The Worcester Regional Research Bureau, an independent nonprofit public policy organization, has published a new report calling on Worcester's regional transit agency, the WRTA, to eliminate fare payments on its buses, arguing that the public benefits of dramatically increasing transit ridership would outweigh the agency's financial costs from lost fare revenue.

The WRTA collects about $3 million a year in fares from its 23 fixed routes and from its paratransit services. That revenue only covers about 14 percent of the agency's operating expenses, and has declined in recent years along with ridership.

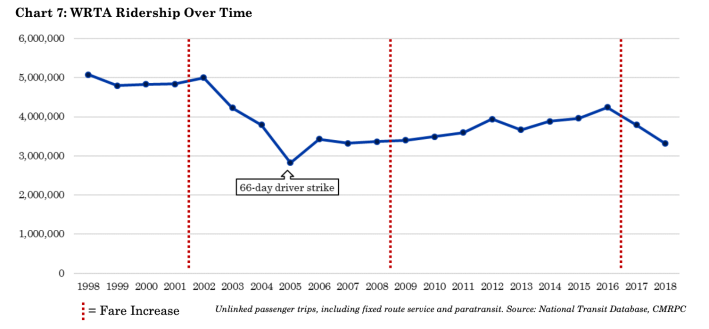

Collecting those fares is expensive: the Research Bureau estimates that maintaining fareboxes and administering fare sales costs the agency about $850,000 every year, such that the net gain to the agency is closer to $2 million, or about 10 percent of the agency's operating budget. The WRTA's riders are also particularly cost-conscious: when the agency raised fares by a quarter in 2017, from $1.50 to $1.75, it witnessed a sharp decline in ridership:

Given how fares offer only a relatively minor contribution to the WRTA's bottom line and seem to prevent some regular customers from riding as much as they'd like to, the Research Bureau report concludes that the agency is "a perfect candidate for a fare-free system."

“A lot of the initial reaction to this idea is focused on the lost fare revenue," said Tom Quinn, the report's lead author, in a phone interview. "But the bigger problem (for agencies) is that buses are late or unreliable. Especially when customers pay with cash, that takes time… Washington D.C. did a study of their metro system, and found that cash payments are 12% of transactions, but they take up 24% of boarding time.”

Boston City Councilor Michelle Wu has floated a similar proposal for the MBTA. But to make it happen, the T would need to figure out a way to replace the $694 million it collects in fare revenue – an amount that covers almost half of its operating budget.

As a smaller system, the WRTA would have a much more manageable gap to fill.

Dennis Lipka, the administrator of the WRTA, says that the agency is currently shopping for new, next-generation fare collection systems, and going fare-free will be one of the options they consider.

But Lipka also believes that a new, cashless fare collection system could address most of the issues with fare collection that Quinn's study raises.

"The current fare collection system we have is the same one being used by the MBTA. The patch-ons and adjustments to it over the years have taken it way beyond its capacity, and it’s a poor piece of technology," says Lipka.

The current fareboxes frequently malfunction, which means that many riders actually do ride for free, albeit on an unpredictable basis. "If we had a good system, with our current ridership, we could collect between $5 and $5.2 million in fares," says Lipka – enough to cover a more substantial 19% of the agency's operating budget.

Lipka also believes that a next-generation fare payment system could offer some of the same operational benefits as a fare-free system, with less time lost waiting for riders to fumble for change. And he would have more flexibility to offer discount programs, which are currently limited by the mechanical constraints of the buses' farebox equipment.

"We could have much more flexibility in how we charge for rides and manage discounts. We could incentivize people to ride earlier in the morning or later in the afternoon with off-peak fares. We could offer student passes to schools and colleges.”

Both Quinn and Lipka agree that growing ridership, and maximizing the capacity of the WRTA's buses, is the fundamental goal. Eliminating fares will attract more riders, but only if the agency can balance its budget and keep its buses running.

"We didn’t want to put anyone in a corner and specify where they should get that revenue," says Quinn. "But there are a lot of great ideas from other cities: increased city aid, state aid, philanthropy or the business community."

The report makes the case that the public value of a free transit system extends far beyond the financial considerations of lost fare revenue: reduced greenhouse gas emissions, reduced congestion in the local road network, and improved equity and access for lower-income residents.

If those are things that the city of Worcester and its leading institutions are willing to pay for, then free transit could be a bargain for everyone.