Editor’s note: In celebration of the Juneteenth holiday and amid recent conversations about the freedom of movement, we’re proud to offer a three-part series from reporter Meghan Volcy on the intersection of Black history and the pursuit of equity and justice in transportation throughout the United States’ history.

Transportation was and continues to be a space for resistance to white supremacy. There are stories to be told and lessons to be learned from what we’re taught in school, from Homer Plessy’s 1892 arrest on a Louisiana railroad, which sparked the disgraced Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court ruling that established “separate but equal” racial segregation laws, to Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955., which ultimately resulted in new court rulings (Browder v. Gayle) that struck down segregated buses.

But the connection between transportation and Black civil rights goes back to the very first Black Americans, who were kidnapped from Africa and sold as slaves in the colonies that would eventually become the United States.

In Massachusetts, the first ship carrying enslaved Africans touched down in Boston in 1638, marking the beginning of legal slavery in the state. This practice continued on for a century, until slavery was abolished in Massachusetts in the late 1700s.

Later, once the North became a refuge from slavery, transportation across state lines became a means for families to escape slavery. The Underground Railroad, while not a technical railroad, was a series of routes with various conductors – most notably, Harriet Tubman – that helped Black Americans escape the South to “freedom” in the North. Massachusetts had several stops along the Underground Railroad, from the Hayden House in downtown Boston to Ross Farm in Northampton.

While the history of Black Americans and transportation justice began with forced movement in slavery and attempts at escaping, the resistance to transit injustice evolved alongside the fight to exist and move freely in public spaces and American society.

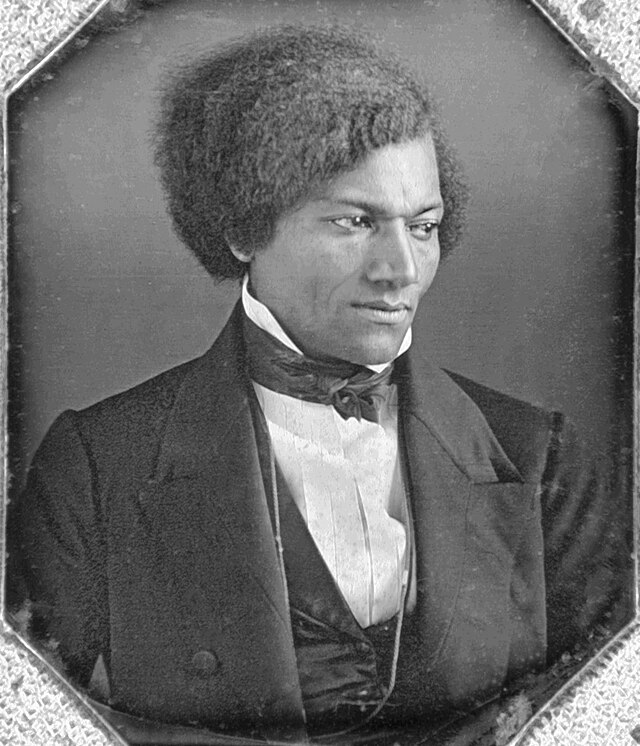

Did you know? The first recorded resistance to segregated transit was in 1841 when Frederick Douglass (pictured) and James N. Buffman refused to leave a train car for white passengers.

Civil War Era

While tensions nationwide were moving towards civil war, in Massachusetts, state laws pushing for integration began taking shape, with integration on mass transportation in 1842 and in public education in 1855.

In the mid 1800s, advocates worked tirelessly to desegregate the school systems of Salem, Worcester, Nantucket, and Boston, which had established separate schools for Black students.

In the early 1850s, Anthony Burns escaped to Boston for a few short, free months, but “under the pretext of being charged for robbery,” he was recaptured and sent back into slavery. However, less than a year later, Burns was able to return due to a Black church raising money to buy his freedom.

From coast to coast, Black Americans were risking their lives in pursuit of justice. In New York, Elizabeth Jennings Graham refused to leave a “Whites Only” streetcar, and in San Francisco, Charlotte Brown sued the city’s streetcar company only serving white people every time she was penalized for not leaving.

