In its new "roadmap" plans for eliminating greenhouse gas pollution, Governor Baker's administration projects that Massachusetts households will not make widespread shifts in their travel habits to embrace transit, walking, or biking in the coming decades, and that the state will spend tens of billions of dollars to subsidize new electric cars.

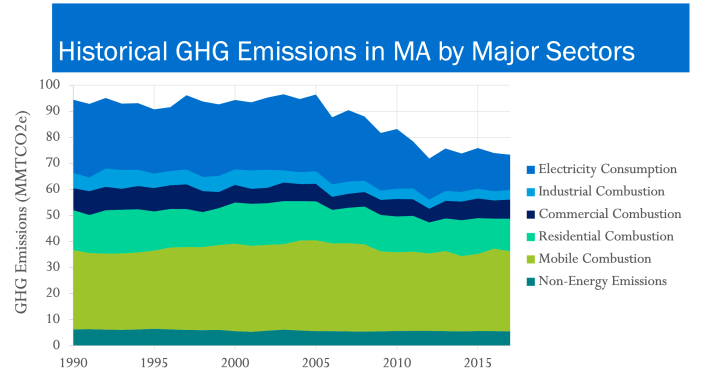

Motor vehicles are by far the Commonwealth's biggest source of climate pollution (see chart below). In 2017, the last year for which detailed data are available, cars and trucks generated 30.5 million metric tons of climate pollution – 42 percent of all the state's emissions.

At the end of December, Governor Baker's administration released a new "2050 Decarbonization Roadmap" report, a long-term plan to virtually eliminate fossil fuel use within the next 30 years, alongside an interim "2030 Clean Energy and Climate Plan," which lays out more concrete strategies to cut climate pollution by 45 percent, relative to 1990 levels, within the next nine years.

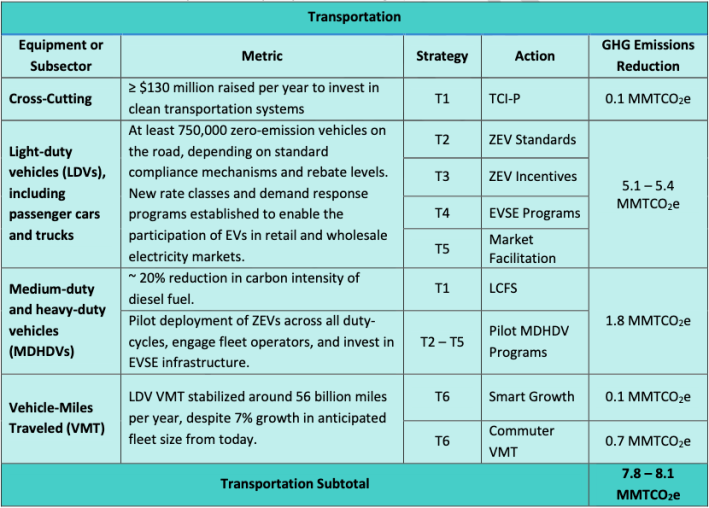

In its plan for 2030, the Baker administration aims to reduce the annual output of climate pollution from tailpipes by 8 million metric tons by 2030 – about 25 percent below present-day transportation sector emissions.

But to get there, the plan focuses most of its attention on subsidizing electric car purchases, and generally dismisses the potential of reducing pollution with transit-oriented development or expanded transit services.

And instead of setting a goal to reduce driving, as several other states have done, the Baker administration's climate plan sets an extremely modest target of "stabilizing" – instead of reducing – light-duty vehicle use over the next decade.

In effect, the plan assumes that the future of transportation looks pretty much like the past, only with battery-powered cars getting stuck in traffic, instead of gasoline-powered cars.

In a a technical report on the transportation sector that informed the broader climate plan, consultants from The Cadmus Group and Evolved Energy Research wrote that

"Reduction in travel demand (measured as vehicle-miles traveled, or VMT), deployment of hydrogen-fuel cell technology, and the use of low-carbon drop-in fuels (such as biofuels), may be helpful... However, due to cost, availability, implementation pace, or technical feasibility limitations, these measures do not appear capable of producing sufficient emissions reductions... to displace widespread electrification of on-road vehicles as the Commonwealth’s primary Transportation Sector decarbonization strategy."

But the same authors largely gloss over the "feasibility limitations" of widespread electric vehicle adoption.

Massachusetts has subsidized electric car purchases since 2014, and to date, the program has spent $37 million to subsidize the purchases of 18,000 vehicles.

"Massachusetts will need to deploy 750,000 to one million ZEVs (zero-emission vehicles) in the next decade," according to the 2030 Clean Energy and Climate Plan.

In their technical report, The Cadmus Group and Evolved Energy Research estimate that hitting that target would require subsidies of at least $4,000 for every new car sold, at a cost to Massachusetts taxpayers of about $880 million a year.

That's roughly 10 times more than the state currently spends to subsidize transit services among the state's 15 regional transit authorities.

Related:

Electric Trucks and Buses Are Coming… Just Not Fast Enough to Save the Climate

The roadmap's near-exclusive focus on replacing gasoline-powered vehicles with new electric vehicles, instead of shifting more travel to transit and other modes, stands in stark contrast to climate action plans from other states.

California, the state with some of the most sophisticated climate policies in the U.S., is aiming for a 15 percent reduction in total light-duty motor vehicle miles traveled (VMT) by 2050 by building more housing in walkable neighborhoods, expanding transit, and increasing fees on drivers.

A November 2020 update to Washington state's climate strategy calls on its Department of Transportation to "make VMT reduction, efficiency, and equity explicit priorities for transportation funding" and calls on the state to tighten up its overall VMT reduction targets, which currently call for a 30 percent reduction in driving per capita between 2008 and 2030.

Even Maine, a rural and transit-poor state, recently set targets to reduce its statewide total light-duty VMT by 10 percent by 2025, and 20 percent by 2030.

The oddities of its transportation recommendations aren't the only challenges facing the Baker administration's climate plans. Shortly after the administration published their strategy, the Massachusetts legislature passed its own "roadmap" legislation that set a more ambitious goal for the coming decade: that the "2030 statewide greenhouse gas emissions limit shall be at least 50 percent below the 1990 level."

The difference between the Governor's and the legislature's targets for 2030 – cutting emissions by 50 percent versus 45 percent – might sound innocuous, but it represents over 4.7 million metric tons of annual greenhouse gas emissions that would need to be eliminated by 2030.

On Thursday night, Gov. Baker vetoed that bill, asserting in his veto message that "the difference between 45 percent and 50 percent means significantly more cost." Legislative leaders have pledged to refile the legislation and pass it with a veto-proof majority in the new legislative session, which has already begun.

The public is also invited to comment on the 2030 Clean Energy and Climate Plan until February 22, via an online form.