The Green Line Extension's Medford branch has been open for nearly a year now, but decade-old plans to build hundreds of homes on a city-owned lot next to the new Gilman Square station remain unfulfilled.

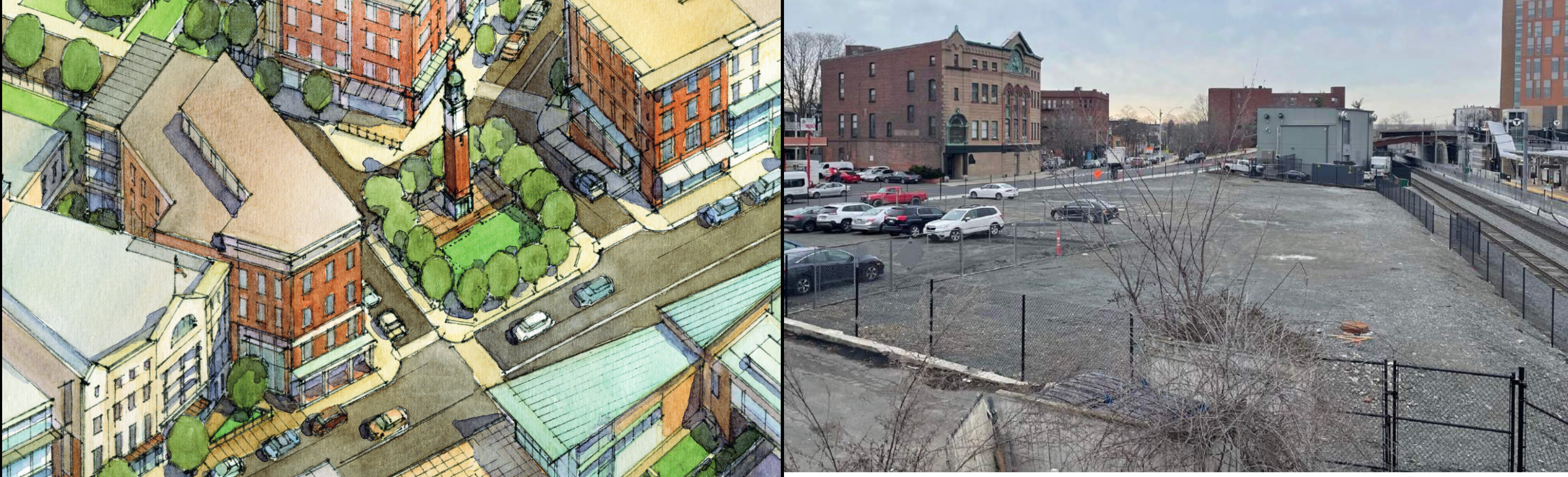

Under the City of Somerville's Gilman Square Station Area Plan, adopted in 2014, various empty lots at the corner of Medford and Pearl Streets were supposed to have been filled with new multi-story buildings and hundreds of new homes by now, in addition to new bike- and pedestrian-friendly streets and civic spaces.

Instead, the "square" is still a fenced-off field of gravel (pictured above) while various city agencies squabble for a stake in the empty land.

At a city council hearing last month, city staff revealed that they want to wait another year to complete a "disposition study" before they decide to do anything with the property.

Christine Carlino, who lives nearby and serves as the board president of the Gilman Square Neighborhood Council, calls the city's lack of resolve "incredibly disappointing."

"The city of Somerville boasts about being one of the most progressive cities in Massachusetts, but this site is an example of how they’re not meeting their goals – for housing, for safe streets, for small businesses – on a site they own and have control over," says Carlino.

