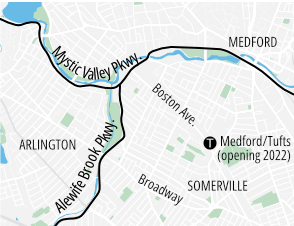

Advocates gathered at Alewife Brook Parkway on Tuesday evening to prepare for what they expect will be a years-long effort to slow down traffic and improve safety along the four-lane roadway that divides Somerville and Arlington. But the event unexpectedly yielded some tangible immediate improvements for pedestrians, thanks to the teamwork of an area high school student and a high-ranking transportation engineer from the Department of Conservation and Recreation.

Alewife Brook Parkway and the Mystic Valley Parkway, also known as Route 16, are identified as a "high-crash corridor" in Somerville's Vision Zero action plan, and the state's crash database records over 140 crashes along the roadway between Massachusetts Avenue and the Mystic River since the beginning of 2019.

Along the roadway's western edge lie the park facilities of the Alewife Brook Reservation, with its sports fields, playgrounds, and a public pool; on the east side of the parkway lie densely-populated residential neighborhoods, including several public housing complexes and a Stop & Shop supermarket.

Like many of the region's more dangerous multi-lane roadways, Route 16 is under the jurisdiction of the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), which means that Somerville's local officials don't have much leverage to implement safety improvements.

So, copying a strategy the group employed last year in securing safety improvements for the "corridor of death" along I-93, activists from the Somerville Alliance for Safe Streets (SASS) are enlisting state and local elected officials to wrangle the state's highway bureaucracies into prioritizing safety improvements.

The "walk and talk" event on Wednesday evening brought out dozens of neighborhood advocates, including Somerville city councilors, local transportation engineers from the public and private sectors, state Rep. Christine Barber, and state Sen. Patricia Jehlen.

"This is not fast stuff. This is probably going to take at least two years of planning, and then we need money for implementation," warned Sen. Jehlen at a brief rally before Tuesday evening's walk. "(But it also) takes your persistence and staying involved and not getting discouraged."

A handful of significant safety improvements are already in the works. As part of a redevelopment of the Clarendon Hill public housing neighborhood, the intersection of Alewife Brook Parkway and Powder House Boulevard, which is currently configured as a large, misshapen traffic circle, will be converted to a smaller "T" intersection, and the Parkway's four-lane cross-section will be reduced to three lanes (with one turning lane, plus through lane for each direction) at a new traffic signal.

Plans also call for a short segment of physically-protected bike lanes on Powder House Boulevard leading from North Street to the Alewife Brook bike path on the west side of the Parkway. Work on this project is expected to begin later this year.

Senator Jehlen and Rep. Barber also told participants that they secured $100,000 in the 2023 state budget to fund a study for the adjacent intersection of Broadway and Alewife Brook Parkway, next to the Stop & Shop, where advocates hope they can implement a similar road diet.

Broadway is about 900 feet away from Powder House Boulevard along the Parkway, and advocates reason that if both intersections are reduced in size to allow only one through-lane for motor vehicles, than adjacent sections of the Parkway between intersections could be transformed into an ordinary 2-lane street in order to shorten crosswalks and recover more space for parkland.

"Our city has been working tirelessly with our state agency partners, who are also change agents. They're here, and they care," said Brad Rawson, Somerville Director Transportation & Infrastructure, at the pre-walk rally. "If there's one takeaway I'd like all of you to have from this evening, it's that government can do things."

Later that evening, after the rally's participants split into groups to walk along the parkways, a DCR official would prove Rawson right.

While evaluating the area's intersections, multiple participants in the walk took note of how little time the parkways' traffic signals offered for pedestrians to cross safely. Here's one group using the crosswalk at Boston Avenue early Tuesday evening – note the Somerville police officer on the right, who steps off the curb to cross just as the flashing red hand turns on, and is only halfway across when the walk signal switches off and the light turns green:

In another group, Petru Sofio, an Arlington High School student and transportation safety advocate, noticed a similar problem at Broadway: the walk signal wasn't long enough for an able-bodied adult to make it all the way across the street.

"At Broadway, it's a 44-foot-wide road to cross. You divide that by the 3.5 feet-per-second rule for walking speed from the MUTCD, and you get a time of 12.57 seconds that you need the flashing red hand to cross," Sofio explained to StreetsblogMASS by phone on the morning after the walk.

Sofio happened to be walking with Jeff Parenti, the DCR's Deputy Chief Engineer, and he showed Parenti his math.

Parenti agreed that the traffic signal wasn't timed correctly – and then, he fixed it.

"He went right to the (traffic signal) cabinet, opened it with his key, and changed it right there," said Sofio, who also captured the moment with the photo at the top of this article.

Sofio and Parenti later walked with the rest of their group to Boston Avenue and made a similar adjustment there, increasing the flashing red walking time from 7 seconds to 12 seconds.