After a full decade of planning, the Commonwealth's various transportation agencies are still far away from a consensus on how it will rebuild the sprawling Interstate 90 highway interchange in Allston – but they are beginning to show some willingness to reduce the overall footprint of the project's sprawling infrastructure.

As we've reported previously, fundamental details of the project – like whether the project will include a multi-acre storage facility for MBTA trains, or how to rebuild the highway without major disruptions to the region's passenger rail services – remain up in the air.

The project also faces a funding shortfall that's measured in the hundreds of millions of dollars, while the prospects for additional financial assistance from Washington have all but disappeared.

The state says it still intends to file its federal Environmental Impact Statement – a key document that will nail down the conceptual design – within the next year.

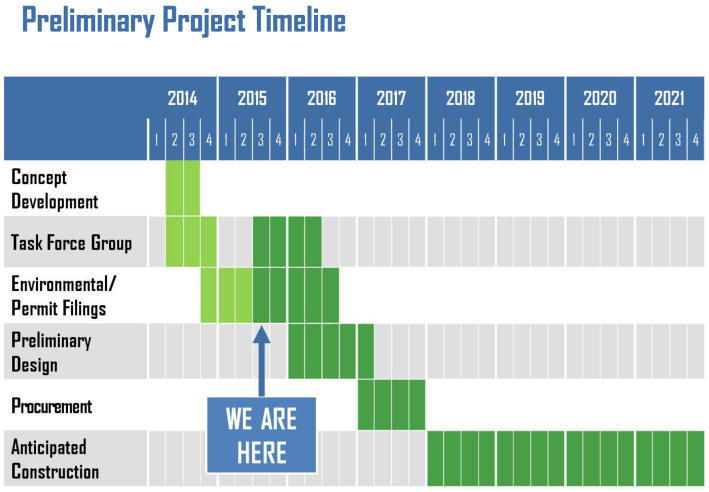

But project managers have been making similar promises for over a decade (the timeline at right came from the eleventh meeting of the project's citizen task force, which was held in July 2015).

A nine-figure budget shortfall

One fundamental problem with MassDOT's current design for the Allston Multimodal Project is its projected cost, which far exceeds its available funding.

To date, the Commonwealth has cobbled together about $1.75 billion in pledges for the project, more than half of which would come from Massachusetts taxpayers.

That's about $165 million short of MassDOT's 2022 cost estimate for the project, which was $1.9 billion.

The real shortfall is probably much larger. That $1.9 billion estimate is three years old, and predates a historic spike in costs for construction materials.

Since 2022, USDOT's Highway Construction Cost Index has surged by 25 percent – far outpacing the rate of inflation in other sectors. Accounting for inflation with the USDOT's index, the true cost of the Allston Multimodal Project in 2025 would be closer to $2.4 billion.

Shrinking expectations

At the March 12 meeting of the Allston Multimodal Project's task force, discussion focused on one particularly controversial aspect of the project: a multi-acre layover yard for train storage.

Many transit advocates and Allston residents have objected to the idea of building what was effectively a massive parking lot for diesel trains in the middle of what is supposed to become a new transit-oriented neighborhood.

Their cause appeared to gain momentum in early 2024, when MassDOT Secretary Monica Tibbits-Nutt said "the layover's gotta go."

But the MBTA, Amtrak, and MassDOT rail planners have been pushing back, citing the need for new trains (and train parking) to realize their plans for increased regional rail service and new intercity services with MassDOT's Compass Rail initiatives.

At the March 12 project task force meeting, MassDOT and project consultants from VHB presented a new analysis that concluded that the state badly needs more space – including Allston – to park its growing fleets of passenger trains.

