For three years now, while workers build a new North Washington Street Bridge over the Charles River between the North End and Charlestown, all bridge traffic – including foot traffic along Boston's famous Freedom Trail – has been confined to a narrow 3-lane "temporary" bridge running just upstream from the construction site.

But work on the new bridge has been on hold for over a year. And the delays are calling into question whether the bridge's original design – which dates to 2018 and lacks dedicated bus infrastructure for Chelsea-bound transit riders – really makes sense for the year 2025, when the new bridge will finally open.

A bus bottleneck

The North Washington Street Bridge carries one of the MBTA's busiest bus routes – the 111 – in addition to the less-frequent 92 and 93 routes through Charlestown.

During peak hours, a bus crawls through the bridge's traffic, on average, every 2 to 3 minutes.

Before the pandemic, the City of Boston estimated that about 17,000 bus riders travel along North Washington Street on a typical weekday.

In September 2019, just before the old North Washington Street Bridge closed for good, the City of Boston painted the curbside southbound lane of North Washington Street red to give southbound buses a clear path from the bridge to their terminal stop at the Haymarket subway station.

In the summer of 2021, the city added a second bus lane in the northbound direction.

But those bus lanes both abruptly end at the traffic signal at Causeway Street, where Chelsea-bound bus drivers must squeeze into a single northbound lane on the temporary bridge that's been carrying traffic since the end of 2019.

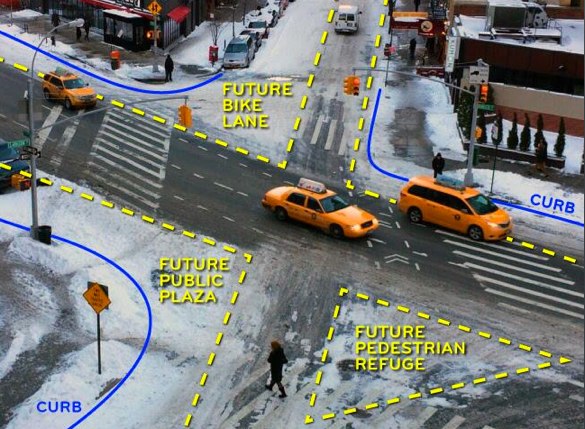

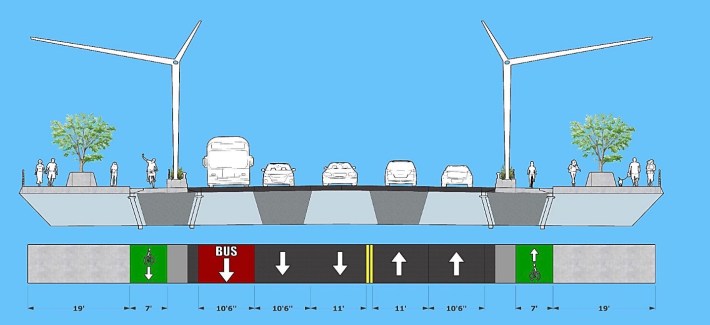

When the new bridge finally opens, sometime in late 2024 or early 2025, it will include wider sidewalks, protected bike lanes, and five lanes for motor vehicles.

Under current plans, only one of those lanes – running only in the southbound direction – would be dedicated for buses:

Learning from Longfellow

The City of Boston's climate plans call for a dramatic reduction in motor vehicle traffic by 2030 – just five years after the new North Washington Street Bridge opens.

In order to meet those goals, streets like North Washington will need to have faster, more reliable bus service to serve more bus riders. And they'll also need to have fewer cars blocking the way.

"We’ve been living with construction for years with only three lanes on a temporary bridge, so why add back another car lane when we have this opportunity?" asked Becca Wolfson, the former executive director of the Boston Cyclists Union, in a phone conversation with StreetsblogMASS last week (note: Wolfson is also a member of the StreetsblogMASS Board of Directors).

We spoke with Wolfson because, in the years since the City of Boston and MassDOT adopted the current design for the new North Washington Street Bridge, she's been involved in successful efforts to reclaim space away from cars on three other Charles River bridges.

In 2018, Wolfson and the BCU delivered a petition with thousands of signatures to MassDOT to urge them to keep a single-lane configuration on the newly-rebuilt Longfellow Bridge in order to make space for protected bike lanes.

