It's been two years since planners nailed down a consensus for a new alignment for the Massachusetts Turnpike in Allston.

But as the project enters its next phase of planning, another conflict is brewing over the design of the new surface streets that would serve the new neighborhood that's expected to grow across the district's 90 acres of empty land.

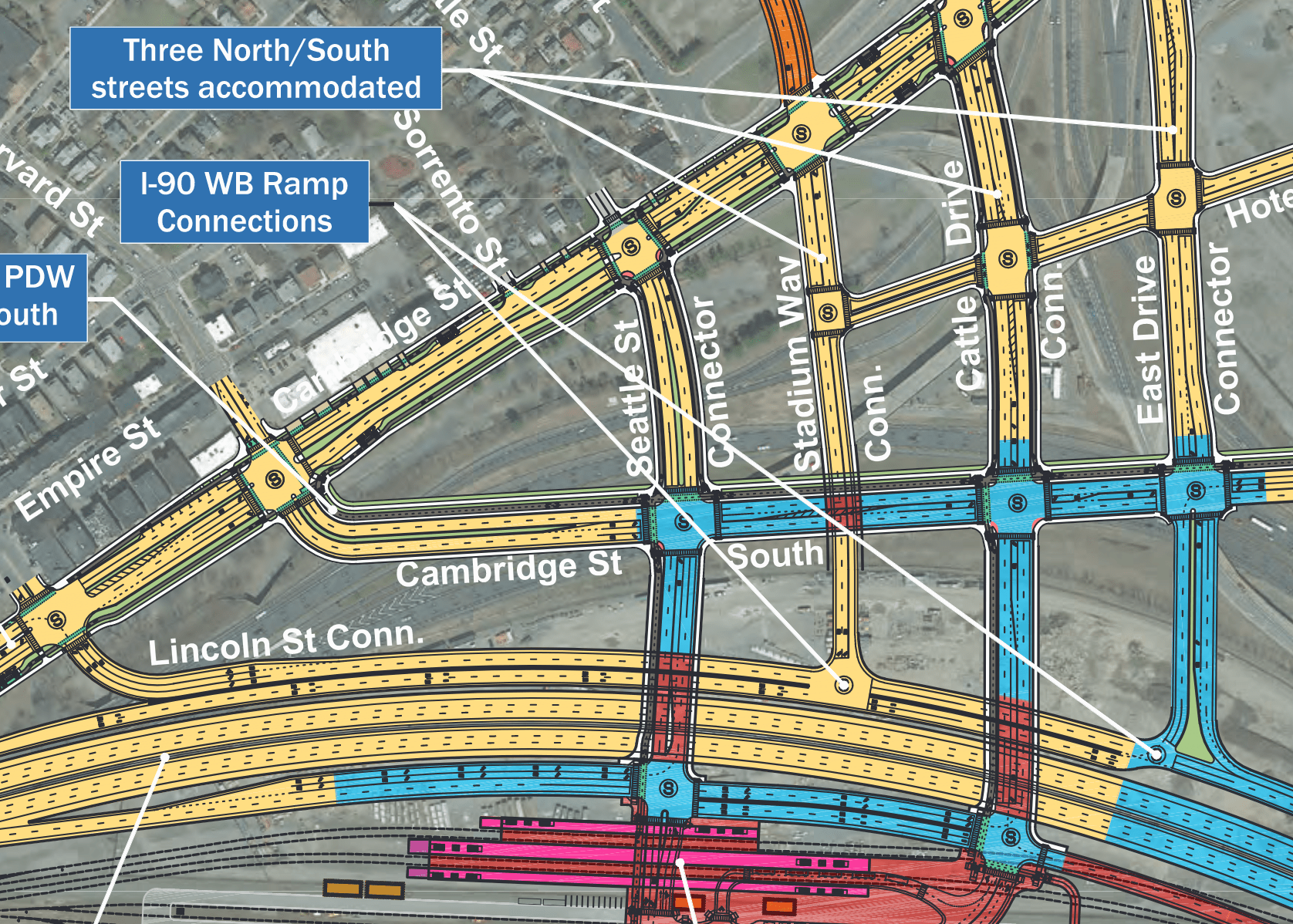

For years, MassDOT – the agency in charge of the project – has been proposing to build those streets as a grid of massive 5-lane feeder roads, two to three times wider than any of the streets in the adjacent neighborhoods (see plan above).

Local officials from the cities of Boston and Cambridge, along with most neighborhood residents and transportation advocates, are pushing back against that vision.

They'd like smaller, safer, less expensive streets that would support a new high-rise district of transit-oriented development instead of inviting traffic jams.

“There hasn’t been much of a focus yet on the massive size of the adjacent intersections that are being proposed here," said Brendan Kearney, co-executive director of WalkMassachusetts, at a November 14th meeting of the project's advisory task force (editor's note: Kearney is also a volunteer member of the StreetsblogMASS Board of Directors). "Those would certainly be a major concern for us.”

