As Massachusetts sweats through its first heat wave of the summer this week, a new research paper quantifies something that every pedestrian innately understands: hot, sticky weather makes walks through the city feel longer, to the point where people may opt to take a car for short trips that they'd otherwise make on foot or by public transit.

Back in the cold, dark days of November, Rounaq Basu, then a postdoctoral researcher at MIT, published "Hot and bothered: Exploring the effect of heat on pedestrian route choice behavior and accessibility" in Cities, an urban planning journal.

"I love hiking throughout the year, but summer is when I take a break because it gets too hot for me. So I started thinking about how to incorporate heat into the experience of the pedestrian experience," Basu told StreetsblogMASS (we conducted this interview last November, but have been saving this story for a sweltering summer day when the research would be more seasonally relevant).

Basu's previous research had already examined various aspects of how infrastructure and services influence peoples' travel behavior, so looking at how heat influences those choices was a natural next step.

The key variable whose influence they wanted to calculate was something called the Universal Thermal Climate Index (or UTCI).

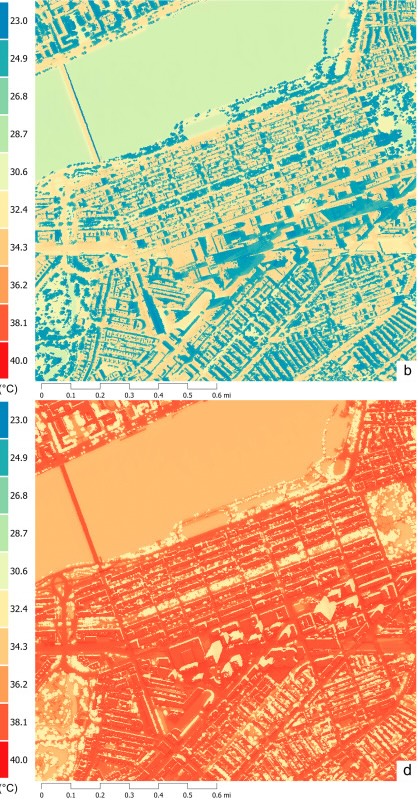

Unlike the temperature or the heat index, which combines temperature and humidity, the UTCI also incorporates wind speeds and radiant temperatures, which vary according the amount of shade and heat-absorbing materials, like hot asphalt.

"The heat index or the temperature are not as appropriate as how people perceive heat when they’re walking," explained Basu. "If it’s 85 and there’s a nice breeze and you’re walking on Commonwealth Ave. through the trees, that feels pleasant, but the same weather conditions can feel oppressive if you're in the middle of a big asphalt parking lot."

Using a dataset of anonymized summertime walking trips from a smartphone fitness app, Basu and his co-authors concluded that pedestrians would choose a route that was, on average, 81 meters longer (about a one-minute walk) if it meant they could avoid a route where the UTCI was hotter by 1 degree celsius.

"What that means is, if I am walking along a street, and there’s a 1 degree increase in perceived temperature, that block is going to feel like a longer walk, 81 meters longer, because it's hotter," explains Basu.

The researchers also found evidence that the effect likely gets more severe the hotter it gets. More extreme temperatures could result in "an exponential increase" in the perceived walking distance.

Basu notes that this isn't merely an issue that affects pedestrians – it also affects how competitive public transit it with car trips.

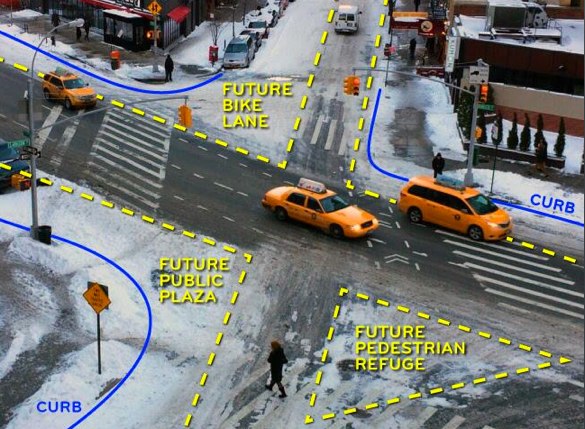

"400 meters (roughly a quarter-mile) is generally considered the reasonable distance to walk to a transit stop. But if you don’t take heat into account, we might be grossly overestimating accessibility – if there's no shade and lots of pavement around, that 400 meter trip might be too much for people to walk on a hot day," Basu observes.

The irony, of course, is that the alternatives – taking a car, or staying home with the air conditioning cranking – are also behaviors that are making our cities even hotter.

Of course, those alternatives aren't available to everyone. Non-white households in Boston are more likely to be reliant on public transportation, and are also more likely to live in neighborhoods that have fewer trees and less shade.

"Heat isn’t always a factor for every single trip people make. There are certain trips that people are making not matter what the heat is like," observes Basu.