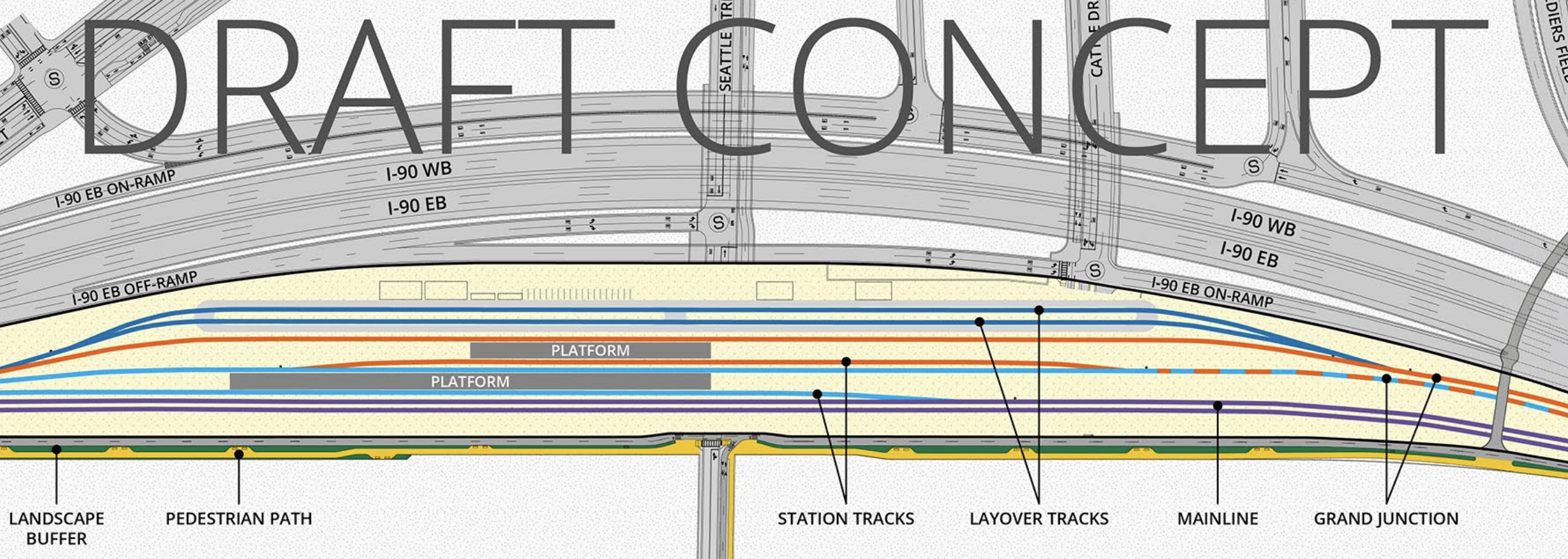

In gesture of compromise, they presented a revised plan for West Station with a smaller layover yard, with two tracks instead of four (see the diagram at the top of this post). The new plan also added an additional "express" track that bypasses West Station altogether (the previous design had proposed only one bypass track).

Task force representatives from Harvard University and the City of Boston – two institutions that have pledged critical stakes in the project's construction financing – still urged MassDOT to analyze alternative, less expensive layover sites elsewhere in the region to support its rail service plans.

“What are we giving up by placing a rail yard within this area where we’re creating a new neighborhood, one that could certainly use additional housing?" asked Albert Ng, Harvard University's representative on the project task force.

Former MassDOT Secretary Fred Salvucci, whose widowed grandmother lost her home in Brighton when the Commonwealth seized and bulldozed her house to build Interstate 90 in the 1960s, was more blunt.

"This community got screwed when the Turnpike was built. They got screwed when the CSX (rail) yard was there. We spent a lot of time trying to get the yard out, and we’ve been talking (about it) since the administration of Deval Patrick," said Salvucci. "This is going backwards. It’s going back on people who have been led to believe that this would be a great mending of the scar through our community."

The bigger barrier

No matter what West Station eventually looks like, its size and its costs will be minuscule compared to the impacts of the two expressways – Interstate 90 and Soldiers Field Road – that MassDOT is still planning to demolish and rebuild through the project area.

But financial, legal, and environmental constraints might force the state's transportation officials to reconsider the 20th-century assumptions behind their previous designs for those roadways.

The path forward for MassDOT's highways in Allston might also be getting narrower – we'll write more about that in an upcoming story.