After a year in which many systems suspended fare collection because of the pandemic, a growing number of transit administrators, advocates, and elected officials are taking a serious look at eliminating bus fares to make transit more accessible to lower-income riders.

Two bills currently in the Massachusetts Senate would eliminate fare collection on some or all of the state's bus routes.

Senate Bill 1541, filed by Sen. Patricia Jehlen of Somerville, would require each of the state's regional transit authorities (RTAs) and the MBTA to establish pilot programs in which fares are eliminated for some or all of an agency's bus routes.

The Senate Chair of the Transportation Committee, Sen. Joseph Boncore of Winthrop, has filed an omnibus transportation bill that would go even further.

Senate Bill 2315, "An Act Creating A New Deal for Transportation In the Commonwealth," would eliminate fares on all MBTA and RTA bus routes, and compensate agencies for the lost revenue with funding from several new sources, including an increased gasoline tax, increased fees on app-based ride sharing services, and new fees on parking space leases.

Earlier this week, MassBudget, a nonprofit public policy organization focused on racial and economic justice, published three brief papers to make the case for fare-free transit services.

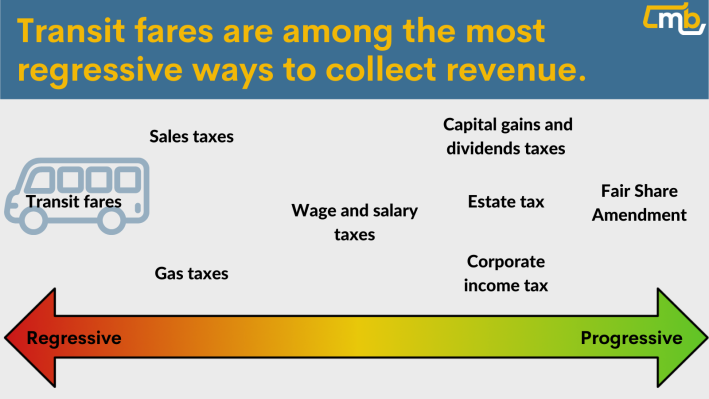

"Transit fares deepen existing income inequalities and racial disparities," argues MassBudget, because the people who pay them generally have lower-than-average incomes, and because fare enforcement is racially biased.

"No fees are collected to enter city parks or libraries, or to attend public K-12 schools, ride a public elevator, use a public garbage receptacle, or report a fire," writes MassBudget policy analyst Phineas Baxandall. "These public services are free, partly as a matter of public right and additionally to encourage their use as a public good."

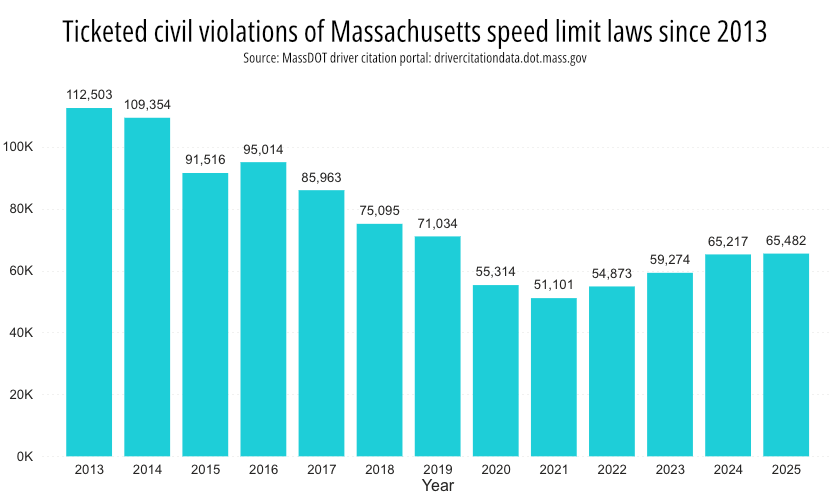

MassBudget argues that because people with lower incomes are most likely to pay transit fares, they amount to a regressive tax – and that replacing them with funds collected from income or corporate taxes would reduce inequality.

Fares are also expensive for agencies to collect. The MBTA's new fare collection system is already overdue and considerably over budget due in part to the complexities of installing a new system on hundreds of buses while also rolling out a massive regional network of vending machines where riders will be able to buy and recharge new payment cards.

There's been particular interest in fare-free buses in Worcester, where the WRTA bus service has been operating without fares for most of the past year.

In a typical year, the WRTA collects a little over $3 million in fares from riders, which cover just over 1/10th of its $26 million total operating budget (the majority of funding comes from state, federal, and local governments). This year, the CARES Act and other relief bills are making up the difference. But that funding won't last much longer.

"We have to pass a balanced budget," Dennis Lipka, the administrator of WRTA, told the Worcester City Council during a virtual meeting of the city's Transportation Committee on Thursday evening.

"If we have to cut $3 million in fares from our budget (without new revenue to replace it), it's going to have to come out of our service," Lipka warned.

For many bus riders, the costs of service cuts, paid in longer waits between buses or missed trips, could be even greater than the current cost of fares. Most fare-free bus advocates agree that agencies would need to be compensated for lost fare revenues with increased funding from local, state, or federal governments.

“The biggest hurdle fare-free buses face is making up for lost revenue," said Sen. Harriette Chandler of Worcester, a co-sponsor of both fare-free bus bills, at Thursday's Worcester City Council meeting. "We have a number of paths we can take, but we must take into consideration where the money is coming from, and whether it’s sustainable in the long term.”