Today, while segregated transportation is no longer legal, we still see and live in the effects of racial disparities in transportation – highways ripped through Black neighborhoods, transit projects and systems defunded, car dependency increased.

However, we are also moving through a world shaped by the progress and victories of those who came before us. Black people are riding some of the very transit systems they fought to integrate, leading transportation agencies and initiatives that once excluded them, and continuing to push for equitable, sustainable, accessible mobility for all.

Who’s allowed to live near transit?

Redlining in the 1930s labeled inner-city BIPOC and immigrant neighborhoods as “high-risk” for investment, restricting their access to home loans and opportunities to build generational wealth. As a result, these communities began to suffer from underfunded infrastructure and public transit.

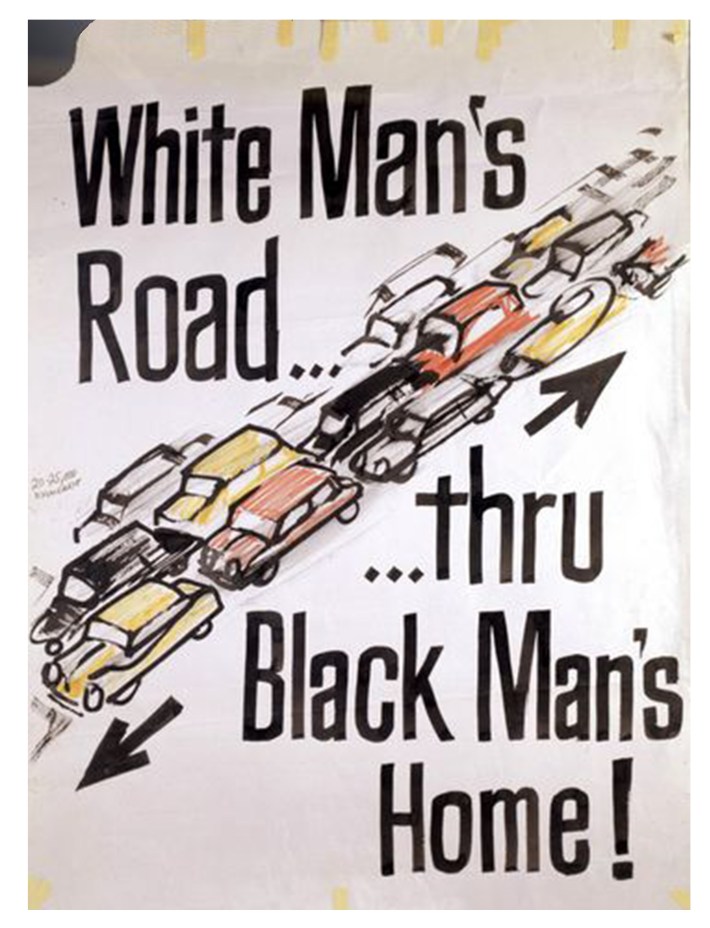

The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 allowed state and local governments to direct highway construction to disproportionately cut through Black communities across the U.S., displacing families and destroying neighborhoods of cultural and economic vibrancy.

The Black and Brown families who weren’t displaced found themselves living in neighborhoods exposed to hazardous air and noise pollution, resulting in a denigrated quality of life and long lasting health effects. To this day, highway pollution is significantly worse in communities of color.

Highways, fears of desegregation, and discriminatory housing policies also resulted in urban sprawl and white flight. As white people left for the suburbs, so did government resources. This disinvestment left urban city centers with reduced public services – including transportation – reduced economic opportunity, and less safety.

Now, as cities have become more attractive again, white and wealthier people have been returning and sparking gentrification. Without corresponding investments in affordable housing, transit improvements marketed as revitalization efforts have contributed to higher rents and higher costs of living, driving people of color and lower-income residents out of transit-accessible neighborhoods or out of the state altogether.

There could be a beautiful new bus stop or commuter rail nearby, but what good is that if the people who’ve lived there their whole lives can’t afford to stay?”

Shavel’le Olivier, Executive Director of the Mattapan Food and Fitness Coalition.

In 2021, Masssachusetts passed the MBTA Communities Act, a state law requiring the 177 cities and towns serviced by the MBTA to zone for multi-family housing near public transit.

The intended impact is to promote housing density and affordability in transit and walking-friendly areas, particularly in communities that have historically resisted such growth.

The law has been a big step in developing transit-oriented housing and addressing multiple intersecting policy and justice issues, yet there are many misconceptions about the law, and defenders and advocates of this policy still face regular challenges to its implementation and impact, especially in wealthier, majority-white suburbs.

To continue on this path to undoing historical harm and cultivating future justice, we must continue to hold equity and accountability at the center of this law’s enforcement.

Public transit and policing

Despite being a public good, public transit has become a space for racialized policing, resulting in further harm to the Black community.

Nationally, Black riders are disproportionately targeted, cited, and arrested for fare evasions, ultimately failing to address systemic transit inequities while reinforcing racial disparities in mobility, economic opportunity, and policing.

In 2018, the Conservation Law Foundation and Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights found that 14 out of the 19 people (74 percent) who were arrested for fare evasion were people of color, even though the majority of the MBTA's riders are white.

"The fines are draconian. If you didn’t pay your $1.70 bus fare, you have to pay $100 for your first infraction," transit advocate Mela Bush-Miles told StreetsblogMASS in 2020. "If you don’t pay for parking in the commuter rail parking lots, the fine is only one dollar (plus the unpaid parking fees). So who makes these rules?"

In 2021, Governor Charlie Baker proposed and ultimately enacted reforms to the state’s laws that considerably reduced fines and prohibited arrests for transit fare evasion.

In 2023, Jordan Neely, a 30-year old Black man experiencing homelessness, was put into a chokehold and killed on an MTA train by a fellow rider, 24-year old Daniel Penny, a white man and Marine veteran. Penny’s manslaughter charge was dismissed, and he was acquitted of negligent homicide last December. His acquittal drew widespread backlash from civil rights activists, while right-wing supporters praised him, to the point of the new Vice President even invited him to the Army-Navy football game as his guest.

Despite these systemic challenges, the fight for transportation justice is ongoing. Advocacy groups push for initiatives like fare-free public transit, protections for transit workers, and government investments in Black and brown communities historically neglected and denigrated by urban planning decisions.

Black communities have never stopped fighting for the freedom to move safely and with dignity. We can continue this movement towards justice, liberation, and equity for all through advocacy, organizing, fighting back, taking up space, resting, demanding access, making our own way, challenging the law – just as those before us did.

Transportation justice is about so much more than getting from point A to point B. From the first refusal to move on a segregated train car to modern-day demands for fare-free transit and housing equity, transportation justice has intersected with climate justice, health justice, racial justice, housing justice, education justice, and economic justice.

The right to move freely, safely, accessibly, and affordably is critical when we talk about liberation. Liberation for Black people also means liberation of all people of color Native and immigrated, LGBTQIA+ people, disabled people, working-class people, young people, old people, women and nonbinary people – anyone who has been shut out or kept from equity and freedom in movement.

When we fight for equity and justice in transportation, we carry the torch on a centuries long fight for a future where we can all thrive without barriers to mobility. We’re not just honoring that legacy, we’re extending it and fulfilling some of our ancestors’ wildest dreams.

Read more from reporter Megan Volcy's special report on Black history and transportation justice: