Earlier this fall, GBH News and PRX launched "The Big Dig," a nine-episode podcast that tells the history of Boston's turn-of-the-century highway expansion that became the most expensive road project in the nation's history.

15 years have gone by since the Rose Kennedy Greenway finally hosted a formal grand opening ceremony to mark the project's substantial completion.

Ian Coss, the producer and host of The Big Dig podcast, grew up with the construction project, and thinks that now is a good time to re-appraise a project that's frequently remembered as a massive boondoggle.

"So much ink was spilled and harsh words spoken about this project when it was being built, but now the fog of war has lifted, we can take it in in its full scope, in a way that I don’t think we could have at the time," says Coss. "And it’s recent enough in the past that most of the people who are at the center of the story are still alive."

StreetsblogMASS talked with Coss about his podcast in a Zoom call last week. The following is a transcript of that conversation, edited for length.

StreetsblogMASS: Why you think this story is relevant right now, so many years after it finally finished construction?

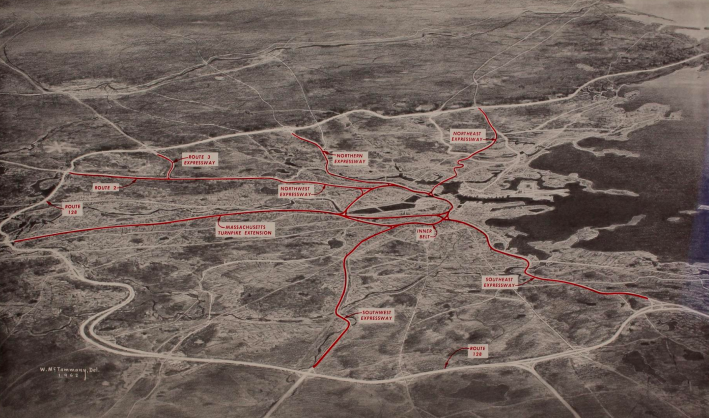

Coss: It’s basically a 40-year story, going from about 1966 to 2008. If you’ve ever read The Power Broker, the legendary biography of Robert Moses, part of what’s so compelling about that book is that it gives you a half-century of understanding the way things got built, from about 1910 to about 1960.

And the Big Dig story picks up exactly where that book left off, with the next 50 years – the end of the interstate highway era. The rise of the environmental movement, the sort of epochal shift towards smaller government, privatization, Reaganomics, the end of the bipartisan consensus around highway-building and infrastructure.

I make the argument that if you want a case study for the challenges of building a big infrastructure project today, I don’t think there’s a better case study than the Big Dig – even if what you’re interested in building is a rail extension or green energy.

StreetsblogMASS: The Big Dig’s legacy as a transportation facility is pretty ambiguous. It did not solve traffic; it saddled the MBTA with a lot of debt and made promises for transit projects that never got built. I’m really curious about Fred Salvucci’s perspective on it in hindsight (Salvucci is featured prominently in the podcast's early episodes as a major figure in the highway revolts of the 1960s, and as the Big Dig's primary champion in the 1980s). Did he ever reveal any second-guessing about whether this project was really worth it?

Coss: It’s fundamentally a highway expansion, and the thinking around that has obviously changed since the project began. One argument I would make is that it’s still a relevant case study, even if what you’re interested in building is a rail extension or green energy – the lessons are applicable broadly whether or not you want to build highways.

Part of what’s interesting about this story taking so long, from the late 60s to the 21st century, is that the vanguard of what’s conceivable for American cities moved so far in that time.

If we try to put ourselves in the mindset of 1972, the idea of tearing down the Central Artery and not replacing it was unthinkable. Fast forward to today, and there are cities contemplating that kind of highway teardown.

At some point I asked Fred if, with the hindsight he has now, would he consider that. But he really stands by the legacy of this project as a transportation facility. Obviously, he was as frustrated as anyone that the transit commitments weren’t built, and he will rail to this day about the subsequent administrations that did not pursue the Green Line Extension or the Red-Blue connector and other projects.

Fred is a very practical strategic thinker. He always understood that they could not tear down the elevated Central Artery unless they replaced it somehow. And they could not get that project done if it did not also build the third harbor tunnel (the Ted Williams I-90 tunnel). These things were politically intertwined.

So I think he would stand by those choices, if the alternative was – the alternative they were facing was to patch up (the existing elevated artery) as best they could, or potentially even widen it.

If we still had the elevated Central Artery today, and we had $15 billion of unrestricted funds to spend, I’m sure that Fred and others could imagine a more radical version of this project. Maybe including a north-south rail link, for example. I’m sure that the surface would be treated differently – I know Fred Salvucci has a lot of frustrations with how, as wonderful as the Greenway is in many respects, there are a lot of lanes and highway ramps.

My hope is that the complexity of it comes through – I don’t intend for the series to be like, "rah rah, build big things, build big no matter what." My hope is that the first two episodes (about the 1960s and 1970s highway revolts) provide a compelling case for why there are checks and balances.

But then I hope that the later episodes reckon with the fact that those systems we’ve put in place, like the environmental impact statements and community input and legal challenges – that those things do have costs too. And it is a lot harder to do big things than it was in the 1960s.

