The MBTA's Route 28 bus ranks as the region's highest-ridership bus route with over 12,000 riders on a typical weekday. When it runs according to schedule, that bus takes about 30 minutes to traverse the 4.1 miles between Mattapan Square and Dudley Square – an average speed of about 8 miles per hour.

The City of Boston is currently gearing up two planning efforts to improve transportation, safety and public spaces on the two major streets where the 28 runs. One planning effort will focus on Blue Hill Avenue between Mattapan Square and Grove Hall in Dorchester, and another will analyze possible time-saving improvements for bus riders on Warren Street, where the 28 joins four other high-ridership routes on their way to Dudley Square Station.

The city reports that, because of traffic congestion, the "average bus rider experiences 20 minutes of longer-than-necessary travel on Warren Street each day." The vast majority of Warren Street's bus riders self-identify as people of color, and the current design of the street, which lacks bus lanes or other bus-prioritization features, forces them to waste tens of thousands of hours stuck in traffic every week.

While the city and neighborhood groups consider ways to improve conditions for bus riders on these streets, one failed concept looms large – the state's 2009 proposal for the "28X," which would have installed a dedicated busway in the median of Blue Hill Avenue and extensive new bus lanes on Warren Street to become the city's first "gold standard" bus rapid transit route.

Jim Aloisi was the Massachusetts Secretary of Transportation under Governor Deval Patrick in 2009, and one of the chief proponents of the 28X idea.

"Congress had just passed the stimulus act... They wanted 'shovel ready' projects. Typically that would mean road projects. But my criteria was, give me some bold ideas for investing in public transit and equity," said Aloisi in a phone interview Thursday.

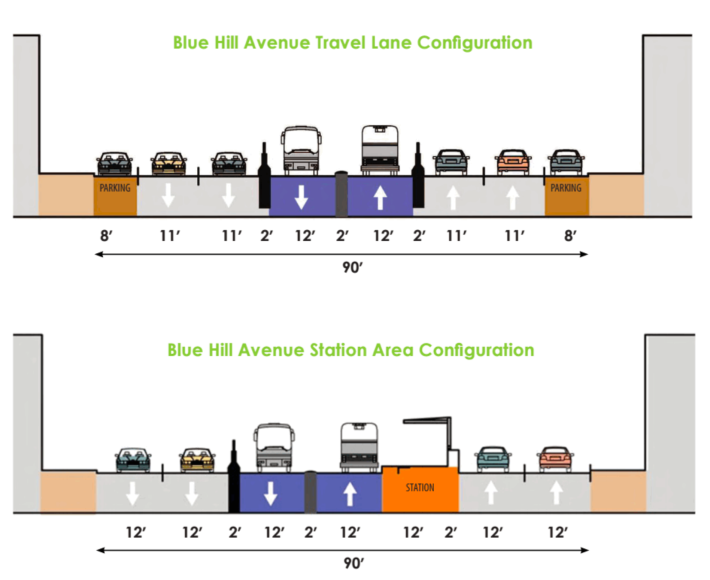

"The planners came back and said we could do BRT (bus rapid transit) on Blue Hill Avenue. For many years people chafed under the idea that Silver Line was characterized as BRT. It’s not true BRT. BRT should have its own dedicated lane, level boarding platforms, traffic signal preemption and all sorts of other things that the Silver Line doesn't have. On Blue Hill Avenue, it's such a generously wide, straight road, we decided we could do bus rapid transit right. You could serve people from Mattapan to Dudley Square."

"The problem we had was, because it was being funded out of the stimulus bill, everything had to move quickly," continued Aloisi. "Where the city is right now doing an appropriately lengthy outreach project, we just couldn’t do it. We had people who wanted light rail instead, and other people were concerned about changes to the neighborhood, like not being able to double-park any more, or losing the street trees. We tried to give people assurances that we would deal with those issues in a responsible way, but we just didn’t have time."

In the face of opposition from local legislators, the state withdrew its application for federal funding for the project in November 2009.

Steve Poftak, the current General Manager of the MBTA, offered his own analysis of the project's failure in a post-mortem he wrote for the Pioneer Institute in 2009, where he was working at the time. He agreed that the project failed because of its ambitious timeframe, which prevented the state from collecting sufficient neighborhood input. "It’s too bad — this would have been a useful project and great proving ground for BRT concepts," wrote Poftak at the time.

Aloisi, now a board member of TransitMatters, still strongly believes that the city and the MBTA have a responsibility to improve bus service on Warren Street and Blue Hill Avenue, and he's hopeful that some of the ideas from the 28X concept might find more traction today.

This time around, he says that the city should take advantage of more public outreach opportunities, focus on bus riders, and work hard to address the neighborhood's concerns over gentrification – one of the more substantive issues that sank the 28X proposal.

"Many people fear that you’ll improve transit and the public realm to the point where you’ll gentrify the neighborhood and push people out... That happened like brushfire in the South End when the old Washington Street elevated came down. So we’ve got to combine improvements to public transit with assurances – whether rent control, or commitments to build new affordable housing – that we’ll act to prevent the kind of displacement that’s happened in other places."

"I still think it’s the right thing to do," says Aloisi. "We’re living in a moment when people are hungry for bus rapid transit. Maybe we were ten years too early. I regret we didn’t do it, but I think we set the stage for some of the conversations that are happening today."

Take the city's survey on mobility along Blue Hill Avenue

Read the state's 2009 federal stimulus grant application for the 28X project