Last week, Governor Healey's administration announced a modest initiative to help address the state's dire housing shortage by offering 450 acres of surplus state-owned land for potential housing development.

The properties include a former almshouse and state hospital campus in Monson, an abandoned reform school in Lancaster, and the old state prison in Concord.

The administration estimates that the land could support the development of 3,500 new homes across the state.

But one of the state's biggest landowners is conspicuously absent from the effort.

MassDOT's Highway Division controls thousands of acres of land across the Commonwealth. Its landholdings are so extensive that a spokesperson admitted to StreetsblogMASS that the agency has no idea how much land it owns.

We can hazard a guess: according to the agency's road inventory, MassDOT controls about 9,500 lane-miles of paved roadway. Assuming an average lane width of 12 feet, that amounts to over 600 million square feet of asphalt, or almost 14,000 acres.

To put that figure into context, the Commonwealth's biggest state park, the Mount Greylock Reservation in Berkshire County, encompasses 12,455 acres.

Notably, this estimate does not include any additional right-of-way that the agency controls in highway medians, shoulders, rest areas, and cloverleaf highway interchanges, like the one we wrote about earlier this year in the tiny Cape Cod town of Truro.

MassDOT's contribution to the housing crisis

During the peak highway-building decades of the mid-twentieth century, the state seized and destroyed thousands of homes across the state – particularly in working-class and racially diverse neighborhoods like Roxbury and Chinatown in Boston and the North End of Springfield.

There's no detailed accounting of how many homes highway engineers destroyed to make way for roads like Interstate 93, Interstate 91, the Massachusetts Turnpike, and I-290 through the middle of Worcester. Highway projects were frequently a component of broader "urban renewal" projects that laid entire neighborhoods to waste.

Worcester's population declined by 20 percent during the peak decades of urban renewal and highway construction, between the 1950 and 1980 censuses. Boston's population lost 238,450 residents – a 30 percent decline – in the same period.

Today, many of those highways are nearing the ends of their useful lives. State transportation planners have acknowledged that several of them are functionally obsolete, and could function just as well, or better, with a slimmer footprint and fewer lanes.

