This piece originally appeared on "Worcester Sucks & I Love It,” an independent alternative news outlet covering Worcester, Massachusetts. Subscribe at worcestersucks.email

A driver struck and killed a 13-year-old girl on Belmont Street in Worcester on June 27.

The teenager, identified as Gianna Rose Simoncini, was attempting to cross Belmont Street between Plantation Street and Lake Avenue, a six-lane artery sandwiched in the middle of a residential neighborhood and UMass Memorial Medical Center.

Gianna’s death comes at the tail-end of an often embarrassing campaign to undo the traffic-calming redesign of Mill Street, and just in time for the debate over lowering the city-wide speed limit to 25 miles per hour.

Gianna’s father, Jose Diaz, described the incalculable loss via a message on GoFundMe:

“Gianna was more than just my daughter; she was a bright light in our lives, a source of joy, and a soul full of dreams. Her sudden departure has left us devastated and grappling with emotions beyond words.”

We typically think of these kinds of incidents as unavoidable tragedies, but let’s call them what they are: Murders. Gianna Rose Simoncini was killed as a part of a vast conspiracy that has resulted in the premeditated murder of thousands. Planners, engineers, and politicians designed a system of roads that, for the sake of cars, made pedestrian deaths permissible. This kind of capricious negligence has a name: social murder (more on that later).

Belmont Street is a road designed to kill, mixing a high-speed, multi-lane traffic artery with a local access street. It’s a six lane monster cutting through the heart of the city, designed to get residents to and from Trader Joes, Whole Foods, and other Shrewsbury businesses as quickly as possible.

The term for these kinds of thoroughfares is stroad: not quite a street, not quite a road. Stroads are often noted for their high speed limits and lack of safety features, such as traffic calming measures, adequate street lighting, and crosswalks.

In a tweet, Bill Shaner was quick to point out the half-mile distance between crosswalks where Gianna died:

According to the Governor’s Highway Safety Association (GHSA), over 60 percent of pedestrian fatalities occur on stroads, due in part to the speed of traffic that they encourage. As a car’s speed increases, it becomes exponentially more deadly.

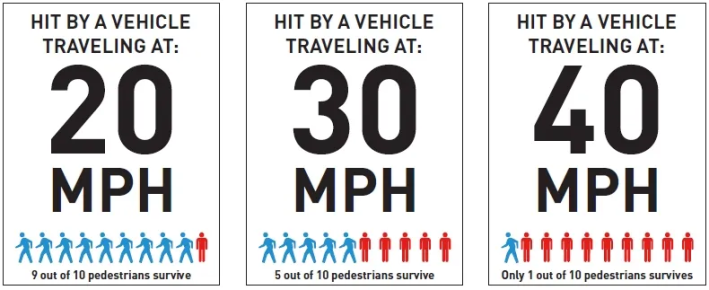

The speed limit on Belmont Street east of Lincoln is between 30 and 35 miles per hour, with travel at 40+ miles per hour being common. When a pedestrian is hit at 20 miles per hour, they have a 90 percent survival rate, meaning 1 in 10 will die.

Increase to 30 miles per hour, and the chance of survival is a coin flip: 50 percent survive, 50 percent die. When increasing speed to 40 miles per hour, the results are grim: only 1 in 10 pedestrians survive crashes at that speed, or a fatality rate of 90 percent.

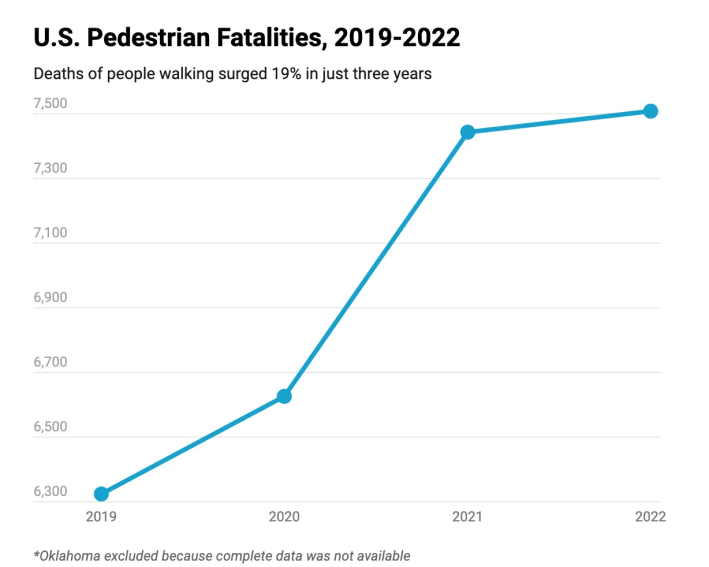

Our infrastructure is designed to prioritize cars above everything else. As a result of decades of building roads for faster and denser car traffic, pedestrian fatalities have reached an all-time high. According to NPR, “every day, 20 people walk outside and end up killed by a moving vehicle.” The GHSA reports that 7,508 pedestrians were killed in traffic accidents in 2022, the highest number since 1981:

Those who are too young or too poor to drive risk their lives every time they leave the house. In Massachusetts alone, the fatality rate was 1.43 pedestrian deaths per 100,000 people in 2022. For comparison, the homicide rate in Massachusetts, which includes vehicular manslaughter, is 2.5 deaths per 100,000 people.