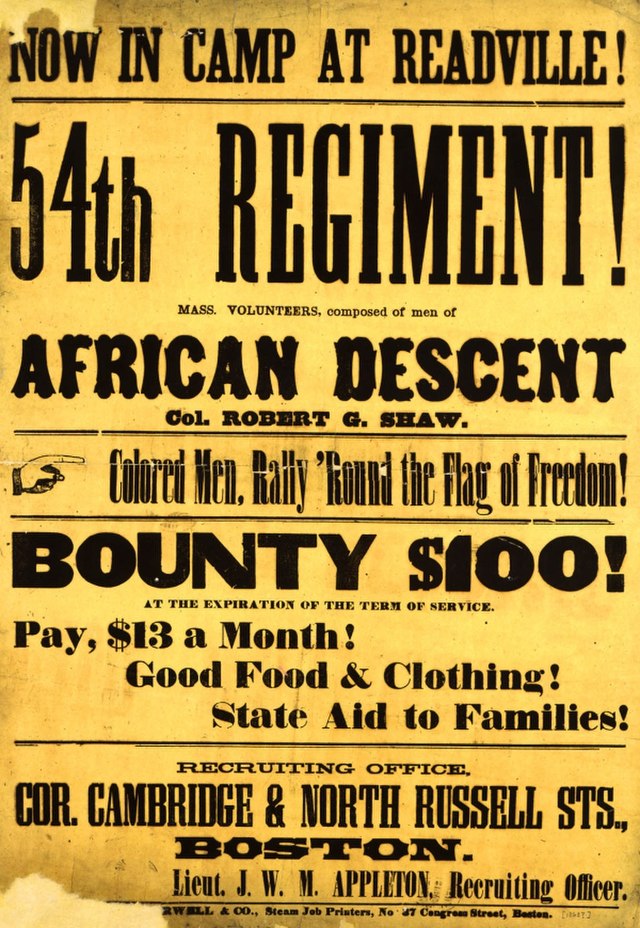

On the edge of Boston Common on Beacon street, there is a statue of soldiers that I (and likely you) have always walked by. This monument is dedicated to the 54th Black Regiment. During the Civil War, Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew with the help of local Black leaders like Lewis Hayden recruited Black soldiers to fight in the Civil War. Over 180,000 Black men joined this regiment and the sheer number also allowed for the formation of the 55th Regiment.

Robert Gould Shaw led the 54th, and in this time, they saved soldiers from the Tenth Connecticut from Confederate troops on James Island and most notably, led an assault on Battery Wagner, in Charleston, South Carolina – which Harriet Tubman witnessed from a distance.

This was a physical defeat in that the 54th Regiment lost nearly half of their men, but a symbolic victory as it convinced the general public that Black men were essential to the Union’s efforts. This gave way for Black men to serve in the Union Army, which helped the Union’s victory in 1865, one of the pivotal moments that abolished legal slavery from the United States.

Reconstruction to Present Day

Following the Civil War and the abolishment of slavery, Reconstruction was a time where the U.S. government attempted to reintegrate the Confederate states and redesign an American society without slavery. This included the introduction of public education and government-provided social services, and passing of the 13th through 15th amendments.

The Reconstruction Amendments and Their Failed Promises

The 13th Amendment, passed in 1865, abolished slavery, except as punishment for a crime. In the present day, this exception has resulted in mass incarceration disproportionately targeting Black Americans.

The 14th Amendment, passed in 1868, granted citizenship and equal protection to all people born or naturalized in the United States. In the present day, this amendment is currently under siege by the new administration trying to end birthright citizenship.

The 15th Amendment, passed in 1870, allowed Black men the right to vote. Jim Crow laws and voter suppression tactics like literacy tests often kept this right from being actualized. In the present day, voter suppression tactics like threatening polling locations, gerrymandering districts, and setting fire to ballot drop off boxes disproportionately threaten Black people’s right to vote.