The Longfellow Bridge rehabilitation, like the North Washington Bridge project, required several years' worth of disruptive construction work. During that time, motor vehicle traffic on the Longfellow was confined to just one lane, and only in the eastbound direction.

"The past five years have shown one lane inbound on the Longfellow to be perfectly adequate to handle the traffic crossing the bridge," wrote Ari Ofsevit, then an MIT grad student, in an October 2017 email to Wolfson, Stacy Thompson, leader of the LivableStreets Alliance, and Richard Fries, then the executive director of MassBike.

After "several months of stakeholder meetings (with MassDOT) talking about traffic data," Wolfson recalls, the state agreed to install flexible-post bollards to offer some protection for people riding bikes on the eastbound side of the bridge.

In 2019, MassDOT expanded on that pilot by eliminating one of the two eastbound lanes on the western side of the bridge to create more space for the bike lane, while the City of Cambridge got rid of a car lane on its connecting segment of Main Street.

Wolfson said that the experience on Longfellow showed MassDOT that they could carve up car lanes to encourage more bike and transit use without creating a "traffic apocalypse." That, in turn, made it easier for advocates and highway officials to try out similar changes on other bridges.

In 2019, the BCU was part of a coalition that asked MassDOT to try something similar on the Craigie Bridge (also known as the Charles River Dam Road).

And in the fall of 2021, sustainable transportation organizations successfully petitioned MassDOT to remove car lanes to create space for protected bike lanes on the Massachusetts Avenue Bridge over the Charles River – a project that MassDOT officials have since called "extremely effective."

Designed in 2018, delayed 'til late 2024

The 2018 design for the new North Washington Street Bridge already includes wider sidewalks and protected bike lanes.

But in the years since the project began construction, the City of Boston, MassDOT, and the MBTA have all made major new commitments to improving bus service – especially on routes, like the 111, that serve historically under-invested communities of color.

In addition to new bus lanes from the City of Boston that lead right up to the new bridge's entrance, the MBTA is making plans to move even more buses over North Washington Street.

In the MBTA's newly-revised bus network redesign, two proposed "high-frequency" routes will start using the new bridge soon after it opens: the existing 111, plus a proposed new "T7" route that would traverse a new cross-downtown dedicated busway on its route from Sullivan Square to South Boston.

Ofsevit, reached by phone last week, said that painting a pair of center-running bus lanes on the new bridge – ideally with a new stop for the 111 at City Square, to give Chelsea bus riders access to jobs in the Charlestown Navy Yard – would be "a very reasonable ask."

"We have 5 lanes (on the new bridge) and there’s really no need for that many – it seems like an easy win," said Ofsevit. "It’s a really good return on investment, because the investment is basically zero, and the benefit is really, really high."

Ofsevit also noted that while advocates pulled together their campaign for safer bike lanes on the Longfellow Bridge just a few months before the bridge reopened to traffic, recent construction delays on the North Washington project give bus advocates considerably more time to advocate for a dedicated busway.

In September 2021, MassDOT construction inspectors discovered 52 cracked welds at connection points on the new North Washington Street Bridge.

Inspectors also discovered cracks in bridge elements being fabricated at Casco Bay Steel, a subcontractor in Maine.

Figuring out how to repair the steel beams – and resolving disputes over who should be responsible for those repairs – took more than a year, and essentially halted any work on the new bridge's structure.

"If it's not addressed, the steel would have greatly reduced strength, capacity, and structural integrity," said Jim O'Leary, Assistant District Construction Engineer for MassDOT, at an online public information meeting last month. "We caught this early, where these cracks could be repaired before we started placing concrete decks."

The bridge construction contractor is now making detailed repairs to those cracks. Those repairs are expected to be finished in December, after which construction can resume after a 13-month delay.

The switchover of traffic from the "temporary" bridge to the east side of the new bridge, which was originally scheduled to happen in December 2021, will be delayed until December 2023.

Even after that happens, buses and motor vehicles will still share only three lanes of traffic for another year until the temporary bridge is demolished and the western side of the new bridge is completed – a milestone that's currently scheduled for December 2024 (almost two years behind the original schedule).