The Grand Junction bridge certainly doesn't look like an important piece of infrastructure: it's caked in rust and graffiti and half of it has been abandoned, such that when you're looking down on it from the B.U. Bridge, you can peer straight through its steel lattice structure and see the Charles River below.

But don't let its appearance deceive you: this bridge is a critical link in the regional rail system. It's the only rail connection within 40 miles of Boston that links the otherwise disconnected north and south sides of the MBTA's commuter rail network.

The MBTA's main commuter rail maintenance facility, the Boston Engine Terminal, is located 2.5 miles northeast of the Grand Junction bridge, in East Somerville. Anytime a train on the south side needs repair work, it uses the Grand Junction line to get to the shops on the north side.

Similarly, Amtrak's Downeaster trains, which operate out of North Station, rely on the Grand Junction connection to access Amtrak's Southampton Street maintenance facility in South Boston.

Under current construction plans for the proposed Allston Multimodal Project, a $2 billion reconfiguration of the Massachusetts Turnpike and Soldiers Field Road, the southern abutments of the Grand Junction Bridge on the Boston side of the river would be demolished to make room for 12 new lanes of riverfront highway.

Several years later, when the road work is substantially done, contractors would then reconnect the Grand Junction with a new rail viaduct that could potentially carry a new transit connection between Boston and Kendall Square.

But officials from Amtrak and the T are throwing cold water on that plan.

At an August 21 working group meeting for the Allston Multimodal project, MBTA officials warned that if the highway project severs the Grand Junction link, "MBTA service would cease within weeks, due to an inability to conduct required maintenance."

Alternatives are impractical, expensive

There are alternative options for the T to continue maintaining its trains if the Grand Junction were cut off, but they would impose considerable costs on an agency that's already strapped for cash and resources.

One option would be for the T to take its trains on a detour deep into central Massachusetts, where there's another north-south rail connection. That detour would require the T to send its south side trains all the way out to Worcester, then north on a freight railway connection to Ayer, than back into Boston via the Fitchburg Line to access the Boston Engine Terminal maintenance facility in East Somerville.

That's a 103-mile detour for a trip that's currently just 2.5 miles.

In a presentation to stakeholders in the Allston Multimodal Project, MBTA officials said that that detour "is not feasible for the MBTA’s maintenance needs."

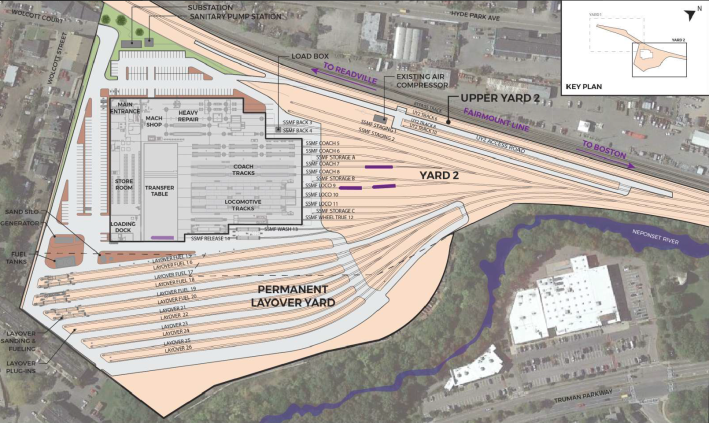

The other option is for the T to build a new maintenance facility specifically for its south-side trains. And in fact, the T has already started preliminary design work for a new maintenance facility and train storage yard in Readville, at the end of the Fairmount Line.

Although the T has set aside $5 million for early design and environmental permitting work, there's currently no money available for the agency to actually build this facility.

In 2020, former MassDOT Secretary Stephanie Pollack said that the project could cost approximately $300 million; with high rates of construction cost inflation in the four years since then, the cost today might be closer to $400 million.

Who would pay for the project is also an important consideration. The T is still struggling to repay debt associated with the Big Dig highway project in the early 2000s; forcing the cash-strapped agency to borrow another $400 million to benefit yet another highway megaproject will be a politically heavy lift.

"Regional rail electrification projects will be delayed by use of financial resources and real estate on these diesel projects."

There's also the question of timing. Some advocates and MBTA officials have suggested that new layover yards and a new South Side Maintenance Facility ought to be designed for a future fleet of all-electric trains.

That won't happen if the MassDOT forces the T to finish the new maintenance facility before it has a chance to electrify all of its rail lines that run out of South Station.

"With loss of access to BET (Boston Engine Terminal), many of these facilities need to be geared towards the needs of the MBTA’s current diesel fleet, instead of future fleet electrification," MBTA officials warned stakeholders in the August 21 meeting. "Regional rail electrification projects will be delayed by use of financial resources and real estate on these diesel projects."

A third option: MassDOT takes responsibility

It's not clear whether any stakeholders ever discussed it at August's meeting, but there is a third possible solution to this dilemma: MassDOT could require future construction contractors working on the Allston I-90 project to keep the Grand Junction rail connection open until a replacement bridge is ready.

That option would likely complicate the project's construction logistics in a notoriously tight site on top of the Charles riverbank, and add to the multi-billion dollar price tag for MassDOT's highway proposal.

But given the alternatives, MassDOT's highway builders might just have to take responsibility for the disruptions they're creating, instead of piling on more debt and more problems onto the region's transit riders.