Student transportation is one of the largest budget expenses for the Boston Public Schools – and the expense and logistics of busing students is likely to be even more daunting this year, with increased physical distancing requirements from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fortunately, many students who traditionally take buses live within walking distance to their assigned school. Walking School Bus programs are worthwhile initiatives even in “normal” times – they reduce student transportation costs, give children physical activity, and help to strengthen school communities. But during a pandemic, these programs can also alleviate crowding on school buses and provide part-time employment jobs to parents as trained walking captains.

As a Safe Routes to School advocate and former PE teacher at the Ellis Elementary School in Roxbury, I witnessed firsthand the impacts of busing on my former students.

One of my students, a 5th grader, lived in Roxbury, and his house was just over a mile from the school, so he qualified to ride the school bus. Quadir typically left his house at 8:40 am to wait for the bus. Many mornings, the bus was delayed in traffic and wouldn’t arrive until after the first bell at 9:15, which meant he had to rush and eat his breakfast before class started at 9:30.

When school ended at 4:10 pm, Quadir waited in his bus room to go home. His family had told me that some evenings he wouldn’t arrive home until after 6 because of the rush hour traffic.

Quadir’s walk to or from school took just over 20 minutes: if he had been able to walk every day instead of taking the bus, he could have had more time to spend on homework or with his family at home, and he would have had a more reliable way to get to school on time.

Quadir joined Councilor Kim Janey and me on the Ellis 2018 Winter Walk to School Day. He was walking next to me in the front of our walking school bus that morning with a huge smile on his face. The next day, Quadir was banging on my gym door during his lunch wanting to ask me when the next walking school bus was.

Supporting walking and biking to school is an evidence-based activity to increase physical activity, which can also improve academic performance among youth like Quadir. Safe Routes to School (SRTS) is a national model to encourage safe and active transportation to school, and is one of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Hi-5 initiatives, with strong evidence that it can lead to a positive health impact within five years. The walking school bus was also highlighted in the Harvard T.H. Chan School for Public Health's Schools for Health: Risk Reduction Strategies for Reopening Schools report.

Boston is ready to implement a strategic walking school bus program. More BPS K-5 and K-8 schools are moving to a home-based assignment policy, so we will see an increase of students attending neighborhood schools, living within a school’s designated “walk zone.” Our goal should be to encourage these students to walk, instead of being dropped off by a car.

Considering Quadir and the impact it had on his school experience, I wanted to see how many other students at the Ellis live within walking distance of school, but take a bus.

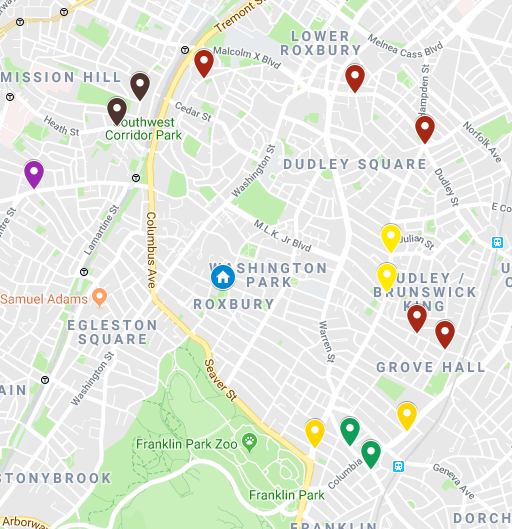

I used the 2017 Ellis Elementary morning bus list and identified all the bus stops that were a 1 to 1.25 mile walk from the Ellis (mapped below). Out of the 210 students who qualify for the bus, 139 of them (66 percent) live within 1.25 miles of the Ellis. Some of those students receive services that make a bus ride necessary, but many of them could be able to get to school faster and more reliably on foot:

What if, instead of filling multiple buses to transport these students every day (which we can’t do without breaking CDC guidelines), we provided a different service for these students?

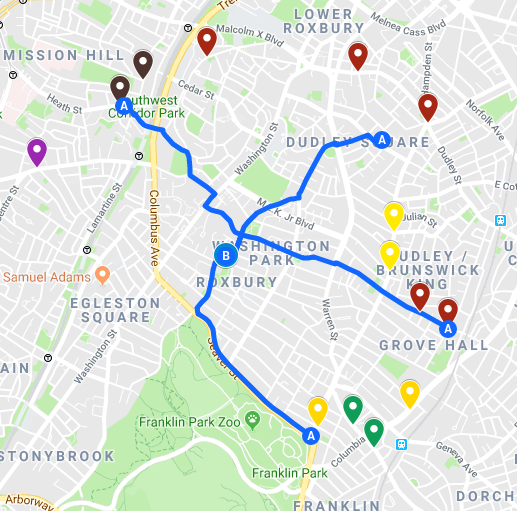

Adults specially trained in pedestrian safety could meet students in the morning and in the afternoon and lead a safe walk for students to school and back. The city could also spend some of the money it saves from fewer bus trips on quick-build improvements to sidewalks and crosswalks. A walking school bus would also benefit all the students who live inside the one-mile radius from the school:

According to a 2018 Boston Public Schools transportation budget presentation, the average annual cost to transport one student by bus is $3,000 (note that this was before COVID-19; the costs of busing students this year is likely to be much higher).

I estimate the cost of four walking school bus routes, each with three adult leaders earning $15 an hour, for the entire school year, to be about $102,600 a year.

That means that if a robust walking school bus program at Ellis could move 100 students on foot instead of by bus, the school would conservatively save about $200,000 a year – and that’s without counting other benefits like cleaner air near schools, safer neighborhood streets, and healthier students.

As teachers, we look at educating the whole child: their physical, mental, and emotional health. By creating a Walking School Bus Program program with trained walking school bus leaders, schools won’t only see lower transportation costs: we’ll also see more students enjoying the benefits of physical activity and cleaner air, arriving at school on time and ready to learn.

Sam Balto taught PE for three years at the Ellis Elementary school in Roxbury. While there Sam, started the Safe Routes to School program to support active transportation for students to school. Through advocacy efforts by Sam and the Roxbury community, the Ellis School last year was awarded the MassDOT Safe Routes to School Infrastructure Project Funding Program. Sam now lives and teaches in Portland, Oregon where he won the Weston Award for his child focused advocacy through Oregon Walks. Sam was recently a panelist for the Streets for Kids NACTO-GDCI webinar Rethinking School Streets in the Time of COVID-19.