The Longwood Medical Area, the densely-packed neighborhood of hospitals and university campuses that lies between Huntington Avenue and the Muddy River in Boston, is one of Boston's biggest transportation destinations: 68,000 people work in the neighborhood (roughly 10 percent of the entire city's workforce) and another 27,000 students are enrolled at one of the neighborhood's educational institutions.

Surveys of the area's workers estimate that 45 percent of them regularly ride a bus, the Green Line, or commuter rail to get to their jobs, and another 17 percent walk or bike (by comparison, in Kendall Square, another fast-growing and arguably more centrally-located neighborhood of research institutions and labs, only 33 percent of workers ride transit, and 15 percent walk or bike).

"As we talk about the importance of transit to this neighborhood, it’s only going to become more important over time," says David Sweeney, the president of the Longwood Collective, a nonprofit that represents the area's hospitals and universities. "The development happening is going to bring more people here, and in many cases it’s replacing parking lots."

But though the Longwood Medical Area (LMA) has grown considerably in recent decades, the transit network that serves the neighborhood hasn't kept up with that growth.

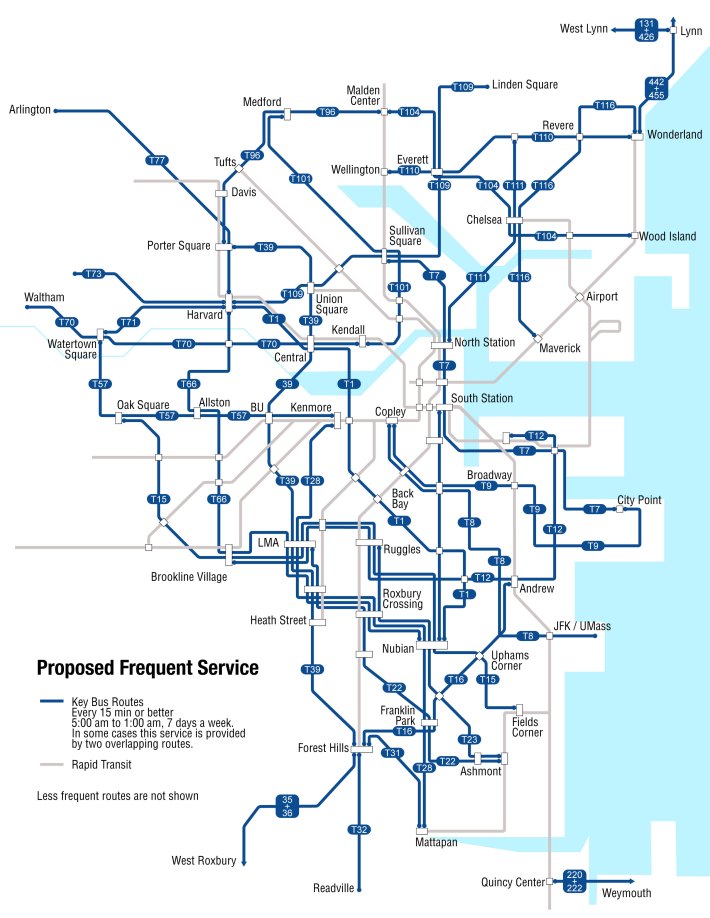

Currently, only two of the T's "key bus routes" – buses that run every 15 minutes or better – serve the southern edge of the LMA along Huntington Avenue (the 39 and the 66). Seven other bus routes serve the core of the LMA on Longwood and Brookline Avenues, but their frequencies are less reliable, and a pre-pandemic City of Boston analysis of bus speeds found that they frequently get stuck in traffic.

The current bus network is also inequitable: in part because the current MBTA bus network lacks direct, high-frequency routes between majority-Black neighborhoods like Mattapan and emerging job centers like the LMA, Black bus riders spend, on average, 64 more hours every year on their commutes than white bus riders.

The T is currently proposing a bus system redesign that aims to address these issues by turning the LMA into a new hub in the region's bus network.

The proposal includes six new "high-frequency" bus lines - with buses that arrive every 15 minutes or less, 20 hours a day - through the heart of the LMA. In addition to bringing more bus service into the neighborhood, including more late-night buses that could serve third-shift workers, the new routes would also make the LMA a major hub in the region's bus network, with new one-seat ride connections to neighborhoods like Allston and Brighton, Ashmont, Fields Corner, Mattapan, the Seaport, Andrew Square, Harvard Square, and Porter Square.

The T is still soliciting feedback on the proposed new bus network, and a major unresolved question is whether the City of Boston will allow dedicated bus lanes and other transit-priority infrastructure on Longwood and Brookline Avenues to ensure that those new bus routes won't get mired in the LMA's notorious congestion.

In a meeting with municipal stakeholders last fall, Caroline Vanasse, then the Manager of Transit Planning at MassDOT, acknowledged that “areas like LMA are currently very challenging to get bus service in and out” and said that "the infrastructure to support these routes is critical."

The Longwood Collective (formerly known as MASCO) which also operates a network of private shuttle buses for the area, recently released a new white paper on the neighborhood's transportation challenges, as well as a new "transportation framework" that aims to balance competing priorities on the neighborhood's congested streets and guide the organization's advocacy for new transportation projects.

"We’ve had dozens of transportation studies done on an ad-hoc basis, but no agreement among the membership about what we’re trying to accomplish. This (framework) gives us a centralized understanding of things," David Sweeney, the group's president, told StreetsblogMASS.

In theory, the framework will let the organization evaluate bus lane proposals according to how well they meet shared principles and values, like safety, convenience, affordability, sustainability, and the prioritization of vulnerable populations and users. It also aims to measure progress in terms of metrics that include transit mode share, crash rates, delay for emergency vehicles, and the percentage of the local street network that includes low-stress bikeways.

But when asked whether his organization would support bus lanes to facilitate the T's proposed service increases, Sweeney demurred.

"It's a tradeoff and it requires analysis," he told StreetsblogMASS. "We don’t have answers, but we have a clear set of metrics that will let us evaluate proposals. We’re bullish about the opportunity here, we just want to make sure it’s done well, in the places where it makes the most sense to happen.”

Many of the LMA's wealthiest doctors, executives, and patients still drive their own private vehicles and expect to find parking in the crowded neighborhood, and in spite of the plan's high-minded principles, their interests are still evident.

For instance, one "action item" in the framework proposes that new transportation proposals should "prioritize access for emergency vehicle access and patients in private vehicles," even though private vehicles are the predominant obstacle that blocks ambulances on the neighborhood's streets.

The framework notably doesn't acknowledge the access needs of patients who come from the 91,500 Boston households - roughly 1 out of every 3 families living in the city - that do not own a car.

In a follow-up email, Sweeney elaborated that "at our core, we try to do everything we can to get everyone who can come here through a mode of transportation other than car to do so, so that patients can come here by car as they need to. Priority access for emergency vehicles could be a benefit of bus lanes but is not automatically one... the project’s success is so dependent on the design details."

Sweeney also revealed that MassDOT and the MBTA are conducting a separate study of bus routes and bus access in the LMA "that will carefully consider the unique, multi-modal needs of our limited road space, and inform the final bus network plans for our neighborhood."

A City of Boston spokesperson confirmed earlier this week that "the City of Boston is working with MassDOT, who is leading a study of the Longwood Medical Area to determine the best bus routing options in this important education and hospital hub... BTD (the Boston Transportation Department) will collaborate closely with MassDOT on this important study to ensure that there is a comprehensive data analysis process and a robust community engagement program."

Related: