Boston has ambitious climate goals that call for the city to cut car traffic in half by 2030, by shifting thousands of daily trips to transit and other more sustainable modes of transport.

But so far, there have been precious few examples of places where those goals have been reflected in redesigns for the city's major streets, where public space remains overwhelmingly devoted to single-occupant motor vehicles.

Now, citing those climate goals and the anticipated travel needs from large development proposals for the area, City of Boston planners and community advocates are pushing to redesign Western Avenue in Allston to a bus-priority "transitway" that would limit private vehicle traffic to just one lane for most of the street's length between Barry's Corner and the Charles River.

The idea has come out of a zoning and infrastructure study being conducted by the Boston Planning and Development Agency (BPDA) in conjunction with transit planners at the Boston Transportation Department.

The BPDA anticipates roughly 10 million square feet of new development along Western Avenue in Allston in the coming years, plus another 7 million square feet of development in surrounding neighborhoods, like the area around the new Boston Landing regional rail stop.

In order to handle all of the trips associated with those new developments, Allston's streets will need to get much more efficient at moving people and goods. The current Western Avenue, which generally features two general travel lanes, an intermittent painted bike lane, and on-street parking, is already frequently congested, which causes significant delays on the MBTA's route 86 and route 70 buses.

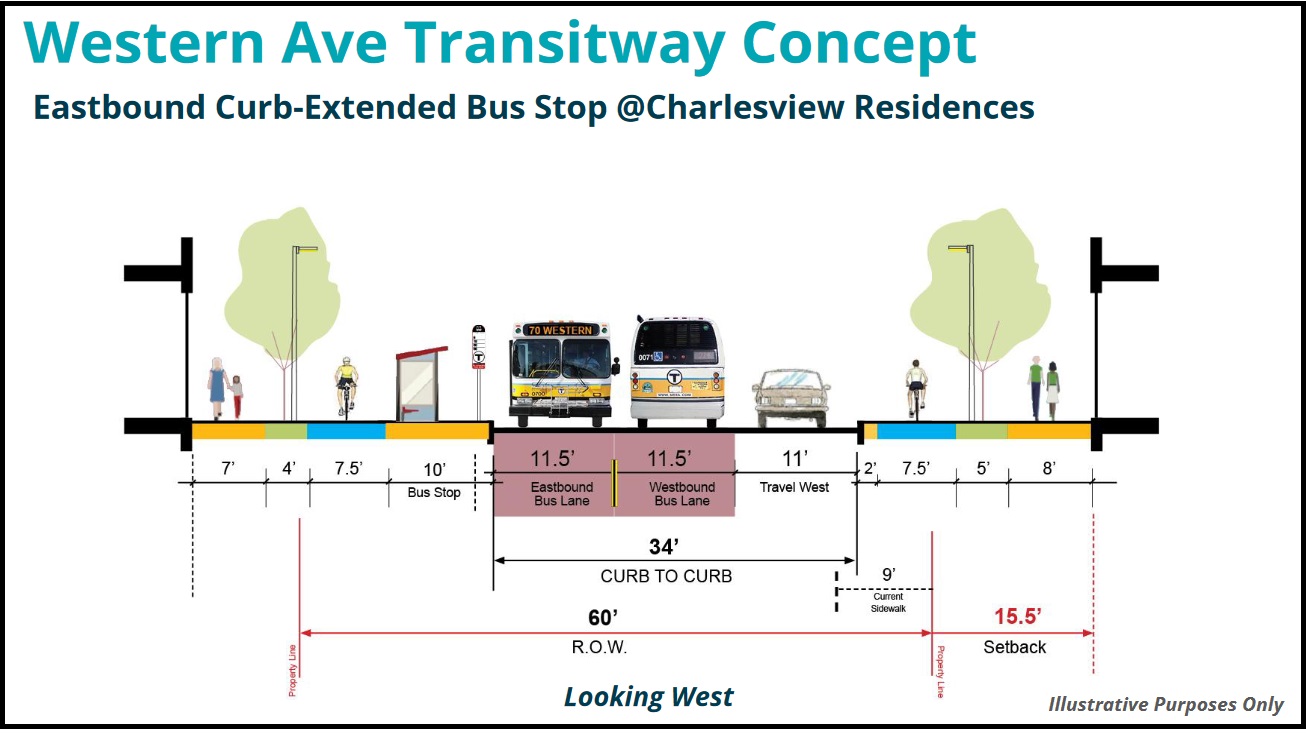

Under the city's transitway proposal, which would be phased in over the course of several years in conjunction with new development along Western Avenue, the street would be reconfigured to provide two lanes for buses and a single one-way lane for general motor vehicle traffic.

The street's curbs would also be adjusted to provide wider sidewalks, larger bus stops, and sidewalk-level bike lanes. The new street would be wider overall, but the space between curbs for motor vehicle traffic would generally be narrower.