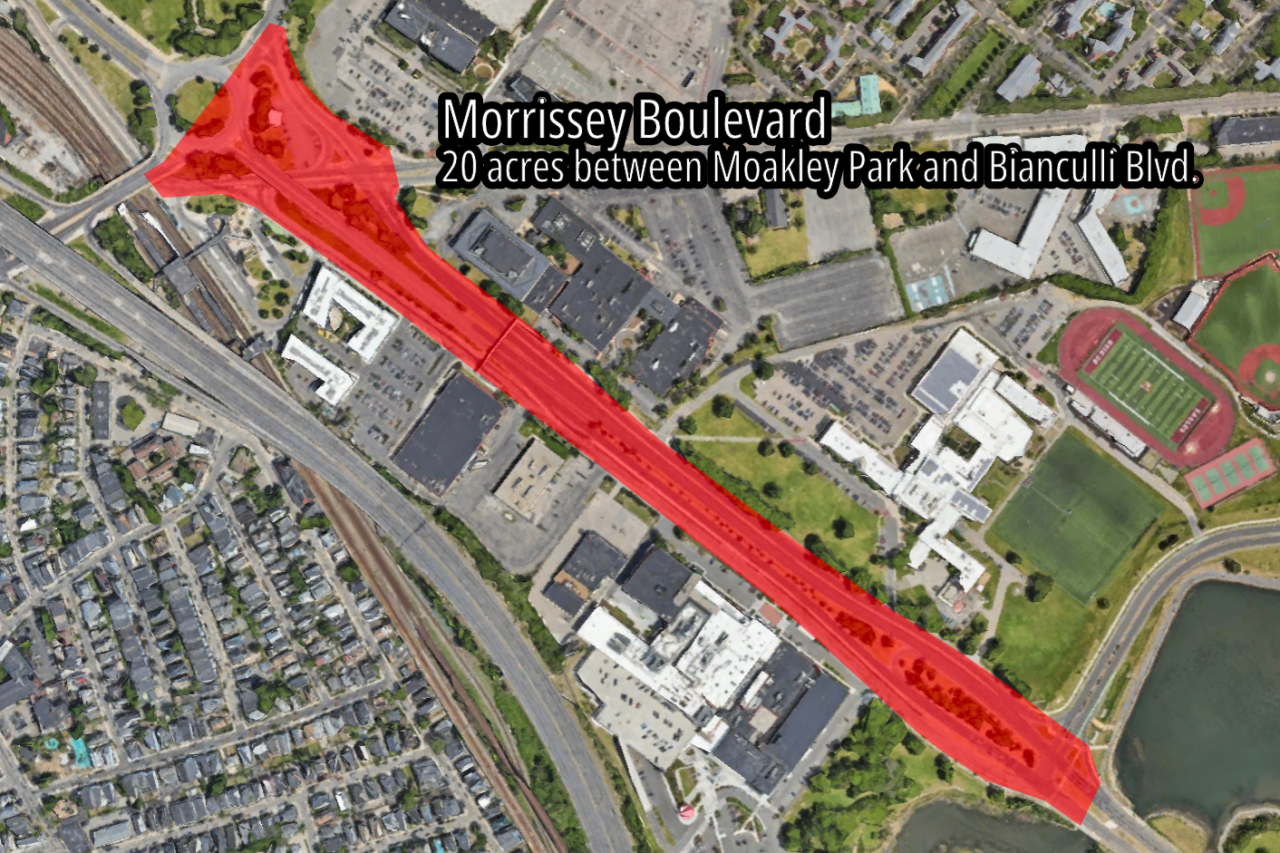

Many of the sites being offered under Governor Healey's State Land for Homes initiative are located in rural communities, far from jobs and public transportation. But MassDOT controls a considerable amount of highway land in urban communities, where there's the greatest need for new housing.

In a statement to StreetsblogMASS, a MassDOT spokesperson said that the agency is "always open to speaking with state and municipal officials, developers, and other stakeholders regarding opportunities to support housing and economic development needs on or around our property."

"MassDOT is part of the Administration's integrated initiative to create and foster opportunities to accelerate the production of housing," the spokesperson said. "We strive to support the private development of housing, and to initiate opportunities on our surplus property."

Not in my right-of-way

But several high-profile projects that MassDOT is pursuing around the Boston region, it's hard to find evidence to support the spokesperson's claims.

The agency is currently designing high-profile renovations of several 20th-century expressways in some of the state's most expensive cities.

But even though the agency openly acknowledges these roads are wider than necessary, its current designs in these projects make few, if any, efforts to replace highway lanes with new housing.