However, the 12 years of Reconstruction-era governing faced violent opposition from white supremacists, giving way to nearly a century of regression in the Jim Crow era, weaponizing policy to segregate, discriminate against, and disenfranchise Black people.

The low bar set in the Jim Crow era allowed for the treatment of Black Americans as second-class citizens and the relegation of Black Americans to the fringes of society.

Through racist laws and their lawmakers and enforcers, Black Americans were segregated, ostracized, and underserved by their governments. In a shameless display of double standards, white people were rarely held accountable by the same law enforcers when continuing to violently dehumanize Black people in public lynchings, beatings, hosing, and worse.

Black Americans fled to the North to escape the South’s severe discriminatory practices and policies, but the North was not the safe haven general history teachings have made it out to be.

For example, in Massachusetts, there was an unofficial color line that prevented African-Americans from easily obtaining housing outside of certain areas (like Wards 1 and 2 in Holyoke and the Willow and Cross streets area of Springfield).

The late 1960s marked the end of Jim Crow, through major policy shifts in the passage of the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act.

However, this time period also saw violent acts of white supremacy in the assassinations of Civil Rights leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X, both of whom spent formative years in Boston.

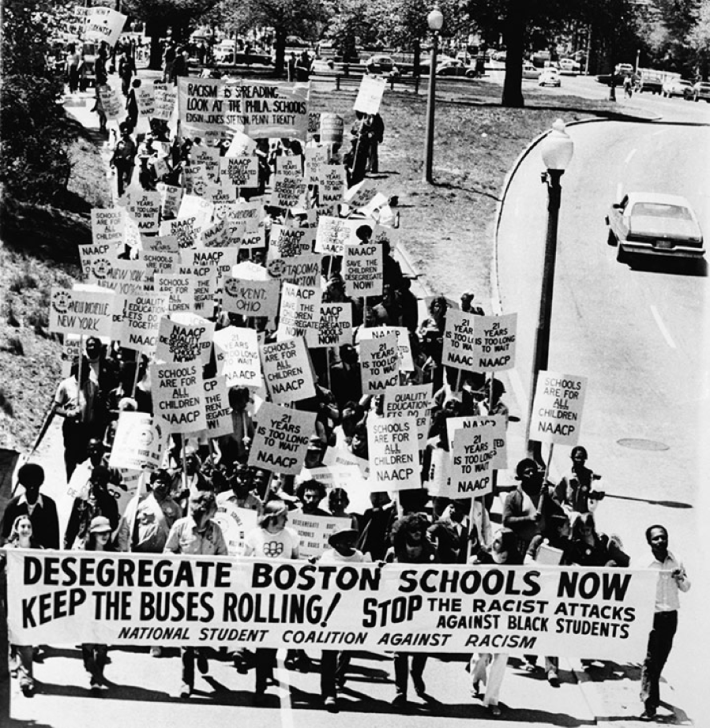

The white supremacist resistance to the turning tides of legalized racism was particularly felt in Boston, as court-ordered attempts to desegregate the Boston Public Schools were met with physical, emotional, and legal aggression in the 1970s and 1980s.

Once again, transportation played a key role: courts mandated that Boston schools would be integrated by busing students out of segregated neighborhoods. Busing lasted from 1974 up until 1988, when full control of the desegregation plan was shifted to the Boston School Committee.

Over the course of those 14 years, the school district shrank from 100,000 students to 57,000, as white families fled for private schools and suburban districts. The effects of that “white flight” linger to this day: in 2014, half the population of Boston identified as white, but only 14 percent of students in the Boston Public Schools identified as white.

Looking Ahead

In trains, streetcars, and buses, Black people across the country embodied resistance – they advocated, they organized, they fought back, they took up space, they rested, they demanded access, they made their own way, they challenged the law.

This is just the beginning – the next part of this series will look at Black transportation justice and the intersectional acts of resistance that pushed for transportation justice from union halls and courtrooms to city streets and buses.

Then, in part III, we’ll examine how this legacy lives on today in the push for fare equity, transit worker protections, and housing justice in transit-oriented development.

Stay tuned for part II, coming on Monday.