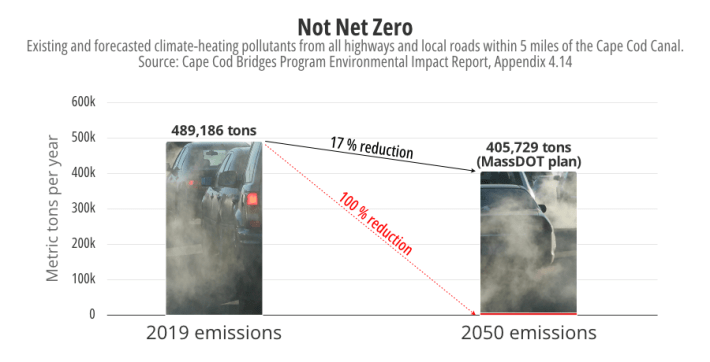

New environmental filings for the Commonwealth's multi-billion dollar Cape Cod bridge replacement project reveal that the state's transportation agency is not planning to meet the pollution-reduction requirements of the state's climate laws.

Last month, MassDOT submitted its long-awaited Environmental Impact Report for the Cape Cod bridges replacement, a multi-billion dollar project to replace the Bourne and Sagamore Bridges over the Cape Cod Canal with new, wider structures that would connect to new highway interchanges on both sides of the canal.

The Massachusetts "Climate Roadmap" law of 2021 requires "all state agencies and regional authorities with jurisdiction over sources of greenhouse gases" to make plans to achieve "net zero" emissions by the year 2050.

That mandate is particularly salient for MassDOT, whose roads and highways are by far the state's biggest – and fastest-growing – source of planet-heating pollutants.

But according to the project's environmental filings, the Cape Cod Bridges and nearby roadways will continue to be shrouded in a thick haze of tailpipe pollution by 2050.

Instead of all but eliminating tailpipe pollution, as the law requires, MassDOT predicts that its roadways within 5 miles of the new bridges will still be producing hundreds of thousands of tons of exhaust gases by 2050.

MassDOT does predict that there would be slightly less air pollution in the region than there is today, but the filings indicate that nearly all of that reduction would be the result of consumers buying new electric vehicles, which the agency expects to happen whether or not its bridge projects proceed.

More traffic for the Cape

Science, policy experts, and the state's official climate plan all agree that MassDOT needs to pursue simultaneously two strategies to accomplish the state's net-zero requirements: electrifying the state's fleet of cars and trucks, while also reducing the total "vehicle miles travelled" (VMT) within the state by shifting more trips to walking, biking, and public transit.

Many transit and roadway safety advocates note that reducing VMT would also mitigate several other serious problems with the state's highway system – like crashes, congestion, and the high costs of vehicle ownership – that electric cars can not solve.

But MassDOT's bureaucracy has consistently lobbied against substantive efforts to reduce driving. In 2024, for instance, the agency's new long-range strategic plan, Beyond Mobility, controversially evaded any committment to comply with the state's official climate plan.

In its environmental filings for the Cape Cod bridge replacement, MassDOT assumes that there will be a whopping 31 percent increase in vehicle miles travelled within the Cape Cod Bridges study area over the next 25 years.

The filings say that their prediction represents "the increase in travel activity resulting from anticipated population and job growth."

But the forecast also reflects the state's lack of plans for new public transit alternatives in the region.

MassDOT expects to spend roughly $2.5 billion on the Sagamore Bridge replacement alone. The project will gobble up roughly one-sixth of the entire state's planned roadway maintenance budget between now and 2030.

Meanwhile, transit agencies like the MBTA still have a multi-billion dollar shortfall for basic state-of-good repair needs, and the state's most transformative plans to reduce highway traffic and emissions with expanded transit service remain unfunded.

Unmitigated

“The state needs to do mitigation. They need to tell us we’re going to take these other steps – like better year-round rail service to the Cape, better buses, ferries – that could reduce traffic and improve quality of life on the Cape," says Clint Richmond, the co-chair of the transportation committee for the Massachusetts Sierra Club.

"But they’re not doing that," he continued. "They’re focused on vehicle infrastructure, instead.”

A spokesperson for the Massachusetts Executive Office for Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA), which is currently reviewing the project's environmental filings, suggested that the state's existing environmental regulations aren't strong enough to require those kinds of mitigation measures from MassDOT.

In an emailed response to questions from StreetsblogMASS, an EEA spokesperson speaking on background explained that "projects must report on mitigation measures if the Environmental Impact Report shows an impact that results from the project."

"MassDEP (the Department of Environmental Protection) does not regulate mobile source emissions from transportation projects," they added.

Too much traffic, too much water

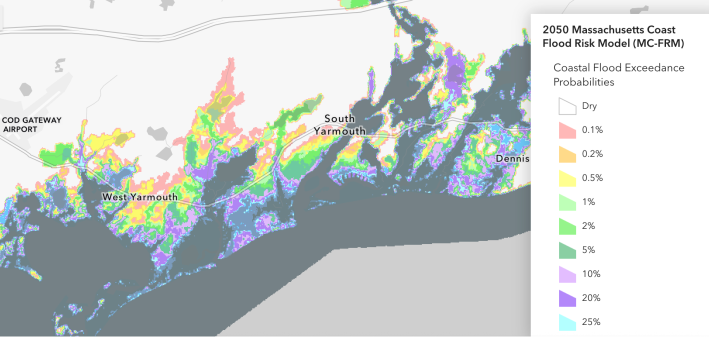

MassDOT's models about the future of Cape Cod traffic in the year 2050 also appear to disregard another important component of climate science: the consequences of sea level rise in coastal communities.

MassDOT's prediction that there will be a 31 percent increase in driving trips over the next 25 years, "from anticipated population and job growth," apparently does not account for the increasing probability that many of the Cape's population and employment centers will be inundated within that timeframe.

According to the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management, many of the Cape's most popular destinations – places like Hyannis village and Yarmouth – will be at high risk of annual flooding by 2050.

Those risks will increase at accelerating rates if major polluters, like MassDOT, fail to eliminate emissions from their highways and smokestacks with sufficient urgency.