This fall, construction crews are making their way through final punchlist tasks on two signature “complete streets” projects for greater Boston: the reconstruction of Commonwealth Avenue through the western Boston University campus, and the reconstruction of Beacon Street along the Somerville-Cambridge city line.

Both projects will open up new protected bike lanes, widened sidewalks, and safer crosswalks for their neighbors.

But these projects share a more dubious distinction: they’ve both been under construction for over three years, and they’ve both missed several deadlines for their completion.

Critics have taken note that both projects share the same general contractor, Newport Construction, based in Nashua, New Hampshire. And because both Beacon Street and Commonwealth Avenue are state roadways, both projects share a common oversight agency – the MassDOT Highways Division.

But such delays and multi-year construction timelines are by no means unusual in Massachusetts. In the Cambridge, for instance, a city-run reconstruction of Western Avenue, built by the D’Allessandro Corporation, broke ground in 2012 and wasn’t finished until 2015, a full year after its originally-scheduled completion date.

An upcoming MassDOT project to rebuild Melnea Cass Boulevard in Roxbury is forecast to be under construction for four years. And a planned reconfiguration of the Massachusetts Turnpike and Soldier’s Field Road through Allston could take a full decade to build.

Some delays in such complex projects may be inevitable. But in a state with serious traffic and transportation challenges, and with millions in taxpayer funds at stake, it’s reasonable for Massachusetts citizens to expect better outcomes.

What happened on Commonwealth Avenue and Beacon Street is worth examining to find ways to improve accountability and keep future projects on tighter schedules. Here’s what we were able to learn.

Commonwealth Avenue

According to MassDOT spokesperson Jacquelyn Goddard, the state’s reconstruction of Commonwealth Avenue in Boston, which started in late 2016, faced two major delays.

First, work in the eastern part of the project area could not be started until August 2018, while contractors from Walsh Construction finished work on a different major MassDOT project, the replacement of the Commonwealth Avenue bridge over I-90 (a project that was also delayed beyond its original timeline).

The second major delay involved the unexpected discovery, after construction had already begun, of an underground duct bank owned by Eversource, the region’s natural gas and electric utility. The duct bank had not been included in the project’s blueprints.

“This is a main distribution line, and was in direct conflict with the mast arm (traffic light structure) at Harry Agganis Way,” according to Goddard. “To move the duct bank would have delayed the entire project over two years.”

Instead, MassDOT decided to work around the duct bank by redesigning that intersection’s traffic light structures. Goddard said that it took the agency a year to design and approve a non-standard structure that would work with the intersection’s many utilities conflicts, and it took another four months to have the custom structure fabricated, delivered and installed.

It’s unclear whether anyone will be held responsible for the omission of the duct bank from the project’s original plans.

“As far as any engineering deficiencies go, MassDOT has a cost recovery process that is chaired by the Chief Engineer that reviews all engineering issues and will make a determination whether cost recovery is justifiable,” wrote Goddard in an email message.

MassDOT did not respond to numerous follow-up inquiries about whether the state was actually following through with that cost recovery process.

By the fall of 2019, the project was largely finished, and the street’s new protected bike lanes were full of people riding between the B.U. Bridge and Packard’s Corner.

But riders were still dodging several metal utility boxes, owned by Eversource, that were obstructing the new bike lanes.

Comm. Ave. #CycleTrack almost complete! Thank you to all the advocates at @bostonbikeunion @MassBike @StreetsBoston @WalkBoston who worked so hard for this. This is Westbound. pic.twitter.com/sUms6x78iL

— Peter Cheung (@bostonaruban) September 30, 2019

In an email at the end of October, Goddard explained that MassDOT was still waiting for Eversource to tie into newly-built electrical connections so that three of its cabinets could be moved out of the cycle track.

“MassDOT provides a monetary incentive to utilities to ensure that they will get the work done in the schedule specified. If they do not, they do not get any of the incentive money,” explained Goddard. “As far as who is accountable when utilities miss deadlines, they are an independent company and therefore accountable to their shareholders who, one would assume, would be rightly upset that their company is forgoing cash incentives.”

StreetsblogMASS reached out to Eversource for its response.

“While a financial incentive is good because it saves money for our customers, our goal is to properly and effectively get our projects done in a safe and timely manner for our employees and customers,” wrote Reid Lamberty, a spokesperson for Eversource, in an email message.

Beacon Street

Eversource’s role was more prominent in Somerville’s Beacon Street project, which also broke ground in 2016 and was originally scheduled to be finished by September 2017.

But by June 2017, according to a report from the Somerville Journal, Eversource had decided to replace its gas main under Beacon Street, thus delaying Newport Construction’s work until the 2018 construction season.

The project attracted more scrutiny earlier this summer, when an Eversource utility pole was found in the middle of the street’s new protected bike lane, and contractors from Newport meticulously painted neon green bike lane markings around it.

“Our utility pole was in place before the bike lane was created. In fact, neither MassDOT nor the City of Somerville had an issue with the pole remaining in the middle of the bike lane,” asserted Lamberty, the Eversource spokesperson. “However, we took it upon ourselves to move the pole out of the bike lane so that bikers would have unobstructed access.”