Housing plans delayed longer than the Green Line Extension

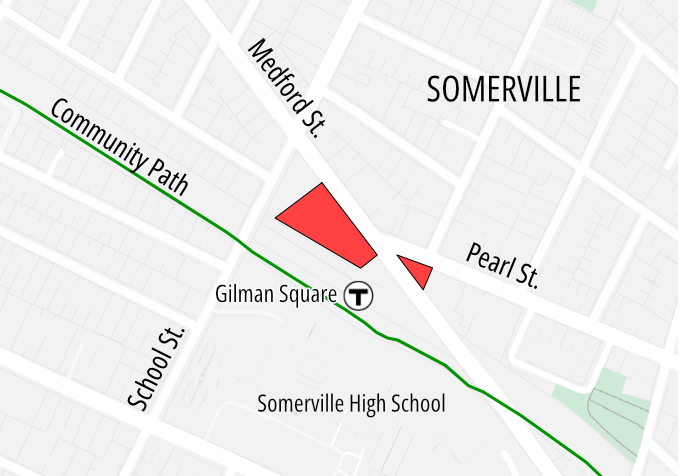

The city owns two key parcels next to the Gilman Square station. The larger of these two – the so-called "Homans site," named for the warehouse building that existed there until Green Line construction demolished it in 2019, occupies 0.8-acres between Medford Street and the new Green Line station.

The city also owns a smaller triangular piece of land in the wedge between Pearl and Medford Streets.

In 2019, the city adopted new zoning rules that legalize multi-story, mixed-use development up to six stories tall with limited off-street parking around Gilman Square.

Many of the site's neighbors consider the empty lots an eyesore, and want to see new development there.

Carlino estimates that the city-owned lots could hold at least 150 homes, a large proportion of which could be designated for lower-income households, plus ground-floor retail spaces for local small businesses.

Further development on nearby privately-owned empty lots could add hundreds of additional homes.

Competing municipal interests stall development

At a City Council meeting earlier this fall, Ward Four Councilor Jesse Clingan asked city staff to explain the holdup.

"It's a huge missed opportunity that we have this space right on a transit node, while the state of Massachusetts is urging communities to build housing around these stations, and right now there's nothing happening down there," said Clingan.

At a November economic development committee meeting, Ben Demers, Economic Development Planner for the City of Somerville, followed up with a presentation on the site's history.

"This is one of the few city-owned lots of this size in this area, and this means that we need to weigh competing priorities for its use," explained Demers.

For instance, city engineers have expressed interest in using the site to build a huge underground stormwater storage tank, to mitigate flooding in the city's aging sewer system.

Demers said that the city has since determined that installing a tank need not hold up redevelopment on the lot, "but it took us a while to get to that determination."

Then, in June 2023, the nearby Winter Hill School abruptly closed after after a chunk of concrete fell in an empty stairwell.

That school's classes have been relocated to temporary sites for the current school year, but some city officials would also like to keep the Homans parcel available for a possible longer-term solution.

"Because of these and other competing priorities, the city will complete a disposition study looking at all city-owned parcels and determining a priority for disposing and selling those sites. We expect that the Homans lot will rank highly," said Demers.

Later in the meeting, Rachel Nadkarni, the city's Director of Economic Development, revealed that the disposition study had not yet been started, and still needed to hire a new planner to manage the project. She estimated it would take another 8 to 12 months to complete.

On that timeline, the city likely won't issue a call for development proposals for the site until 2025, and it would be several additional years before anything actually gets built.

Private development, streetscape projects also on hold

The uncertainty around the city's plans for the center of Gilman Square is also stalling development on privately-owned empty lots nearby, argues Christine Carlino, of the Gilman Square Neighborhood Council.

"Property owners and developers have approached (Gilman Square Neighborhood Council) for conversations, and have expressed hesitation to develop until streetscape designs have been confirmed, curb cut locations are established, and traffic patterns have been established – all of which is being held up by the development of the Homans site. All of these projects are being held up by the city," said Carlino at the November City Council hearing.

The city also has plans to rebuild and reconfigure Pearl and Medford Streets, directing through-traffic onto Pearl and possibly converting the Medford Street bridge over the Green Line into a car-free public space that would connect to the Somerville High School campus.

These plans, as well as a design for a possible new Medford Street entrance to the Green Line station, all hinge on the city making a decision for the Homans site.

Carlino doesn't want any more studies – she says that it's time for Mayor Ballantyne to show leadership and start building.

"The city is spending tax dollars on studies and consultants and all these other things that let them avoid making a decision... It’s a protection mechanism, where they can say ‘we did a study, and the study says this, so don’t blame us.’ Whereas a strong leader would say, 'This is what we need to do,'" Carlino told StreetsblogMASS in a phone call last week.

“Everybody knows we need transit-oriented development and affordable housing, and nobody’s actually making it happen," she added. "It’s going to be hard to convince smaller cities and suburbs to build housing if the City of Somerville won’t do it on its own land.”