In the past week, regional planning organizations have released two studies that take stock of the Boston region's growing bike infrastructure – and how that infrastructure is increasingly expanding into lower-income neighborhoods and neighborhoods of color.

The first analysis, A Decade of Bluebikes in the Boston Region by Betsy Harvey and Ariel Patterson of the Boston Regional Metropolitan Planning Organization, looked at access to Bluebikes stations since the regional bikesharing system launched in 2010.

When the system then known as "Hubway" started, it only had 60 stations in the city of Boston, and only served a handful of the core neighborhoods near downtown (it also shut down completely for several months each winter).

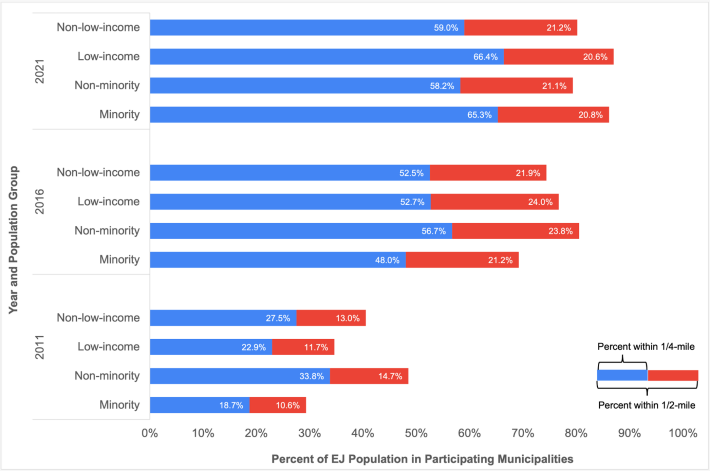

According to Harvey and Patterson, only 19 percent of Boston's non-white population lived within a quarter-mile walking distance of a bikesharing dock in 2011, but 34 percent of Boston's white residents did. Similarly, higher-income residents were more likely to live in Hubway-served neighborhoods in 2011 than lower-income residents.

By 2016, though, Hubway had expanded to include four cities and towns: Boston, Brookline, Cambridge, and Somerville. It had also expanded into more diverse neighborhoods within the City of Boston, including Roxbury, Dorchester, and East Boston.

Additional expansions into even more communities since then have apparently eliminated the system's racial disparities: in fact, in 2021, non-white residents living in Bluebikes host communities are actually slightly more likely to live near a bikesharing station than white residents, according to Harvey and Patterson's analysis:

Two caveats about this analysis: the authors used decade-old demographic data from the 2010 Census to perform their analyses. Some neighborhoods in the Bluebikes region have changed significantly since then, but neighborhood-level race and income data from the 2020 Census isn't yet available.

The authors also admit that they use a very basic definition of "access" by relying on geographic proximity alone. "Other analyses could incorporate a broader definition of 'access' to account for the presence of safe bicycle infrastructure nearby, equity of costs to users, and the ability of bikeshare to provide access to various destinations such as jobs and essential services," they suggest.

Luckily, their colleagues at another regional planning agency, the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) are working on that.

MAPC recently published their first "Metro Boston Municipal Trails, Bikeways & Greenways Inventory," which is intended to become an annually-updated report on the region's progress in implementing a connected network of off-street trails and on-street protected bike lanes.

“We wanted to look at how complete or robust is the network we have, and be able to rank progress across communities," the report's lead author, David Loutzenheiser, told StreetsblogMASS last week. "It shows how communities compare – what’s typical, and what’s not. Frankly there are a lot of communities that have a lot of work to do.”

The analysis used year-end 2020 trail and bikeway data from the MAPC Trailmap, an inventory of regional bike and pedestrian infrastructure, and compared municipalities' access to safe walking and biking infrastructure by measuring the number of bike lanes per mile of roadway, and comparing trail mileage to each city's or town's total square mileage.

By those measures, the City of Cambridge is a clear regional leader: Cambridge has 2.8 miles of shared-use pathway per square mile, and about 15 percent of its busy arterial and collector streets have some form of a protected bike lane (that figure has increased since the report's data was collected, with several new protected bike lanes debuting in recent months).

For on-street protected bike lanes, the City of Somerville is close behind: a little over 10 percent of its busiest streets had some form or protected bike lane at the end of 2020.

The City of Boston has the most protected bike lanes by mileage (over 18 miles), but those facilities only cover about 5 percent of the city's arterial streets, and they're a long way from being connected in a cohesive network.

The analysis also analyzed access to the regional trail network from non-white and lower-income neighborhoods. "Urban core communities with environmental justice populations are generally well-connected via a shared-use path network," write the Inventory's authors, thanks to facilities like the East Boston Greenway, the Neponset River Greenway in Mattapan and Dorchester, and the Southwest Corridor through Roxbury.

The Inventory also names five proposed greenway links that should be prioritized to "significantly improve access to (environmental justice) populations." Those projects include the Swampscott Rail Trail (connecting the Northern Strand in Lynn to Salem), the Mass Central Rail Trail in Waltham and Belmont, trail gaps in Peabody and Salem, and the final segment of the Bruce Freeman Rail Trail through Framingham.