The Commonwealth's decision to outsource a key component of its climate policy to private car dealerships is going about as well as you might expect.

Roads and highways are the Commonwealth’s biggest source of air pollution, and the state’s strategy to survive the climate emergency leans heavily on getting Massachusetts drivers to buy 200,000 electric vehicles (EVs) by 2025.

But as of January 1, there were only 66,025 true "zero-emission" passenger cars registered in Massachusetts, according to state vehicle registration data.

Adding plug-in hybrid vehicles to the tally (that is to say, cars that can run on either electricity or gasoline) bumps the number up to 104,457 vehicles, according to state officials.

The state is extremely unlikely to close the gap to meet its 2025 goal over the next few months.

Massachusetts car dealers sell over 300,000 new passenger cars a year, but according to the Alliance for Automotive Innovation, EVs made up only 12.6 percent of new car registrations in Massachusetts in the fourth quarter of 2023.

The MOR-EV program, which doles out taxpayer-funded subsidies to drivers who buy new electric cars, issued only 4,246 rebates for new EVs between January and the end of April.

'We don't seem to feel the urgency'

The tailpipes on cars, trucks, and other vehicles generate 37 percent of the state's greenhouse gas emissions, in addition to toxic pollution from exhaust fumes, tire dust, and other automotive secretions.

But in defiance of state laws that require steady reductions in climate-heating emissions, highway pollution in Massachusetts has actually increased for three consecutive years since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic.

"Our climate situation is an emergency, and the state needs to treat it like an emergency," Becca Glenn, the interim Massachusetts state manager for Mothers Out Front, told StreetsblogMASS on Monday. "We’re now at a point where we need to be really aggressive, and we don’t seem to feel the urgency."

Highway agencies face no mandate to cut pollution

The state's EV target comes from the state’s Clean Energy and Climate Plan, the current version of which was published under Republican Governor Charlie Baker's administration in June 2022.

The 2021 "climate roadmap" law requires the Commonwealth to set a statewide emissions limit and sector-specific sublimits every 5 years, along with "a comprehensive, clear and specific roadmap plan to realize said limit."

Other states with leading climate policies have also adopted aggressive EV targets, but, unlike Massachusetts, they are also holding their highway agencies accountable for cutting pollution on their soot-caked highways and investing in transformative improvements to public transport.

For instance, California is aiming for a 15 percent reduction in total light-duty motor vehicle miles traveled (VMT) by 2050 by taxing fossil fuels to invest in new transit projects and building more housing in walkable neighborhoods.

Washington's state climate plan calls on its Department of Transportation to “make VMT reduction, efficiency, and equity explicit priorities for transportation funding.”

The Massachusetts climate plan acknowledges that EVs alone won't be sufficient: the state will also need to "achieve a modest reduction in total vehicle miles traveled compared to baseline projections, in spite of continued projected population and economic growth, by providing more Massachusetts residents with more alternatives to personal vehicles."

But to date, state government has yet to impose any specific mandates for its highway agencies to reduce pollution or improve transit access.

Glenn, of Mothers Out Front, observes that an exclusive focus on electric vehicles is also unfair to poorer, transit-dependent communities.

"In our environmental justice communities, where there are higher rates of asthma from the particulate matter coming from highways – those are not the people who are going to go out and buy a new $40,000 electric car," says Glenn. "Let’s promote EVs, but we can’t balance the entire plan on that – we need reliable transit, we need to look at more efficient buildings and those other sectors."

Climate roadmap needs a detour – but MassDOT doesn't want to change course

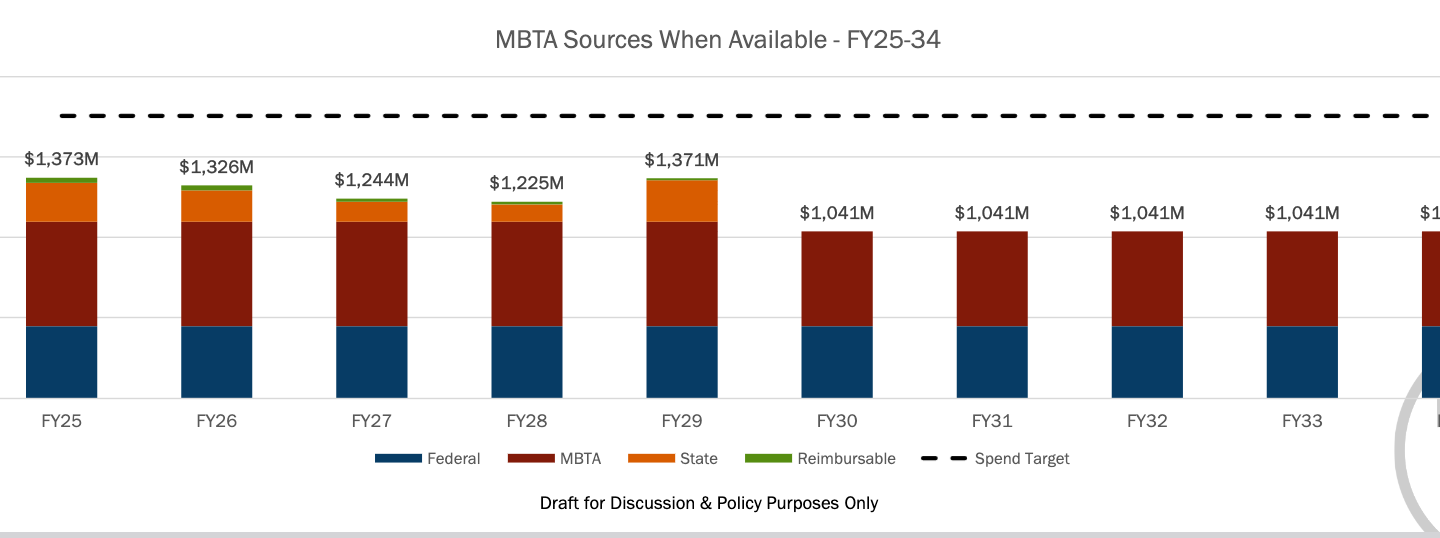

Even as MassDOT advances multiple highway projects that will cost taxpayers several billion dollars, the state government's support for MBTA projects – money the agency needs to achieve a state of good repair – is on track to decline considerably over the next decade.

Major transit improvement initiatives that have the strongest potential to reduce traffic and emissions, like the construction of new garages for an expanded, electrified bus fleet, and the implementation of an electric regional rail system, remain mostly unfunded and in limbo under the current administration.

StreetsblogMASS asked MassDOT officials whether, given the weak impact of EV deployment to date, the agency would pivot to start focusing more on reducing traffic with investments in transit and other cleaner alternatives.

Their answer, in short, was "no."

"First, federal and state statutes and regulations put constraints on how much funding could be shifted from highways to transit," wrote MassDOT spokesperson Amelia Aubourg in an email to StreetsblogMASS. "Second, given the nearly 56 billion vehicle miles traveled in the Commonwealth annually, there are limits to how impactful such a shift would be."

MassDOT’s Highway Division plans to spend $11.2 billion for highway projects over the next 5 years.