corporate tax rates, and higher fees on app-based ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft.

Though that bill passed by a wide margin in the House, the pandemic quickly became a more pressing legislative matter, and the Senate never brought the bill to a vote. And this year, there's been more debate about repealing fuel taxes than there's been about raising more revenue for transit.

But voters may have an opportunity to solve these problems themselves later this year.

The Fair Share Amendment, which will be on the ballot in this November's election, would levy "an additional tax of 4 percent on that portion of annual taxable income in excess of $1 million," and specifies that the revenues can only be used "quality public education and affordable public colleges and universities, and for the repair and maintenance of roads, bridges, and public transportation."

The Fair Share Amendment is “the most significant source of potential new investment that’s on the horizon,” says " Phineas Baxandall, Senior Policy Analyst & Advocacy Director for the Massachusetts Budget & Policy Center.

If passed, the new tax rates would take effect for the 2023 tax year, which means that it could start delivering new revenues before the end of the current fiscal year.

"People who have high incomes are required to pay anticipated income taxes, which would start to come in January of 2023," says Baxandall. "You can imagine a scenario where you have the RTAs and the MBTA beginning to reckon with the end of federal pandemic relief at the same time that the first Fair Share money starts to come in."

Read More:

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter