Filling in the remaining gaps in the east-west Mass. Central Rail Trail, which is envisioned as a 104-mile path from Northampton to Boston, could generate over $200 million a year in increased economic activity from new trail-oriented tourism, according to a new analysis.

The report, commissioned by the Norwottuck Network, a nonprofit dedicated to completing the trail, estimated that a continuous off-street connection between the Connecticut River Valley, central Massachusetts, and the Boston region could attract 4 to 5.5 million visitors every year.

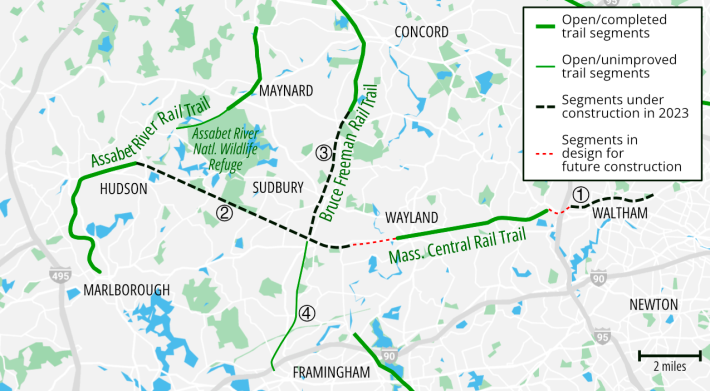

Existing segments of the Mass. Central Rail Trail (MCRT) include about 55 miles' worth of accessible rail trail, including the newly-opened Somerville Community Path between East Cambridge and Davis Square.

Another 11 miles of new trails along the MCRT corridor are currently under construction. Plans are in the works to fill in the remaining gaps in eastern Massachusetts – in Belmont, Waltham, and Wayland – within the next 5-7 years.

But through more rural areas of the state, large gaps still remain, especially in the hilly terrain of central Massachusetts.

Comparable trails generate significant rural tourism

The study's authors compared the MCRT to two other completed long-distance rail trails: the 150-mile Great Allegheny Passage, which runs from Maryland to Pittsburgh, and New York's 300-mile Erie Canalway Trail.

A 2021 study of the Grand Allagheny Passage concluded that that trail generated $121 million in additional spending associated with trail tourism.

"Compared to shorter shared use paths, the longer trails attract many more users who are not local and travel from far away," wrote the authors of the Massachusetts report. "These visitors often stay overnight along the trail and spend substantially more than other users on lodging, food, and equipment rentals."

Craig Della Penna, the Board President of the Norwottuck Network, told StreetsblogMASS that a completed MCRT would be especially impactful in the rural communities of central Massachusetts.

"There are environmental justice communities like Gilbertville, which is a completely intact Civil War-era industrial village frozen in time. These are places that have been forgotten by the rest of the state, where being connected to the trail would be a big deal," Della Penna said.

Significant health savings

The report also made high-level estimates of how improved bike and pedestrian infrastructure could improve health outcomes for people living near the trail.

Based on survey data, the report's authors estimated that 1,750 people meet federal guidelines for physically active lifestyles because they have access to existing segments of the MCRT.

Completing the remaining gaps of the MCRT, they estimate, would give thousands of additional people the opportunity to incorporate physical activity into their daily routines, and save $6 to $7.7 million a year in reduced health care expenses for trail users.

Report does not include transportation benefits

Notably absent from this report's $200 million tally of annual economic benefits: the potential savings from trail users who might be able to replace car trips with walking or biking trips.

The report's authors chose to focus on health benefits and tourism spending, but the benefits from reduced congestion and driving expenses, plus improved air quality, could be significant.

"Currently, 7 percent of Massachusetts residents live within one mile of an existing segment of the MCRT," wrote the report's authors (this was written before the opening of the Somerville Community Path extension).

If the MCRT were completed in conjunction with major intersecting north-south trails like the Bruce Freeman Rail Trail to Lowell, the Columbia Greenway through Westfield, and the Twin Cities Rail Trail to Leominster, the report's authors estimate that nearly one in four Massachusetts residents would live within a mile of a cross-state rail trail network.

Taxpayers get strong returns on trail investments

Della Penna acknowledges that the remaining gaps in the MCRT include some of "the really expensive parts," with trail segments that must detour around active rail lines or replace missing bridges.

In 2020, the Commonwealth completed a feasibility study for filling in major gaps in the trail's central section, but the report refrained from making cost estimates.

The 2.8-mile segment of trail that's currently under construction in Waltham has a construction budget of about $9 million, or about $3.2 million per mile.

That project is in an urban location with numerous street crossings, so it's not an ideal comparison for trail projects that would be built in more rural areas of the state.

But using the Waltham project's per-mile costs as a rough proxy, it might cost the state $176 million to build the remaining 55 miles of trail between Belchertown and Belmont.

According to the Norwottock Network's study, the investment would pay for itself in under a year.

"The $200 million figure is a conservative estimate – it doesn’t factor all the potential benefits. But that’s the big deal here... we’ve been putting in a lot of work over the last 30 years, so where are we going now?" asks Della Penna.