In this moment, part of the reason I want to tell this story is because the politics of building has really changed in the past decade, because of climate change and the housing crisis. If we rewind a couple decades, the left, in many respects, was trying to stop things from getting built. But now, building means wind farms and affordable housing. There’s a lot of urgency to build quickly and ambitiously. So this is a really interesting moment to reckon with the last half-century in which we have deliberately made it more difficult to build big things. And the Big Dig captures a lot of the promise and peril of building big things.

StreetsblogMASS: What was the most surprising thing you learned in the history of this story?

I’d had no idea that the Big Dig came out of Boston's anti-highway movement… As someone who just grew up as a casual observer, that was never part of the lore of the Big Dig as I grew up with it. So that was a revelation.

The project emerged out of this radical moment where things that had been unthinkable were being thought and said and enacted. And it really embodied the idealism of that moment.

Other surprises – the fact that Mitch McConnell voted to override Ronald Reagan’s veto on the Big Dig spending bill? That was pretty good. Newt Gingrich also voted to override that veto. That was a different time (Coss covers the Congressional horse-trading that financed the Big Dig project in the podcast's third episode).

StreetsblogMASS: The most striking detail of that episode was how Congress sacrificed the 55 mph federal speed limit to get this bill passed. As someone who writes a lot of about street safety and crashes, that made me want to tear my hair out. So many people have died and been injured because of more dangerous highway speeds since then (a 2009 academic study estimated that there had been 12,545 deaths from highway crashes that were attributable to the repeal of the federal 55 mph speed limit between 1995 and 2005).

It feels like the kind of thing that probably would have happened at some point – a lot of lawmakers wanted it, and after the oil crisis ended there was less political will to keep (the 55 mph speed limit) in place. But you can not separate that decision at that time from the Big Dig vote.

There’s more audio that we had of Ryan Donnelly, a congressman from Massachusetts, talking about Jim Howard, that congressman from New Jersey (who wanted to keep the 55 mph speed limit in place).

This clip did not make it into the final version, but he was essentially saying, whatever Jim Howard wanted to make the speed limit, Massachusetts would vote for it, because we needed Jim Howard so desperately to get the Big Dig funding.

But when it became clear that that’s what the Senate wanted to change, in order to include the Big Dig funding, he gave it up.

StreetsblogMASS: You've released up to episode 7 so far – can you give us a taste of what's going to be in the last two episodes?

Episode 8 is about the ceiling collapse in the tunnel in 2006, and more broadly, it’s about the engineering failures in the project and how we think about accountability for those. For anyone following the Green Line Extension problems right now, I think that episode is very relevant.

Episode 9 is the final episode; it's sort of an epilogue set in the present day. It speaks to some of the questions you were asking, whether this really was the best idea? What has it done for the urban fabric of the city? What has it done for traffic? And what has it done to our capacity to pursue big projects?

StreetsblogMASS: We’ve recently been writing about MassDOT’s role in the climate emergency. We're at a point where highways are now the biggest source of air pollution in the Commonwealth, but MassDOT doesn’t really have a credible plan to meet the state’s climate targets. They are still pursuing big highway projects, but there's increasing doubt about whether those projects are compatible with a future where we're able to survive the climate emergency.

I guess I do believe that the solution, any solution to the climate emergency does involve building. This is not a crisis that we can wean ourselves away from – it’s not just about turning off your lights and riding bikes and growing food in your backyard – all of which are things that I do do personally, but the scale of the problem is much bigger. We will have to build our way out of this hole.

Regardless of what we want to build, this is an important case study in that regard. The Big Dig is totally a creature of its time. It had to fit within the funding framework of the interstate highway program, that was, and really remains the only national infrastructure investment program… It is a weird creature of its time, a highway project that was struggling to not be a highway project but ended up being the largest highway project in history.

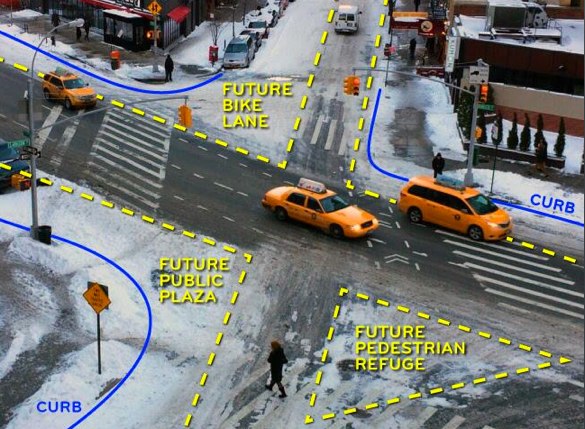

I was at City Hall recently and talking with some of the staff there, and they told me they couldn’t imagine doing something like this today. When trying to take away a single parking spot to put in a bike lane drags out to like a year-long process. And so the idea of tearing down an expressway and putting it underground to put in a greenway – the scale of this project feels unimaginable.

We do need to remind ourselves that big projects are possible. Whether it’s a big offshore wind project, or north-south rail, or east-west rail – it will take time and perseverance, but we are capable of these things.