Knowing what we know about public infrastructure, the only reasonable conclusion is that 13-year old Gianna wasn’t just killed, she was murdered.

While the driver certainly did not premeditate, nor have motive, we can easily identify those responsible: the politicians and residents, past and present, who demand that we prioritize car travel at the expense of all others, and fight tooth and nail against even modest improvements to public safety. Even before cars were invented, this phenomenon was named and shamed by Friedrich Engels in his 1845 book The Condition of the Working Class in England:

“When one individual inflicts bodily injury upon another such that death results, we call the deed manslaughter; when the assailant knew in advance that the injury would be fatal, we call his deed murder. But when society places hundreds of proletarians in such a position that they inevitably meet a too early and an unnatural death, one which is quite as much a death by violence as that by the sword or bullet; when it deprives thousands of the necessaries of life, places them under conditions in which they cannot live – forces them, through the strong arm of the law, to remain in such conditions until that death ensues which is the inevitable consequence – knows that these thousands of victims must perish, and yet permits these conditions to remain, its deed is murder just as surely as the deed of the single individual.”

At the time, Engels was referring to the trappings of the industrial revolution: exploitative and unsafe workplaces, horrific living conditions, lack of health care, and other material conditions of the 19th century working class, problems that persist to this day. Social murder, unlike more traditional forms of homicide, is a crime of the political elite against the poorest and most vulnerable in our society. Social murder is the culmination of years of systemic neglect, thousands of intentional choices compounding to produce horrific outcomes. Pedestrian deaths aren’t just unfortunate realities, they are the result of intentional choices made at the local, state, and federal level.

In Worcester, even a modest redesign to calm traffic can provoke fierce pushback from residents and city politicians. The Mill Street redesign was a key point of contention raised by Jose Rivera, who mounted a failed campaign to unseat city councilor Etel Haxhiaj’s in last year’s election.

During a council meeting on Mill Street, Donna Colorio embarrassed herself by attempting to mischaracterize crash data for Mill Street, all but asking the city manager and Worcester police to fabricate data to agree with her conclusion that the redesign is dangerous (it’s not).

Moe Bergman has pitched an expensive project to undo the traffic calming measures and to give city council veto powers over future road redesigns. Bergman’s proposal was dashed after a wave of public support for more inclusive streets, but the fight’s not over: Public hearings are about to be held about a similar revamp of Chandler Street, another busy and dangerous artery through the city.

City council is also considering lowering the citywide speed limit from 30 to 25 miles per hour, a measure Boston implemented in 2017. In Boston, the change produced a 29 percent drop in driving over 35 miles per hour, speeds we know are particularly fatal to pedestrians.

When we build six-lane highways in the middle of dense neighborhoods, people die. When we cheap out on traffic-calming measures, people die. When we fight, roll back, or sandbag infrastructure improvements to make pedestrians safer, people will die. We can’t just brush off these deaths as the unfortunate cost of living in a modern society.

The city of Worcester has an opportunity to save lives by making smarter, data-driven decisions as we redesign our transit infrastructure. Credit where it’s due, city hall is trying. The Department of Transportation & Mobility is executing on a pedestrian safety initiative called Vision Zero, and City Manager Eric Batista has signaled commitment to the issue. He frequently and pointedly uses the term “traffic violence,” identifying it as a core issue of his administration. But, as discussed, these initiatives are endangered by pushback from the city council.

If the resistance to traffic calming measures is successful, blood will be on the hands of those that fought it, especially councilors Bergman, Colorio, King, and Mero-Carlson. As the debate rages on for safer streets in Worcester, we must ask ourselves: Is shaving a few minutes off of your commute worth murdering children in cold blood?

If you’d like to make a difference and support lower speed limits across the city, you can fill out this City of Worcester public survey. Information about the Chandler Street redesign and how to get involved can be found here. You can support Gianna’s family by giving to their GoFundMe.

Greg Opperman is a software engineer and former newsroom developer at the Boston Globe. His past writing for Worcester Sucks includes pieces on Mill Street and the 2023 municipal election results. Follow him on Twitter @gopperman.