Later in the same meeting, Chris Osgood, Boston's former Chief of Streets and now the Senior Advisor for Infrastructure for Mayor Michelle Wu, seconded Kearney's concerns.

"Right-sizing the roadways so they really feel like neighborhood streets... is a top priority for the City of Boston,” Osgood told MassDOT's project team.

The conflict boils down to a fundamental disagreement over what the primary function of those new streets should be: public spaces for a walkable, transit-oriented urban neighborhood, or a grid of freeway off-ramps designed to accommodate overflowing traffic jams from Interstate 90.

MassDOT cites federal rules for current design

Speaking on background, MassDOT officials have told StreetsblogMASS that the agency's current designs for multi-lane connector roads are being proposed in deference to rules from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA).

The Turnpike is part of the federal Interstate highway system, and FHWA regulations require that the new interchange must be able to "safely and efficiently collect, distribute, and accommodate traffic on the Interstate facility (and) ramps."

Traffic models from the Central Transportation Planning Staff of the Boston Metropolitan Planning Organization – typically referred to as CTPS – have predicted that thousands of car trips will fill up these new streets in the future, when the district's empty land will be filled with new high-rise developments.

By MassDOT's reasoning, if those new streets leading away from the Turnpike aren't wide enough, there's a risk that traffic congestion could back up onto the interstate highway, in violation of FHWA's regulations.

“We’re hopeful that the latest and greatest CTPS modeling will have a much better job of capturing transit's share, and if, wherever we can, we can reduce the cross-sections (of the streets), we will do it," said project consultant Mike Hall of Tetra Tech at November's task force meeting. “We’ve been trying to achieve that as we go along, and we’ll continue to work, to do our best to minimize the cross-sections of these roads.”

Models predict one thing; experience predicts another

Members of the Allston project's task force have countered that we don't really need a model to predict what will happen if MassDOT builds wider roads in Allston, because it's a strategy that state transportation agencies have been pursuing for a century, with an breathtakingly consistent record of making everything worse.

During a 2017 task force meeting, when CTPS was preparing traffic projections for an earlier iteration of the project, Bill Deignan, the City of Cambridge's Transportation Program Manager, suggested that CTPS's models incorporate anti-transit biases that render their predictions all but worthless in walkable neighborhoods.

"Are we going to rely on modeling to tell us what has to happen, or are we going to build the future that we want to see?" asked Deignan, according to the minutes of the December 2017 task force meeting. "The CTPS model is crazy. It is not a multi-modal model. The traffic numbers that it shows for Cambridge often just don’t make sense."

Six years later, at the November 2023 task force meeting, Allston resident and task force member Jessica Robertson echoed Deignan's criticisms.

"The state has ambitious mode shift and climate goals, and all of these things that were not really reflected in the model last time (in 2017)," observed Robertson. "There was an assumption that there would just be an ever increasing amount of vehicle trips, at some constant rate forever into the future, which is directly counter to state policy.”

To Deignan's point, the City of Cambridge has successfully removed numerous motor vehicle lanes from former multi-lane roadways around Kendall Square in recent years, even while development in the neighborhood has added millions of square feet of new buildings.

Meanwhile, the new "Big Dig" surface streets that were built above Interstate 93 in downtown Boston and around I-90 in the Seaport district were designed to FHWA specifications, based on CTPS predictions.

In those districts, wide multi-lane surface roads funnel huge volumes of vehicles in and out of the interstates – which are reliably clogged with stop-and-go traffic.

Extra lanes diminish space for housing, academic space

It might be too gauche for a institution with a $50 billion endowment to discuss in public meetings, but MassDOT's proposed multi-lane roads also eat up a significant amount of Harvard University's real estate – land where the university would otherwise like to build a new transit-oriented high-rise district of housing, academic buildings, and lab space.

On nine acres of vacant land it owns nearby on Western Avenue, the University recently won planning approval for a complex of high-rise buildings with 345 new homes, more than a half-million square feet of commercial spaces, and a large conference center.

All that new development will be served by a loop of modest two-lane streets around its perimeter.

Under Harvard's long-term plans, those streets will eventually become part of a new street grid. Two one-block segments of new streets under construction now – Cattle Drive and East Drive – will eventually extend south to connect to the Massachusetts Turnpike through the Allston Multimodal Project area.

Under MassDOT's current plans, those two streets would abruptly bloat from two lanes to 4- and 5-lane cross-sections south of Cambridge Street, where Harvard owns roughly 90 acres of mostly-vacant land.

Subtracting just one lane from those streets and several others in the web of multi-lane roadways in MassDOT's current plans would give Harvard several additional acres of real estate to build on – enough to fit hundreds of additional new homes into the neighborhood.

Read more StreetsblogMASS coverage of the Allston Multimodal Project here.