Editor's note: this piece originally appeared in Greater Greater Washington and is being reprinted here with permission.

Washington, D.C.'s Metro announced in mid-June that it would bring some 7000-series trains back online over the coming weeks, bringing relief to riders from months of painfully irregular service. After nine months of investigation, operator training, and changes to management and protocols, the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) will still need to get approval from the Washington Metrorail Safety Commission (WMSC) over later phases of the return-to-service plan in order to ensure that safety standards are met.

But traffic violence causes many more deaths and injuries than public transit: one in a hundred of us will die from it in our lifetimes. Why do authorities treat traffic safety as though it’s less important than transit safety?

Anatomy of a safety-first shutdown

The impacts of half of Metro’s trains being offline for most of a year, just when more people were returning to Metro, are hard to quantify beyond “probably quite significant.” Anecdata abound of would-be riders giving up in frustration as they waited 15, 20, 25 minutes for a train, with no break on peak fare charging. The alternatives for many riders are driving, not traveling to work or services, being late, or taking less-efficient modes. That’s bad news for individuals, safety, other drivers, the economy, or simply a functional region with a mobile population.

WMATA had pulled the trains out of service following a derailment in October 2021, under the directive of the WMSC, which cited concerns that wheel alignment issues might cause future derailments. (The scope of WMSC’s authority to direct WMATA to pull services is detailed here).

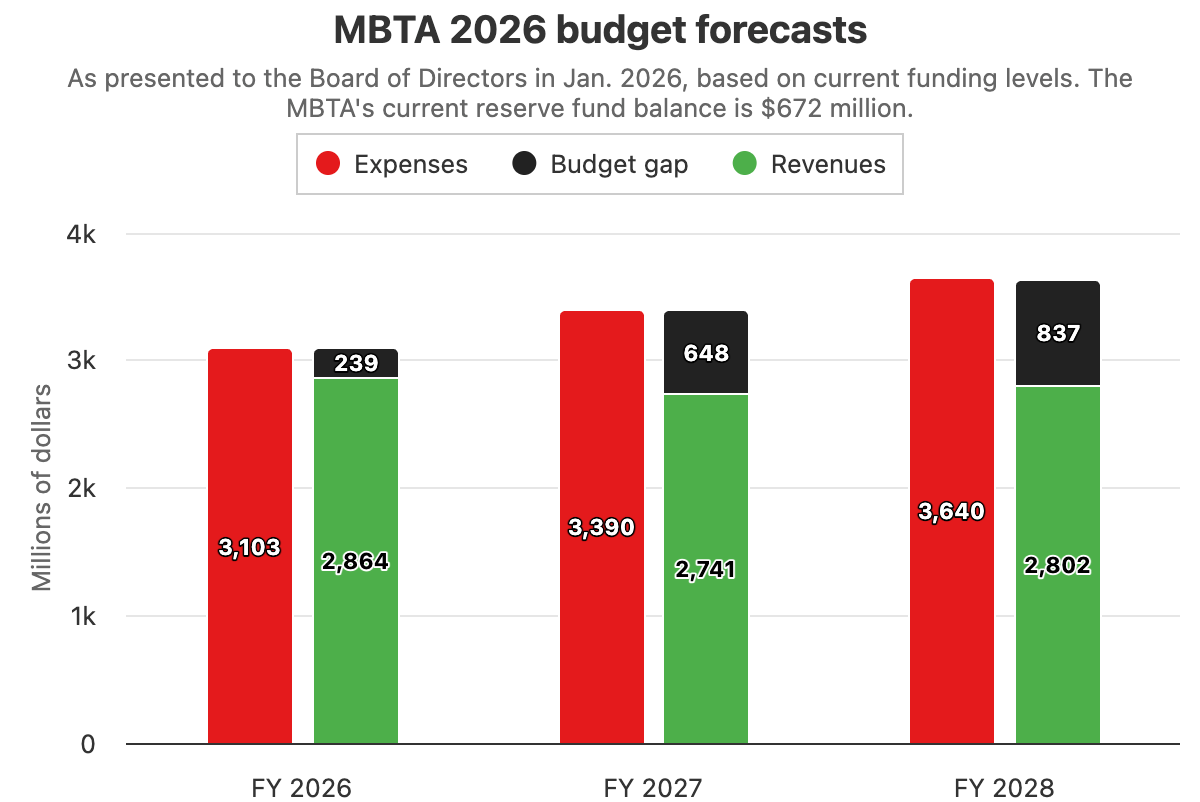

It’s not just our own region grappling with these issues. The Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority is also cutting back on service over the results of a safety review. It’s clear that the official expectation is virtually 100 percent safety on transit. If that standard is not met by the officials responsible for that system, regulators have the authority to shut it down regardless of financial and societal costs until it passes muster. Would-be riders end up in cars, or stuck.

But many, many more people die and are hurt every year by personal vehicles than they are by transit or airplanes. DC alone has experienced 17 deaths (two of which occurred last weekend) and more than a hundred major injuries, including four children and my elderly neighbor, in the last six months, but not a single death or major injury due to transit during that time.

Who’s responsible for unsafe systems?

For some types of transportation, an incident causing injury or death will trigger an immediate regulatory response, which targets the setting where the incident occurred and other factors. Airplanes and mass transit fall in this camp. The authorities’ job is to ensure the agency in question only offers services if it reaches specific standards of safety.

