The City of Boston has 8 years to cut the volume of citywide car traffic roughly in half by replacing millions of car trips with walking, biking, or transit trips in order to meet its climate goals.

But when it comes to designing safer streets to make that future a reality, the city is binding itself with assumptions that it won't actually meet that target, and sacrificing public space that could otherwise be dedicated to bus lanes or protected bike lanes in order to accommodate pre-pandemic volumes of motor vehicle traffic.

The tension between accommodating 20th-century volumes of car traffic and creating a city that stands a fighting chance of meeting its climate goals is evident in many public works projects, but it's especially salient on Cambridge Street, a critical bike route between downtown Boston and the Longfellow Bridge to Kendall Square in Cambridge.

Even in its current condition, without any dedicated bike lanes, between 14 and 17 percent of all vehicles on Cambridge Street are bikes in the morning and evening rush hours, according to City of Boston bike counts.

The GoBoston 2030 transportation plan identifies Cambridge Street as a high-priority corridor for better bike facilities, and the street was also included in the city’s pre-pandemic planning for the ‘Connect Downtown’ bike network.

The city also names Cambridge Street, in its current form, as a serious safety hazard; it ranks among the top 3 percent of the city's streets for injury-causing crashes involving people riding bikes. On May 29 of this year, a driver struck and killed a pedestrian on Cambridge Street near Blossom Street, according to MassDOT's crash database.

In spite of those urgencies, earlier this year, the city published a detailed website that outlined a variety of design constraints that allegedly prevent them from reducing the number of motor vehicle lanes and installing continuous protected bike lanes on both sides of Cambridge Street.

Some of those constraints are technical, like a code requirement to retain at least 20 feet of "clear width" between curbs or bollards for emergency vehicle access; others are self-imposed, like a desire to avoid moving curbs on Cambridge Street's wide median islands, and a desire to retain loading zones in front of businesses on some blocks.

But some of the city's design constraints are a mixture of political and technical: namely, the decision to accommodate pre-pandemic volumes of vehicular traffic on Cambridge Street, in contradiction of the city's GoBoston 2030 mode shift goals.

"Most intersections on Cambridge Street have a lot of left-turning vehicles. That means we have to give them their own dedicated time to move. And, we can't have them moving at the same time as an oncoming protected bike lane. Some intersections on Cambridge Street also have too many right-turning vehicles to allow them to move at the same time as a protected bike lane," according to the city's website.

"Because of these space constraints, and the need to maintain vehicle capacity at certain intersections, certain types of bike facilities may not be possible now," the city concludes.

On the Cambridge side of the Longfellow Bridge, where Cambridge Street becomes Main Street, the City of Cambridge has eliminated two motor vehicle lanes in recent years and replaced them with new protected bike lanes to help accommodate booming growth of new labs and office buildings in the surrounding Kendall Square neighborhood.

StreetsblogMASS asked the City of Boston's Transportation Department why it would design for a future of sustained pre-pandemic traffic congestion on Cambridge Street, when that assumption clearly contradicts the city's climate and transportation goals.

"The reason we look at existing traffic volumes is to design an appropriate, safe connection for people on bikes, not to use forecasted volumes to dictate our design choices," a Boston Transportation Department official responded. "For example, we use NACTO and MassDOT guidance on maximum numbers of conflicting vehicular turns over a separated bike lane. This is a real number, not a theoretical future number. We do not design bike facilities that are dangerous on day one, and instead study conditions to ensure safe, effective street design."

However, advocates worry that the city is asking bicycle users and pedestrians to endure an even less safe status quo.

"At least 8 people riding a bike have been seriously injured on Cambridge or Charles Streets in the past two years.* That’s not a theoretical number, either," Becca Wolfson, executive director of the Boston Cyclists Union, told StreetsblogMASS in a phone call last week (editor's note: Wolfson also serves on the StreetsblogMASS board of directors; see also the note on the crash data below). "Vulnerable road users are being hurt, and this street is dangerous right now."

The city's recommended "quick-build" design for Cambridge Street proposes a single flexpost-protected bike lane on the westbound side only. One block near the West End Library would feature a paint-only bike lane, and in the approach to the intersection of Staniford Street, bikes and right-turning motor vehicles would be expected to share a lane.

The proposal makes no provisions for bike lanes on the eastbound side of Cambridge Street, where there are more competing demands for curbside uses like outdoor dining and loading zones.

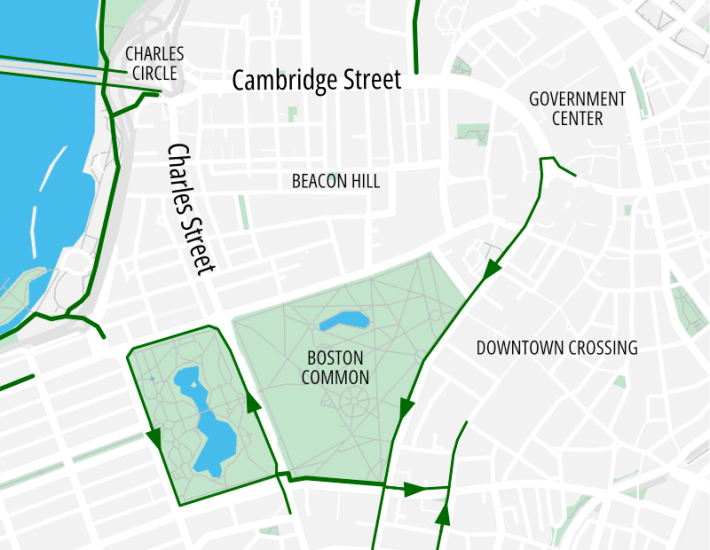

That eastbound gap could be mitigated by a new protected bike lane on Charles Street, which isn't a parallel route but would provide an attractive bikeway from the Longfellow Bridge to downtown Boston via the new bikeways around the Boston Common and Public Garden.

However, proposals to add safe bike facilities on Charles Street through Beacon Hill, where nearly one out of every three vehicles on Charles Street is a bicycle, according to official city traffic counts, have languished thanks to objections from a small group of wealthy Beacon Hill home and business owners, as we reported last year.

On Tuesday morning, the Boston Cyclists Union will stage a people-protected bike lane on Charles Street "to demonstrate that space on our roads can and must be redistributed so people on all modes have access to the street."

"We know the city has made commitments to closing the gap between the downtown bike network and the Longfellow Bridge. People in city leadership have said that the downtown network doesn’t work without a connection to Charles Circle," says Wolfson of the Boston Cyclist's Union. "So we’re asking for the city to follow through for the outbound lane on Cambridge Street this year, plus a quick-build bikeway on Charles Street this year, as soon as possible."

* A note on the crash data: There are discrepancies between the City of Boston's crash data, which indicate that there have been 13 crashes involving a bike on Cambridge Street since the start of 2018, and the MassDOT IMPACT crash database, which indicates there have been 9 crashes involving either a bike or a pedestrian in the same period.