Nathan Fontes-Fried of Swampscott had been living with a sense of dread all summer as he waited for the Massachusetts Registry of Motor Vehicles (RMV) to revoke the title and registration on his company truck.

Liveried in a sky blue with a white right whale woodcut as part of its “Nate Photography” logo, the tiny truck had been serving well as both a practical work vehicle and rolling billboard.

A photographer, woodworker, and avid fisherman, Fontes-Fried isn’t much of a car guy – he couldn't even drive a stick when he took delivery of the manual-transmission Honda Acty a year earlier. But he had invested some $8,000 on the Japanese import, and the RMV was threatening to turn it into an albatross.

On June 18, the RMV announced a ban on Japanese kei trucks, including Honda's Acty and nearly identical models from Mazda, Mitsubishi, Subaru, Suzuki, and Toyota.

The American Standard

“The National Highway Traffic and Safety Administration,” the Registry claimed, “does not endorse the use of these vehicles on public highways because they do not meet federal motor vehicle safety standards.”

In fact, the federal government is perfectly okay with importing, selling, and driving these vehicles on American roads as long as they are at least 25 years old. But the RMV, relying on a thinly researched 2011 policy paper from by the American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators (AAMVA), went ahead with its ban.

The AAMVA's chief complaint about kei trucks was that they "were not designed to meet North American vehicle safety standards and don't meet current emission standards."

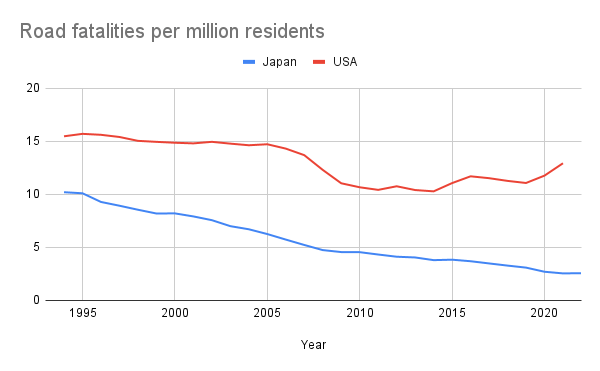

However, kei trucks have always been subject to Japanese safety and emissions regulations; since 1998, they've also been subject to European Union rules, and they're considerably more fuel-efficient than most vehicles. Both the E.U. and Japan have dramatically lower death rates from roadway violence than the United States.

Chaos ensued, with owners of all manner of Japanese imports sharing RMV rejection letters on social media.

The RMV refused to register Peter Ferraro's Nissan Skyline – a sporty sedan the size of a Toyota Corolla. Raymond Moy, who had been a leading advocate in the movement to overturn the ban, documented his troubles getting any of his several Japanese imported vehicles registered.

Moy joined other enthusiasts to lobby elected officials and organize opposition to the ban. More than 900 people joined a Facebook advocacy group and dozens testified at two meetings of the MassDOT Board of Directors over the summer.

On September 18, the RMV issued a reprieve, allowing kei trucks to be registered while pledging to further study their safety.

Regulators and blind spots

We still don't know what went on behind the scenes, but from the testimony and media coverage, it emerged that kei trucks appeal not only to aficionados and vintage car enthusiasts, but also to practicality-minded motorists.

At 1,500 pounds, well under $10,000 (solid examples can be had for $5,000 or less), and a maximum of 11 feet in length, the kei truck provides much of the capability at a fraction of the weight, size, and cost of a full-sized truck.

Repair shop Precision Motorwerks in Marblehead purchased a kei truck in 2020 to replace its dying Ford Ranger pickup for dump runs. Alex Perkins, a mechanic at Precision, praises its practicality, the abundance of tie downs to secure a load, and its easy serviceability. A motorcyclist – he was wearing his riding clothes when we spoke at the shop – he told me he feels more than safe enough behind the wheel of the kei truck. Pointing to a customer's Chevrolet Suburban parked nearby, he added that around town he feels better in the tiny Japanese alternative.

“When you want to park the Suburban,” he observed, “it's 'Where do I put the anchor?' The visibility is poor. With this, I park within an inch of where I want to be.”

Moy, who uses a Cadillac Escalade on long family trips and for towing his kei vehicles, agrees.

“In the kei truck you're sitting at the proper height,” he says. “I don't feel any less safe than in a car.”

But his Escalade has a 16-foot front blind spot because of its long, high hood.

“It's safe for me inside the car, but is it safe for people around me?” asks Moy. “Probably not.”

The state and federal governments have done extensive research on the growing blind spots on large SUVs and pickup trucks – hazards that are especially deadly to children.

Meanwhile, with each passing year, 25-year-old kei trucks become safer, more fuel-efficient, and attractive; air bags and crumple zones were added in 1999. According to Automotive News, imports of 25-year-old vehicles will have grown from fewer than 300 in 2010 to some 20,000 in 2024, with Japanese imports leading the way.

Where the issue has come to a head, as in Massachusetts and Texas, common sense has prevailed. Immediately following the RMV reversal, state representative Steven Howitt of Bristol filed a bill to legalize kei vehicles once and for all. Yet they remain banned in most New England states.

The tempest over kei trucks reflects an approach to regulations that has prioritized safety for people inside motor vehicles at the expense of safety for everyone else.

But as the fleet of heavy EVs expands and pickup trucks and SUVs continue to bloat, awareness of the threat posed by excessively heavy vehicles is becoming too intense for governments to ignore any longer. Earlier this month, NHTSA proposed its first pedestrian protection standards, a significant shift.

These cheerful little pickup truck alternatives may someday become as common as e-bikes and electric scooters have become over the last several years. At that point Nate Photography may need to find a more unique rolling billboard.