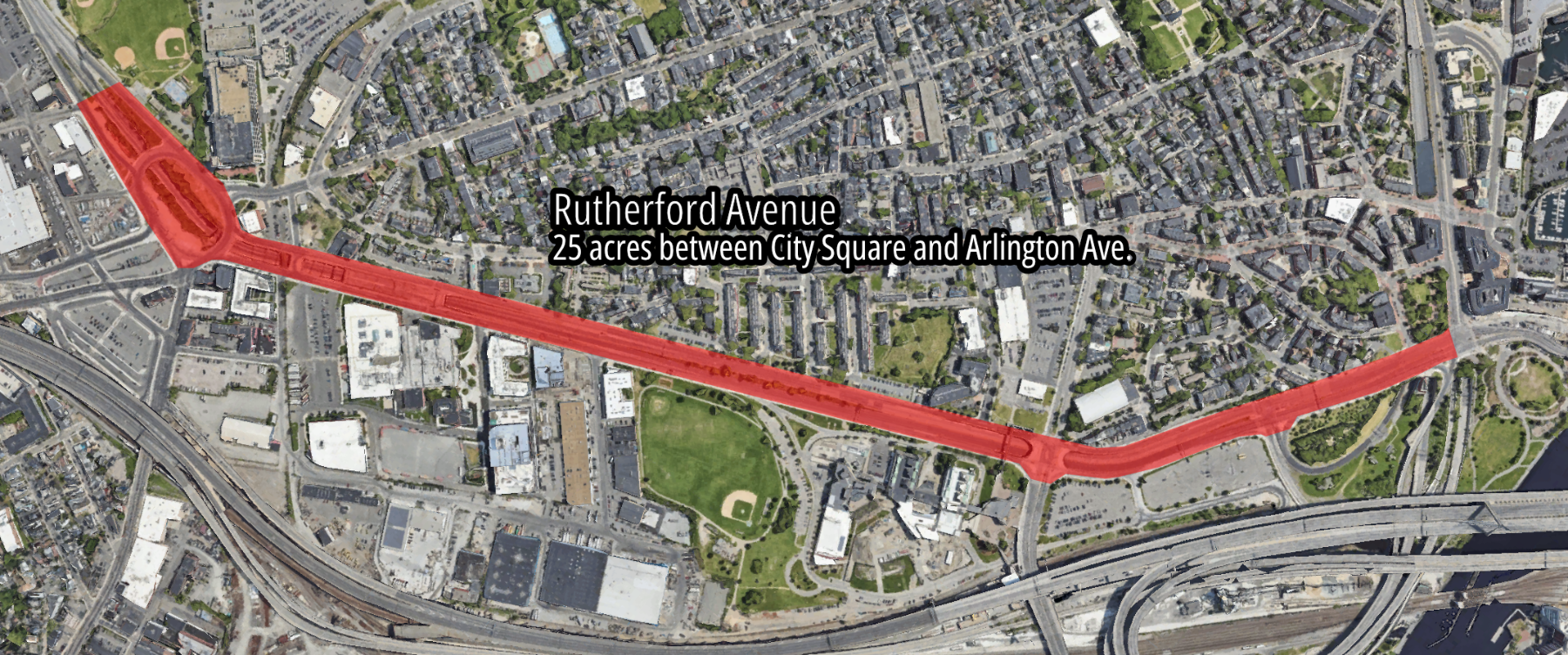

In Somerville, for instance, MassDOT is redesigning the McGrath Highway to remove two redundant traffic lanes through densely populated neighborhoods.

In a February 2024 public hearing for that project, Ryan Kiracofe, then the vice-chair of Somerville's Community Preservation Committee, asked MassDOT officials whether they would make some of the highway's extra right-of-way available for new mixed-use development.

"I'm curious about the newly created spaces that are made from some of the street realignments," said Kiracofe. "They're basically new parcels... How do we ensure that those new spaces are active, comfortable urban spaces? I'm thinking about filling those with programmed park space, but they'd probably be better developed real estate, as housing and retail."

In his response to Kiracofe's question, though, Christopher Cameron, a MassDOT engineer, did not address the possibility of building more housing.

Instead, he talked about landscaping.

"I think we're really focused on adding trees here as much as we can, and green space," said Cameron.

Brad Rawson, Somerville's Director of Mobility, chimed in to address Kiracofe's suggestion more directly.

"When you look at Somerville's four square miles of land area, approximately one square mile of our precious land is taken up by road and rail right of way," said Rawson.

Rawson later added that making room for more housing "is something that we will work on in partnership with the state. So keep asking questions like that, folks."

But at a follow-up meeting in March 2025, MassDOT presented a slightly revised design that eliminated several more redundant turning lanes at several key intersections. But the updated design makes still makes no provisions for new housing development.