When the WMSC judges that a set of trains or a rail line is unsafe (such as they did last October, after WMATA initially pulled them), they have the authority to keep that mode from operating until they deem it safe. The inconvenience to riders, consequences of missed opportunities such as medical appointments, or effects on the wider economy carry limited weight. This approach echoes that of the Federal Aviation Administration: if a series of planes or an airport doesn’t meet its rigorous safety standards, they can be grounded or closed until those requirements are met.

Reactive measures usually include some combination of grounding or pulling the mode of transportation out of service, plus a full-fledged investigation into how the system failed to avoid a casualty or near-casualty event, such as the 7000-series derailment in October.

Apply that same logic to incidents caused by personal vehicles, and you quickly spot the difference. Traffic violence is one of the highest non-disease causes of death in the US; as noted above, the odds of dying in a car crash throughout your lifetime is around one in a hundred. The same analysis from the National Safety Council puts your chances of dying in a plane crash or transit in the same risk zone as being killed by lightning: literally too small to calculate.

But our legal system and the media both apply a much lower standard of safety when it comes to vehicular violence. (Our legal system goes even further, to grossly subsidize driving.) Transportation departments don’t routinely shut down the site of a car crash until we fix a design issue that led to it, even when it happens more than once. Delayed road safety projects produce deadly and tragic results. Authorities don’t often recall all the cars fitting a make or model when it’s involved in repeated crashes (it does happen sometimes if there’s a demonstrable flaw – but what if the issue is not a bug but a feature?). Our own U.S. Department of Transportation promotes the vehicles most likely to kill people if they do crash!

For cars, to the limited extent that traffic authorities do perceive responsibility, it mainly seems to apply to the individual operator. And that leaves out a huge part of the picture – the systems that will keep reproducing the risk, which becomes integral when regulators take action on transit and planes.

Since I haven’t found anyone to tell me definitively why the focus for traffic is on individuals rather than systems that contribute to crashes, here are a few hypotheses. If the operator of the mode in question is an individual, such as the driver of a single-occupancy vehicle, the state assumes responsibility for risk only at its pleasure, and not as a matter of course. Or perhaps what’s at work is a pernicious and baseless idea that transit and aviation systems can be fixed, but vehicle traffic systems–which are also systems whether or not they’re treated that way–center on individuals instead of institutions, and therefore cannot be regulated in the same way a transit system can. Or maybe it’s down to a tendency for large catastrophic events like plane and train crashes to shock us and cause a fear response, while we’ve become desensitized to the regular occurrence of car crashes.

Should any of the above matter if the goal is public safety? Is it worse if a person dies on a train than if they died from the impact of a driver hitting them with their car? When we know so clearly how to prevent traffic violence, there’s no clear reason not to take it as seriously as we do transit safety.

Symptoms of a healthier approach

At the local level, if local authorities held traffic safety to the same standard as transit, it could look like: lowering speeds on arterial and local roads, pedestrianizing streets currently reserved for car traffic, actively disincentivizing driving by pricing or other means, redistributing space for bus, bike and other non-car modes towards the specific goal of reducing car trips, closing down a street or intersection where a fatality has occurred until the design is improved. Above all, it means having the stomach to make trade-offs that prioritize safety even when drivers are inconvenienced, because convenience doesn’t stop us when transit safety is on the line.

At the federal level, it could involve higher taxes or fees for cars we know to be dangerous (which DC is leading on locally), or raising–for the first time in 29 years–rather than temporarily removing the $0.18 cents per gallon federal gas tax. We could also use clearer leadership from the agencies that set the standards for how we design and regulate our traffic systems (Federal Highway Administration) and how safe vehicles have to be to be street legal (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration).

Some of these things are happening, but sporadically. The fundamental, emergency nature of a safety-first traffic system, where any loss of life is treated like it is on transit, is still a dream in America.

The safest train…is a train, not a car

“The safest train is the one that doesn’t run at all” sums up a lot of transit observers’ frustration when services are pulled for safety protocols, highlighting that no human activity is truly risk-free. Somewhere, decisions have to be made about the balance to strike between the core purpose of any mobility system and safety. However, even this bleak assessment leaves out the fact that putting riders off of transit puts a lot of them in personal vehicles, directly raising the risks of traffic injuries and fatalities.

Other observers have noted that, in WMATA’s case, removal of the 7000-series trains makes transit less accessible to persons with hearing, cognitive, or sensory disabilities.

What’s missing from this puzzle is leaders’ and regulators’ willingness to think about safety and risk holistically. It makes no difference to our moral responsibility to fix the problem whether a person is hurt or killed by drivers or by transit. Ideally neither would happen, and right now, as for decades, driving is held to a much lower standard than transit.

It wasn’t always so: in the early 20th century, traffic fatalities were treated as systematic urban emergencies, a policy approach that car manufacturers and other interests gradually turned on its head through marketing and lobbying efforts. In reading the linked essay, I was reminded of an episode in “The Wind in the Willows,” published in 1908, in which Toad’s mania for driving ruins his life: the connection was unrecognizable to a child raised 80 years later in southern California.

Transit should be both safe and functional in order to serve riders’ needs, and not present unnecessary danger to the public.

But who wins under a system that boots people off of transit into a more dangerous mode of transportation? Until we hold traffic safety to the same standard as transit safety, it’s out of the frying pan, into the fire.

Caitlin Rogger is deputy executive director at Greater Greater Washington.