Boston's traffic is still the worst in the U.S. – but according to the latest analysis from INRIX, the transportation data analytics company, slight improvements to Boston's transit system could have a big impact on regional congestion, and save commuters millions of hours every year.

The 2019 Global Traffic Scorecard from INRIX, released Monday morning, argues that Boston's drivers lose more time in traffic than drivers in any other U.S. city.

According to INRIX data, which is compiled from cellphones, public data, GPS units in motor vehicles and various other sources, the "typical" Boston driver squandered 149 hours (or 3.7 full-time work weeks) stuck in traffic jams in 2019.

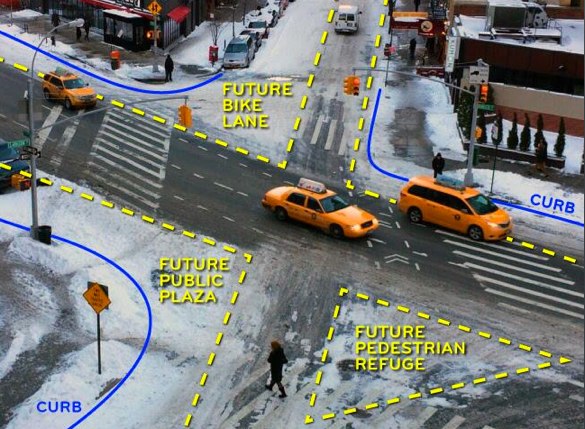

This year, for the first time, INRIX also analyzed travel times for similar trips by bike and by transit, and found that the Boston region's transit system, in particular, had a high potential for improving Boston's worst-in-the-nation ranking.

"Scorecard’s calculations are based upon the top 200 car commutes in a metro area, identified via our trips data," explained Trevor Reed, an INRIX analyst, in an email exchange with StreetsblogMASS on Monday. "We analyzed (bike and transit) travel times on these 200 routes and compared them to car times... In the case of Boston, there is a relatively small time penalty for car commuters to switch to transit, so even marginal changes could lead to major reductions in car use and corresponding benefits in terms of congestion."

Some important caveats apply to INRIX's congestion methodology. As with the Governor's "Congestion In the Commonwealth" study released last year, INRIX defines "congestion" as the difference between the time it takes to make a trip in rush hour to the amount of time it would take to make the same trip in "free-flowing" traffic.

By INRIX's definition, 10-minute, 3-mile trip on Interstate 93 is considered to be a much bigger waste of time than a 10-minute, 3-mile drive down Beacon Street through Brookline, simply because it might have been possible to make the highway trip in a third of the time if you had left in the middle of the night.

In reality, though, nobody plans their daily commute with the expectation that they'll be able to go a mile a minute on any of the Boston region's expressways. In other words, what INRIX measures as time lost in congestion may really just be an ordinary commute on a highway with an unrealistic speed limit.

Eagle-eyed congestion report readers may also note that INRIX's scorecard differs significantly from the Texas A&M University's annual "Urban Mobility Report," which also used INRIX data. That report ranked Boston #6 in congestion among the nation's cities, and concluded that Boston-area commuters lost only 80 hours a year to traffic slowdowns.

Reed explains that the Texas A&M researchers analyzed the larger Boston "urbanized area," which, as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau, includes parts of Worcester County and southern New Hampshire. For their annual scorecard, INRIX analyzes the more urban areas of the region, generally inside the 128 loop, where "congestion" (as INRIX defines it) is more common.