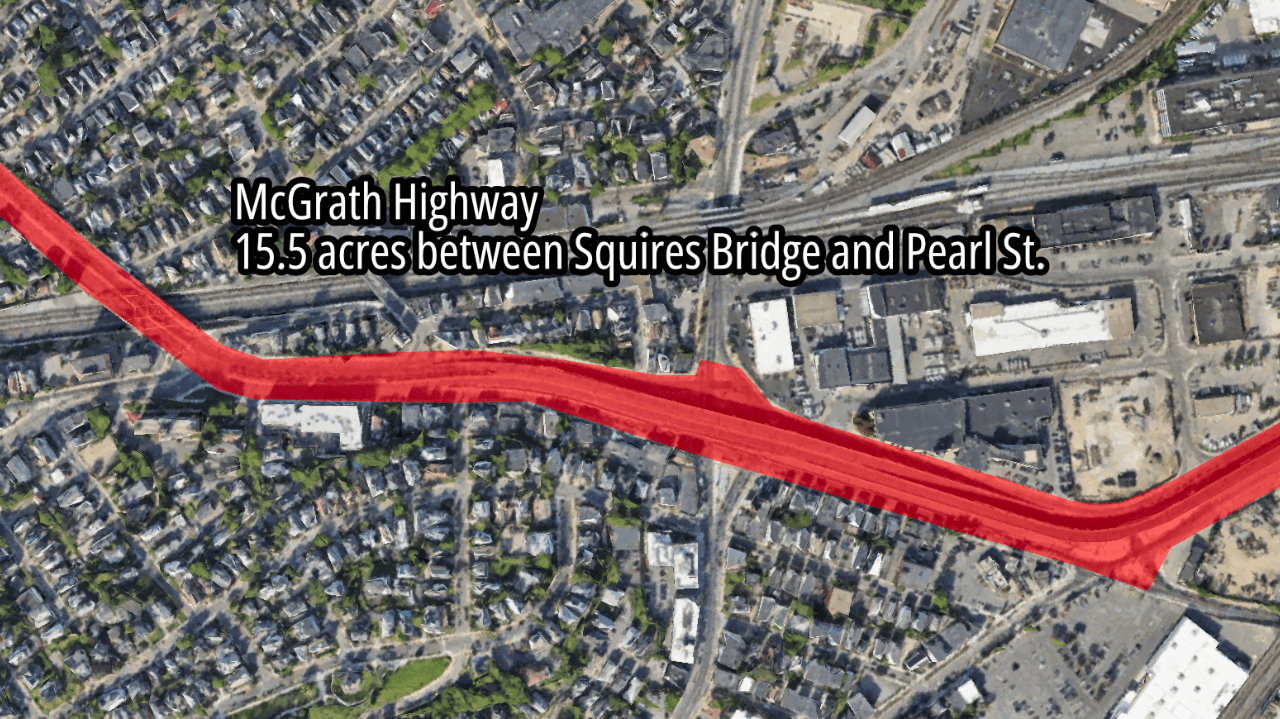

Similarly, a state commission has labored for the past two years to agree on a new, slimmer design for Morrissey Boulevard through Dorchester.

The segment of that roadway near the JFK/UMass Red Line station, between Kosciuszko Circle and Bianculli Boulevard, slices between several large-scale development projects. One proposal proposes seven new high-rise buildings, including 585 new homes, on about 9 acres between Morrissey Boulevard and Interstate 93.

On the other side of the Boulevard, the even bigger Dorchester Bay City proposal calls for almost 2,000 new homes, plus 4.4 million square feet of lab and office space, on 36 acres between Morrissey Boulevard and the ocean.

In between these two projects lies about 20 acres of state-owned land, most of which is paved under 9 to 13 highway lanes.

In a draft study report, published in March, the Commission recommended making Morrissey Boulevard considerably slimmer, with new shared-use paths replacing some of the existing highway lanes.

But the commission – whose members included high-ranking stakeholders from the administrations of Governor Healey and Mayor Wu – appears not to have even considered the possibility of swapping some of the Boulevard's unnecessary pavement for new homes.

"The lack of affordable housing in the Boston Region is a broader problem outside the scope of this effort," the commission asserted.

While Massachusetts waits, other states lead the way

Meanwhile, highway agencies in several neighboring states are proving that highway-to-housing conversions can be successful in revitalizing neighborhoods, increasing local tax revenues, and eliminating the financial and environmental liabilities of obsolete highway infrastructure.

About a decade ago, the City of Rochester, NY and NYSDOT agreed to demolish a 2/3-mile segment of an obsolete inner-city freeway, the Inner Loop, to restore the city's historic street grid and create new parcels for development on the edge of the city's downtown.

In 2023, the city's planning office reported that over 500 new homes had been built on the former interstate right-of-way. A second phase – Inner Loop North – is now ripping down a longer segment of the same highway, and this phase is expected to free up roughly four times as much developable land.

Closer to the Bay State, a realignment of Interstate 195 in Providence opened up more than 26 acres of land at the edge of the city's downtown in 2011.

In the decade since then, a redevelopment commission has helped convert that former highway land into several new parks and more than a dozen development projects, which have built 928 new homes in the district so far.