Like many parking lots, the one on Foster Street in the North End is easy to overlook. It's the kind of place that few people care about: a dead-end alleyway with trash collecting in its corners and about 18 cars parked haphazardly among its potholes.

But unlike most parking lots, this small plot of pavement is technically a public park.

According to the 2020 Boston Parks and Recreation Department's directory, the 0.11 acre parcel at 15 Foster Street is officially known as "Foster Street Playground," originally acquired as parkland in 1930.

In a March 2020 op-ed for NorthEndWaterfront.com, Peter Petrigno, an abutting property owner, recalled how car owners took advantage of the city's neglect to take over the property:

"I played there everyday as a child. It was my backyard. As the demographics of the area changed and fewer children were playing there, the city completely abandoned the property. Cars eventually started parking there. When the city didn’t take notice, more cars parked there. After a number of years, someone apparently with connections to City Hall, had neighborhood parking signs posted. I say ‘apparently’ because the Public Works Department does not have jurisdiction of the property, and therefore would not post signs as a matter of their standard practice."

A Boston Parks and Recreation Department official confirmed some of those details on Thursday.

"At some point in the late 80s, the community and local elected officials opted to convert the tot lot into parking. It is North End resident parking only," wrote a spokesperson in an email message.

Now, after decades of neglect, the city is finally taking some responsibility for the property. But instead of planting trees and gardens or installing playground equipment, the city plans to surrender the property to private car storage by spending over $50,000 to pave the "park" under a fresh layer of asphalt.

At an online North End/Waterfront Neighborhood Council meeting earlier this week, Councilor Lydia Edwards, who represents the North End, told participants that "the RFP (request for bids) for Foster Street Park has gone out – that's the park that's paved over where people are parking on it. It's cracked and it's a mess, so we got that in the budget to make sure that that was going to be repaved properly, and it will continue to be a parking space."

The news didn't elicit any reaction from the neighborhood council – perhaps because many North End residents are unaware that the parking lot is actually their public parkland.

Adam Balsam, a neighbor who has lived in the North End for "about 20 years," says that he's "never heard (the park) discussed formally, never been aware of any hearing. I wouldn’t even be aware that it was a park except I stumbled across an old city map.”

Balsam started tweeting about Foster Street Playground after the neighborhood meeting, and is hoping to influence the city to re-claim the property as public parkland. He'd like to see the park restored as green space to support "active recreation of some kind, instead of passive storage for private property.”

According to Census survey data, roughly 60 percent of households in the surrounding North End neighborhoods do not own any motor vehicles. Among the roughly 1,000 households that do own cars, the 18 spaces at Foster Street Playground benefit fewer than one percent of those households.

And while rent at other North End parking lots and garages ranges from $350 to over $500 a month, the lucky few who store their cars in Foster Street Playground pay the city nothing for their use of the public property.

Petrigno, the owner of an adjacent apartment who wrote about the park for NorthEndWaterfront.com, says that he'd also like to see a restored park on the site someday, but he's also grateful that the city is making plans to finally fix the property's broken pavement.

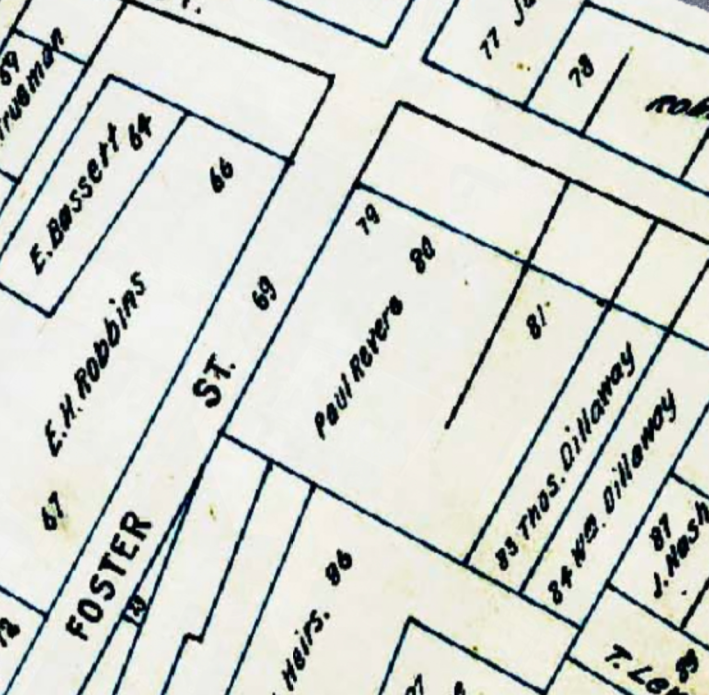

Petrigno notes that the parkland occupies part of the site of Paul Revere's first iron and brass foundry, which was built on the corner of Foster and Lynn (now Commercial) in 1797:

Reached by phone on Wednesday, Petrigno said that he and his family have “been trying to get the city to take care of this park for 40 years.”

“Ideally I would like it restored as a park, but realistically... after battling City Hall for 40 years, I’m going to take what I can get," said Petrigno. "Councilor Edwards is the first city official to actually address the park’s neglect. So I’m grateful that I’m not going to get the run-around forever. I was ecstatic when I heard the news that they would resurface it and keep it clean.”