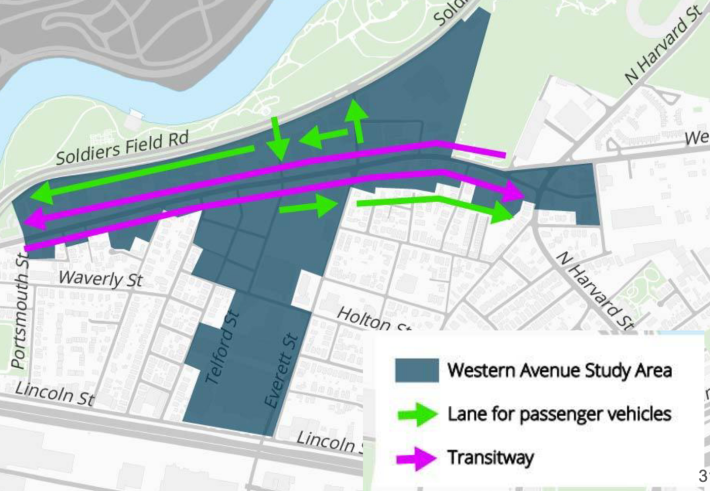

Private cars would still be allowed on Western Avenue, but they would be restricted to a single one-way lane, running eastbound only east of Everett Street, and westbound only west of Telford, with a one-block segment allowing two-way traffic in between (see map at left).

Those general-purpose lanes would run along the right-side curb, which could help discourage any illegal parking; traffic that today uses Western Avenue as a cut-through between Watertown and Cambridge would be redirected to use more frequent-running buses instead, or, if they must drive, to use the parallel Soldiers Field Road.

In earlier iterations of their plan for Western Avenue, BPDA planners had proposed a more modest scheme that would have set aside just one curbside bus lane on the street in order to maintain space for two general-purpose motor vehicle lanes.

But neighborhood stakeholders pushed back and asked the city to be more aggressive in their plans to improve transit service for their growing neighborhood.

“The plan has evolved quite a bit because of the community's response and expectations. And that is pretty well reflected in what we are seeing in the transit corridor proposal: when they first came to us last summer, their plan was very lackluster, and we made sure they got that feedback loud and clear," said Anna Leslie, Director of the Allston Brighton Health Collaborative (ABHC).

“We’ve heard from the community that there’s a desire for better transit. We think this has a lot of merit and fits with city goals," said Boston Transportation Department transit planner Matt Moran in a January presentation about the transitway concept. "Working within the existing streets, it utilizes existing infrastructure much more efficiently, it will reduce transit delay and increase reliability, and it will increase person throughput on city streets."

BPDA officials say that the transitway is a longer-term concept that will require additional space for the public right-of-way, but because much of Western Avenue today is lined with parking lots and aging commercial buildings, and because of its current rezoning effort, the agency expects new development to happen relatively quickly.

Four projects fronting Western Avenue that propose to build over half a million square feet of lab and office space plus 973 apartments are already in the BPDA's approval pipeline.

In the shorter term, BPDA is recommending a street redesign that would work within the existing street's right-of-way by replacing on-street parking with protected bike lanes.

One BPDA-approved development, the three-building "NEXUS" lab complex at 250, 280, and 305 Western Avenue, has already agreed to provide those necessary setbacks that would be necessary for the future transitway when it goes under construction. The project will also build wider sidewalks and raised, physically-protected bike lanes along its two-block frontage of Western Avenue (see rendering below).

Crucially, the new transitway could support significantly increased bus service along the street to a degree that would be necessary to serve the anticipated new development and transform the district from a relatively car-oriented one to a more walkable, transit-oriented neighborhood.

The current schedules for the 70 and 86 vary considerably depending on the time of day: they run up to every 8 minutes during peak hours, but 30 to 40 minutes can pass between buses at other times of the day.

Western Avenue has been identified in preliminary maps of the T's bus network redesign as a "high-frequency" bus corridor where buses would run every 15 minutes or more between Watertown to the west and Harvard and Central Squares to the east.

Traditionally, traffic modeling for new development would assume that those new offices and homes would generate some fixed number of new car trips per home or office cubicle. But with its Western Avenue planning, the BPDA is taking a new approach – one that assumes that Boston will actually improve transit and meet its climate goals.

"The key assumption of this strategy is that members of the public will use better bike or transit connections and change their mode of travel when these options are available to them," wrote Jeff Thomas, a BPDA comminications specialist, in an email to StreetsblogMASS. "This has been seen in recent local examples - including a 20 percent decrease in traffic at intersections near Boston Landing Station after that station opened, despite strong population/job growth in Allston/Brighton, and a 13 percent reduction in traffic on Brighton Avenue after the bus lane opened."

Anna Leslie of the Allston Brighton Health Collaborative notes that strict limits on off-street parking construction will also be critical to meeting those mode shift goals. While the BPDA recently set maximum parking ratios for large new developments, those ratios are still relatively high for the Western Avenue corridor.

The three-building NEXUS project, which the BPDA approved before establishing the new parking rules, is unlikely to be set a strong example for the neighborhood's transit-oriented future, either. As proposed, it will come with a huge 668-space parking garage – considerably more parking than the BPDA would allow if it were seeking its approvals today.

Learn more:

Watch the January 27, 2022 BPDA presentation on the Western Avenue Corridor Study recommendations, or download the slide deck.