Blueprints for the project that date from 2015 and are posted on the City of Somerville website clearly show that the pole was to be relocated to the edge of the sidewalk, outside of the new cycle track.

In the same message, Lamberty wrote that in both the Beacon Street and Commonwealth Avenue projects, “multiple utilities (water, gas, electric, sewer, cable) were working in the same area resulting in limited work spaces and opportunities. Additionally, there were times when work we were scheduled to perform was inhibited by improper work by other contractors. Any additional delays would’ve been caused by third-party contractors not associated with (Eversource). We met all of our project deadlines in a timely manner.”

Newport Construction Executive Vice President Richard L. DeFelice was more diplomatic.

“Any professional in this field understands how these things work, and would never cast blame to one individual party in the process,” wrote DeFelice in response to a recent inquiry from StreetsblogMASS (click here to read his full statement, which we’ve reprinted in full as a stand-alone opinion contribution).

“As far as communication improvements, most times these issues are not predictable, and only come to the forefront once the road has been opened up, and inspected," continued DeFelice. “All parties give a concerted effort to do things in the most efficient and responsible way possible.”

Lessons learned

Meeting the region's goals for reducing traffic by encouraging more walking, biking and transit trips will be substantially more difficult if projects like the reconstruction of Commonwealth Avenue – which, at just ¾ of a mile long, represents less than one quarter of one percent of the city’s arterial and collector streets – take three years to finish.

So how can we do this better?

In a 2010 analysis of the Big Dig project for NASA’s ASK Magazine, Boston University professor Virginia Greiman, an expert on large infrastructure projects, advised that the contractors, utility companies, and other government agencies need to share a common goal, and that “incentives must be mutual and built into contracts… to ensure quality, safety, financial soundness, and a commitment to meeting budget and schedule.”

Applying those principles to Beacon Street and Commonwealth Avenue, the incentives for privately-owned utilities like Eversource to finish their own work on time appear to be too weak to be effective.

Both Goddard of MassDOT and Lamberty of Eversource confirmed that the state incentivizes on-time performance by reimbursing the utility for a portion of its construction costs associated with MassDOT projects, but only if it meets project deadlines.

After that, the financial incentive disappears. In other words, at precisely the point in a project schedule where a deadline is missed, and MassDOT needs the utility to complete its work with extra urgency, the cash incentives for Eversource to do so evaporate.

MassDOT also reserves the right to assess damages on a daily basis to its own contractors if work gets delayed beyond the contract's deadline.

But MassDOT will extend those deadlines to account for third-party delays (such as those incurred by Eversource’s work on Beacon Street) and for additional work that gets added beyond the original scope of the contract.

For its own part, Newport Construction appears to have weathered the controversy of building these two high-profile projects.

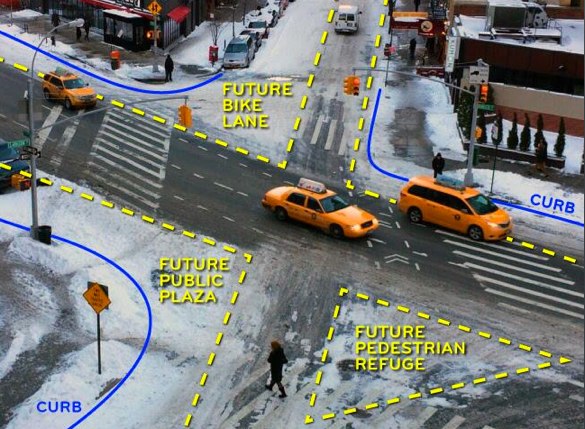

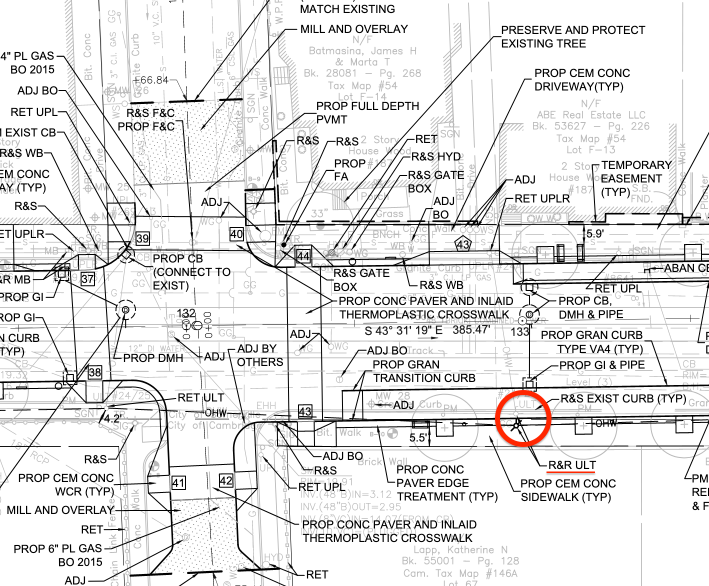

This fall, the firm won another high-profile job: a $7.9 million contract from the City of Cambridge that will create a “protected intersection” at Inman Square, at the corner of Hampshire and Cambridge Streets.

According to project newsletters, city officials anticipate that this project will take 24 months to finish.